(Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Museum Purchase; 1988.39)

“… last night I took A. into my arms, and found her lips were waiting mine…”[1]

Note: Unless stated otherwise, all photographs and archival materials illustrated in this post are currently owned, or were owned in the past, by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc. All photographs by Edward Weston © Center for Creative Photography [CCP], University of Arizona.

A SERENDIPITOUS REVEAL

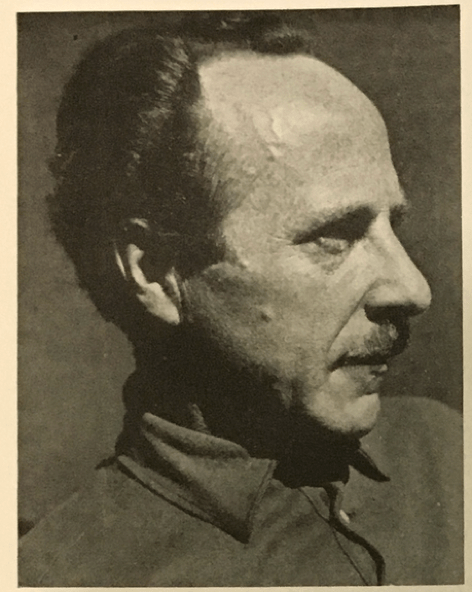

Edward Weston is legendary for his numerous love affairs—some brief, others relatively enduring. Never happy in his first marriage to Flora Chandler, Weston enjoyed lengthy relationships with Margrethe Mather, Tina Modotti, Sonya Noskowiak, and Charis Wilson—arguably THE love of his life—whom he married in 1939. Weston mentions these women openly in his Daybooks, which overflow with detailed accounts of family, social, artistic and professional experiences. But the journals are also peppered with startling, deeply personal, sexually charged revelations. In a bid to discretion, Weston rarely identifies his other lovers by name, only by initial, leaving today’s readers in a state of frustrated curiosity.

One of the more intriguing of these mystery lovers is “A,” whose presence dominates Weston’s Daybooks from October to December 1928 during his sojourn in San Francisco. This youthful beauty with “chestnut eyes,”[2] about whom Weston writes with such ardor and frequency, was clearly one of his great passions. I wondered who she might be, but harbored little hope of unravelling the nearly century-old secret. Then, through a serendipitous acquaintance made during a vacation in 2022, the enigmatic “A” was unexpectedly revealed.[3]

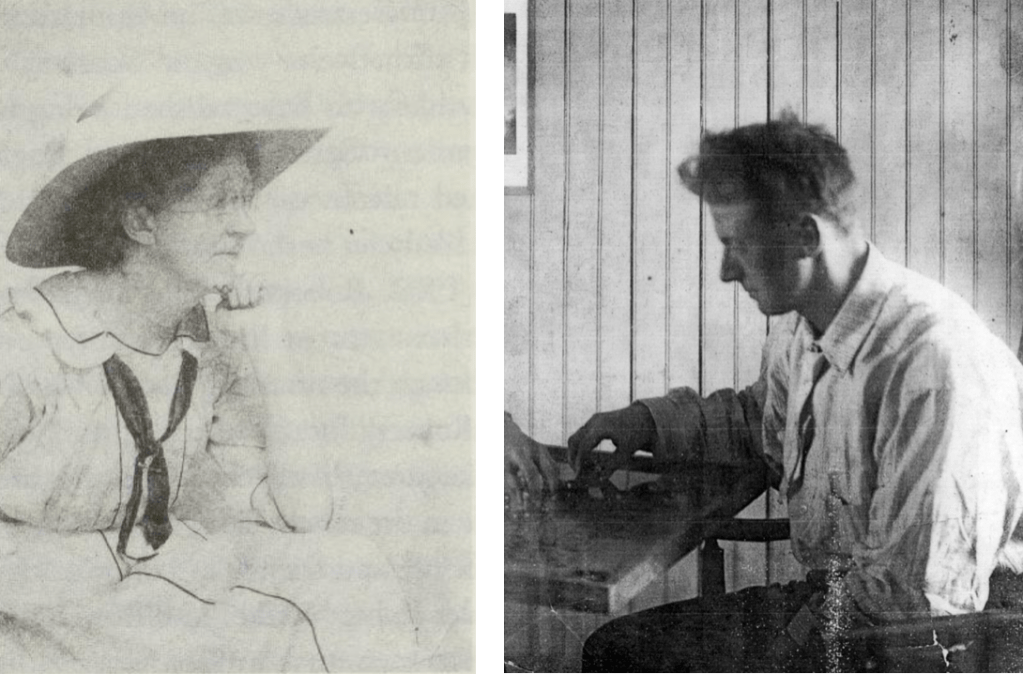

She is Amaryllis Nicol (1905–1987), the younger sister of Margaret Nicol (1903–1983)—another of Weston’s San Francisco sirens—two progressive offspring of a quintessentially bohemian family. Their connection with Weston would prove fleeting but intense.

SAN FRANCISCO 1928

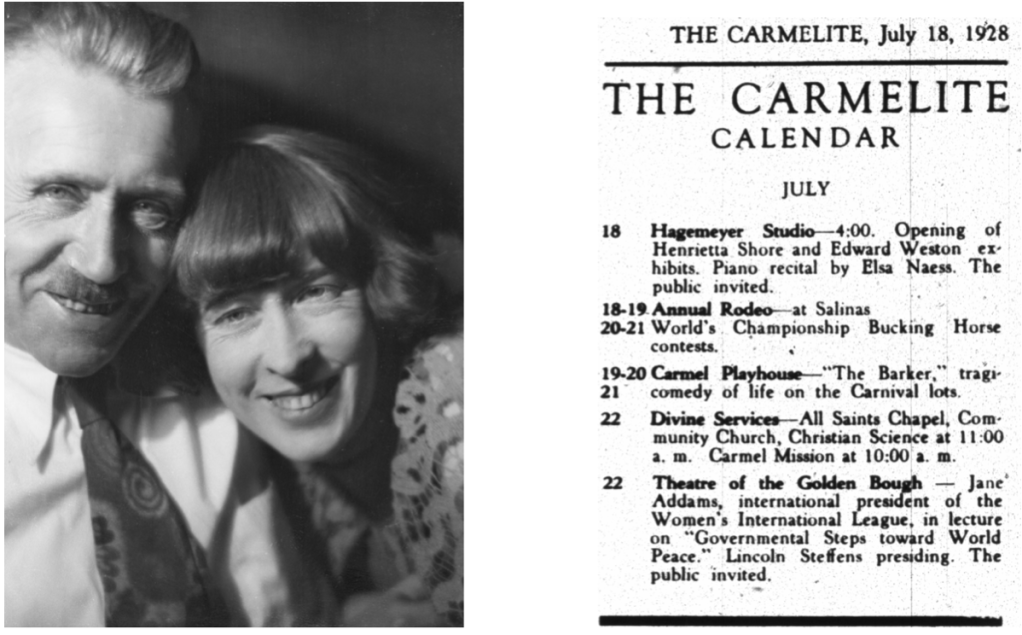

In July 1928, Weston made a temporary trip up the coast from Glendale to be on hand for two exhibitions of his work. The first, at San Francisco’s East West Gallery from July 1–22, included photographs by his son Brett; the second, at the Carmel studio of Weston’s friend and fellow photographer, Johan Hagemeyer, opened on July 18th in conjunction with paintings by Henrietta Shore.[4] In late August, Edward and Brett made a more permanent move to San Francisco, taking up residence in Hagemeyer’s Union Street apartment—a most convenient arrangement as Johan would be in Carmel until October.[5] On August 24th, Weston reminisced about his 1925 stay in this same light-filled location and penned these thoughts upon starting the new adventure:

2682 Union St. Three years ago or more I sat under this same skylight, with morning coffee,—gazing out over the bay,—writing, dreaming. In those days my writing was mostly in letters to Tina [Modotti]! Romantic days! / How very strange to be here once again: the same sirens warning the same ferry boats, the same fog drifting over to shroud the bay and obliterate the horizon. I loved this place. I sought it again,—and it was empty awaiting me. / Months have been crowded into weeks since leaving Glendale. I hesitated for long before deciding that I should be here during my exhibit [East West Gallery]: until the day before leaving I had not definitely made up my mind. Yet is that literally true? For all the while I knew I should and would make the trip. / … / Somehow I felt a change from Glendale was in order, that something was about to happen.[6]

(Photograph on Zillow Real Estate listing, 2023)

Professional and artistic advancement were the primary motives for Weston’s move to San Francisco, as was relief from an increasingly oppressive family atmosphere in Glendale. With fresh independence came an additional benefit: opportunities for unfettered gatherings replete with exuberant dancing—a type of socializing Weston had long enjoyed. It was at one such party that a seductive gambol with Margaret Nicol inspired his first Daybook entry about her:

Sunday morning, [probably 16 September 1928]: It was a jolly party at Margaret Nicol’s,—only nine of us. I took Elsa [Naess] and Ida [unidentified], or we did, for Brett drove. Walt Kuhn, painter, here from New York, … The episode of the evening for me was a dance with Margaret Nicol,—she a professional dancer. I can easily call it one of the dances of my life. We were both well “lit.” I put on “La Pintura Blanca.” It was perfect for both of us. Reservations were cast aside: I had heretofore made no gesture because of her lover. The dance became wilder, a mad whirl, kissing, biting, mauling,—ending by a crash to the floor with the last note, where we lay unable to move. / I needed just such such an evening—a release from my sordid grind. I went hoping to become gayly borrachito, [lightly drunk], not drunk. / No matter, I shall have pleasant memories. / Brett and the girls got me home. Never have I been so helpless before. Elsa swears I mixed drinks. I think not. I was depleted when I went there, and the bartender was too attentive.[7]

How Weston arrived in Margaret’s social orbit is unclear—possibly via the Norwegian pianist and dancer Elsa Naess who Weston likely met through Hagemeyer. Indeed, Hagemeyer and Naess enjoyed a close personal and professional relationship. He photographed her numerous times beginning in 1928 and she performed at his Carmel studio on July 18th—the same day the Weston and Shore exhibitions opened there.[8] Apparently, Johann and Elsa also shared a studio and/or a residence, as reflected in this 1929 San Francisco City Directory listing: “Hagemeyer Johan (Elsa N) photog 177 Post R404 r2929 Scott.”.[9]

(Johan Hagemeyer Photographs, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, BANC PIC 1964.063)

Right: “Events at the Hagemeyer Studio,” The Carmelite, 18 July 1928, p. 2.

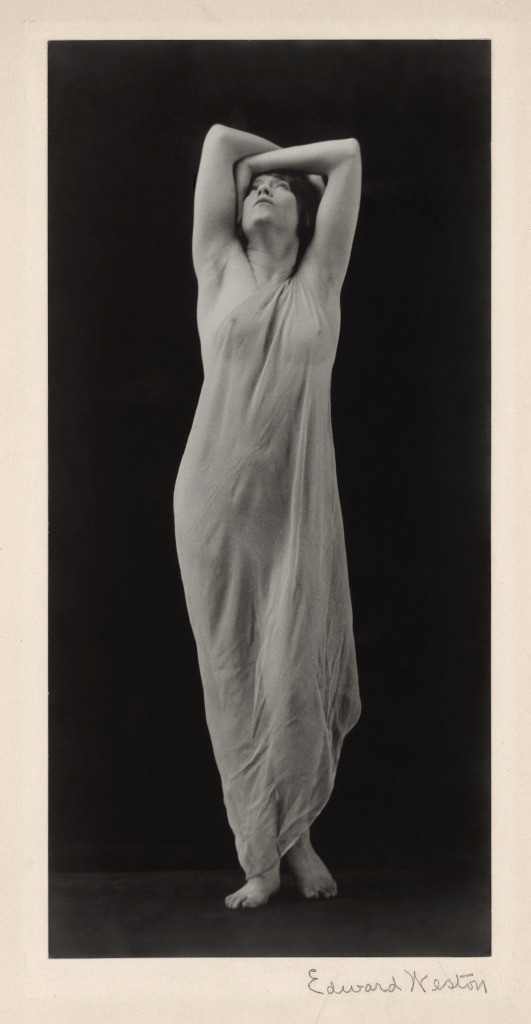

Weston may (or may not) have demurred from a sexual relationship with Margaret Nicol but, captivated by her talent and beauty, he wasted no time in arranging a studio session. On October 4th he wrote: “I have an appointment for a sitting with Margaret Nicol at 10:00, at my request and expense. Why I invited her is yet to be seen.”[10] Fortunately, Weston’s instincts proved correct, for the next day he rhapsodized: “As I worked with Nicol, the tightness in my head vanished. Music and dancing!—The excitement of capturing evanescent gestures!—I became one with the transient moment and worked en rapport.”[11] Weston’s comment provides a compelling insight into his creative approach. Unlike commercial sittings, this was an intimate collaboration between two artists discovering mutual inspiration in an unrestrained atmosphere enhanced by music and dance. Weston extolled this fruitful experience on October 6th:

A great deal was accomplished: the darkroom ready for work. Brett developed three dozen negatives of Margaret Nicol,—he does most of my developing now, and does it well. / A staged dance may be artificial, and this dance before my camera could be called staged. But she well forgot the camera, and the negatives show spontaneity. There are a number that I may use for myself,—better things than one usually sees of the kind,—rhythmical, feelingful. Technically, they are extraordinarily uniform in excellence, sharp and well timed: 1/5 second exposures at f/4.5 with new Dupont panchros, which are faster than E.K. Co. They are more likely to have imperfections though.[12]

(Courtesy of Georges Rey and Cynthia Haggard)

The “feelingful” Margaret had been dancing since childhood and took her vocation seriously. In late 1919, while living with her family in Mill Valley, California[13] (just north of San Francisco in Marin County), the self-assured and enterprising teenager sought to establish a dance class for children:

Miss Margaret Nicol, if guaranteed a sufficient number of pupils, will open a children’s class in dancing at the Clubhouse Wednesday, October 15th. / Her terms are $2 in advance for four lessons and the hours are 2:30 to 5:30 p.m. … / … / Miss Nicol is well prepared for the work she is seeking to inaugurate in Mill Valley. She is a refined young woman who has had the best of training in the terpsichorean art. She is a graduate of Veronin Vestoss of the Imperial Ballet and also of Mahr-Miekowski of the Ballet Russe, who tells Miss Nicol he can give her no further technique. / …[14]

The success and duration of this and related efforts (classes for adults and high school students) are unknown, although various advertisements appeared through December 1919.[15] As for the touted associations with the Imperial Ballet and Ballet Russe, these seem more grounded in promotional exaggeration than reality. Still, Margaret persevered in her craft, performing locally at the behest of such organizations as Mill Valley’s august Outdoor Art Club.[16]

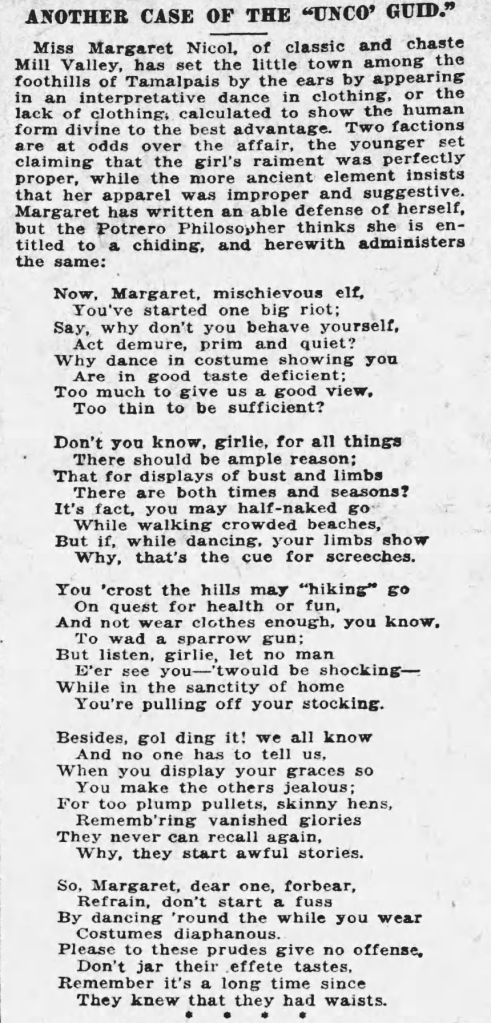

Influenced by Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, in May 1920 an unabashed, artistically progressive Margaret incited heated controversy when, garbed in a short, diaphanous costume, she performed al fresco a Grecian inspired dance at a Boy Scout benefit in Mill Valley. One imagines the Scouts heartily approved, but the town’s more staid citizens exploded with outrage. The Bakersfield Californian trumpeted: “Dancer’s Gauzy Grecian Gown Rends In Twain Suburban Town: ‘Indecent,’ Shout Church Folk: ‘Philistines,’ Retort Bohemians.”[17] Margaret remained unflappable:

Mill Valley, Calif., May 7.—Troy fell because of a woman’s beauty, and Mill Valley is split in twain over a classic dance. / Margaret Nicol, titian haired maiden of 16, is the center of a civic upheaval with the artists’ colony aligned on one side and the church folk on the other while adjectives like “prudish,” “Philistine” or “immoral” and “risque,” are being flung back and forth like shuttle-cocks. / It came about when Miss Nicol danced a Grecian dance on the hill-slope for the Boy Scouts entertainment. She wore a filmy costume and considerable of her beauty unadorned. / The good people were shocked. / A special meeting of the Congregational church was called and a letter sent Miss Nicol in which a committee of three advised her that the dance was “indecent, immoral and demoralizing.” The pastor and school principal spoke against it. / You are probably looking at it from your artistic standpoint,” they wrote, “but even the Greek dancing girls were outcasts from society.” / An uproar then went up from the artists, who dwell here in numbers. Ray Boynton and McLeod Batten, painters, denied that Grecian dancers were outcasts, and insisted that they danced in the temples as part of the religious ceremony. / As for little Miss Nicol she says she will continue to follow in the steps of Ruth St. Denis and Isadora Duncan. / ‘If these people had paid good money to see classic dancers in a theater they would have thought it moral,” she says smilingly. “Because I danced in the open air and was enjoying myself I am ‘immoral.’ Well, if that’s immorality I hope I am.’ [emphasis, the author][18]

The event even inspired this satirical poem by San Francisco Bulletin columnist C.M. Jackson[19]:

And The San Francisco Examiner emblazoned its front page with an illustrated article tantalizingly headlined “Dancer Makes Mill Valley Blush / Her Gauzy Garb Not Light Proof: ’Twas Grecian, So ’Tis Lewd, Critics Say.”[20]

The Margaret Nicol Weston knew and photographed eight years later may have been more mature and experienced, but not so far removed from her artistically precocious teenage self. Yet, despite her obvious allure, it wasn’t Margaret with whom Weston became enraptured, it was Amaryllis, Margaret’s less dramatic but similarly free-spirited younger sister.

A few weeks after his “mad whirl” with Margaret, Weston—longing for romance—opined: “… Another dance, and a bottle of wine, and a girl to love is what I need. The latter has not yet appeared on the horizon.”[21] His yearnings were soon fulfilled, for a mere three days later the beguiling “A” entered Weston’s life. October 15th found him rejoicing:

Always—and at the right time—my wishes are fulfilled: last night I took A. into my arms, and found her lips were waiting mine… / We met two days ago at Margaret Nicol’s. / Hardly a word was exchanged that night, but I noted her beauty of face and form, her fresh loveliness and refinement. We drove her home, and parting, I read her eyes. Next day, all day, she haunted me, until I called up Margaret to get her telephone. We planned a day together—lucky that Sunday followed—a day far away in the hills, lying in the sun, dreaming, each knowing well the other’s thoughts and desires,—and yet I did not touch her,—could not. I am always so, I cannot be aggressive. But I knew the evening was ahead!—and I would have surprises for her: music, a bottle of wine, the beauty of my room. And how we danced!—with ecstasy of knowing, yet waiting the moment. What an incorrigible romanticist I am. Who would not be with A.! Rich chestnut eyes,—frank, open eyes, golden hair to match, a slender, almost fragile body, yet well rounded,—seldom does one see more exquisite legs—and sensitive hands. All this is A. plus the freshness of youth. She may be virginal,—I almost think so. She is only twenty,—which means nothing, but seems untouched,—mentally wise but bodily inexperienced. / So I have what I wished for in my last entry,—dancing, wine, and a lovely girl.[22]

(Courtesy of Georges Rey and Cynthia Haggard)

Ah, the illusions of a self-proclaimed “incorrigible romanticist.” Amaryllis Nicol may have been youthful, but “virginal,” “untouched,” and “bodily inexperienced” she was not—as Weston would soon realize to his chagrin and, to an extent, relief. Still, it was an exhilarating encounter, as is clear from this October 24th Daybook entry:

Saturday night our first party here. Just Margaret, Irving, A., Brett, and Edward with a gallon of Burgundy. We danced—A. and I—and loved till I was sick of love—in a flame! Then Margaret suggested a drive to the beach, a run on the sands. / “Stay with me,” I said to A. / “No, not tonight, I have complications. I’ll tell you why later,” she answered. Oh hell, I thought, another virgin with inhibitions. I will not try much longer. But I wanted her. I was full of passion….. / We drove far and fast, seventy the hour at times, until kisses became more like clashing of teeth. And then she left me. / She came next day with evident desire, and I said to her, “I want you, do you want me?” “Yes—I did not stay last night, because we had been drinking, and because the others would guess. I am not an exhibitionist.” I liked her delicacy of attitude though it certainly was hard on me and took the edge off our first coming together. I was fooled. She was not a virgin, no indications at least. Maybe I am lucky, there will be no tears and regrets. But she gives me much beauty, and I have desire to reach a closer understanding and finer rhythm with A.[23]

Powerfully sexual, the resulting relationship was also fraught with complications and emotional challenges. The first such impediment was the presence in Amaryllis’ life of another lover, and a jealous one at that. Only two days after their initial consummation, Weston felt compelled to write:

A new experience is mine! I am wiser than I was. / And sadder?—not so much—a little thought. I will miss her dancing most of all. We danced well together, A. and I. An impassioned courting—the surrender—then the rocks! Sunday night after she had left I was just dozing off, feeling rather balmy over my success, when the phone buzzed—I have it well muffled. / “Is Miss—there?” / “No” / “Do you know where I can reach her?” / “No.” I hung up and dove into bed. Again the phone—this time I was asleep—and rather peeved to shiver in my nakedness. / “Is Miss—there?” / “No!” / “A friend of hers is dying—are you sure she is not there?” Now I was angry,—being called a liar—indirectly, though I would have said “no” if she had been here! I hung up abruptly. But now I was wide awake and smelled a rat. / A jealous lover, of course! Well I want no triangles,—no one is worth such a mess. / Two days later, a note from A., certain things had happened, and she thought best not to come out again, regrets, etc. / The name given me over the phone was someone Lula Boyd [Stephens] knew. I will go to her, perhaps she will enlighten me. She did! / A. had been using me to incite jealously, or perhaps using both of us. So thought Lula. She told the whole long story, in confidence. / Who would have thought it of you, A.? / Well, I shall be fortified if you should change your mind or heart and come again- – – [24]

And the next day brought this melancholic rumination:

The broken rhythm has let me down. I am not so depressed as I am wistful. I play Horas Tristes that we danced so often together, wondering what next. I was gay and happy these last weeks, I needed just what A. gave me, to relieve the daily drudgery. It surely was not real love I felt for her, I was in love with the idea. But what is love? What has happened to the many girls I have thought I loved? Is love like art—something always ahead, never quite attained? Will I ever have a permanent love? Do I want one? Unanswerable questions for me![25]

It was a roller coaster romance: Optimism to dejection; appreciation to resignation; delusion to self awareness—an exhausting cycle that would only conclude with Weston’s departure, in late December, for a new life in Carmel. However, in October the experience was still fresh and Weston, feeling both hopeful and cautious, wrote on the 31st:

I have had a definite feeling that my contact with A. was not over: that she would return, and that she was not merely using me. I know when a woman really cares. There came a beautiful letter while I was developing. Maybe my indifference to the tragedy [Weston is referring to double exposed negatives taken during a commissioned portrait sitting] was due to the renewed joy this letter brought. She did not ask to return. She did express her love and sorrow, and hope of forgiveness for the hurt. I would not have liked an open request for return. But A. is too fine for that. / I admit I want her. She complements me well. / We walked by Lula’s last night. I stopped to ask her to join us for supper. A. had talked with her! And Lula had changed her mind. “She sincerely cares for you. I misjudged her.” It seems Lula is destined to be the mediator. I wrote A. I did not ask her to return. But I told her I had no bitterness, and would make no embarrassing gesture if perchance we met. She, if wise, can read between the lines. She will. We are fated to be together again. And maybe the stronger for this test. / But A. must make the first move, and show me clearly her desire.[26]

By early November, following a brief setback, he was positively rhapsodic:

No love affair in years has so deeply moved me as this with A. and the renewal was more profound than the beginning. I had felt at the start that she, though excited and responsive, was withholding something of herself. But the coming together of the other night was perfect. She completely surrendered. A sweeping, surging, unrestrained rhythm coursed between us: we two became as one.[27]

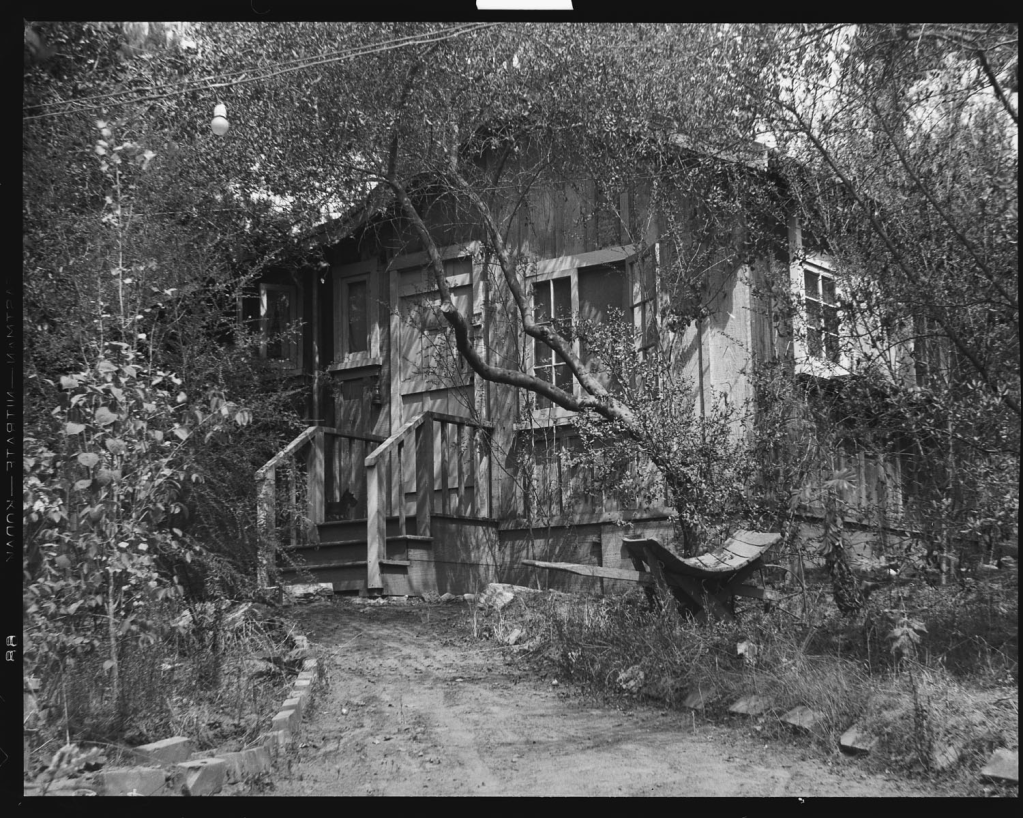

A week later, the couple spent an equally erotic weekend cocooned in Hagemeyer’s Carmel abode:

The weekend of A. and Edward is now a memory,—a rare and perfect one. Hours of exquisite delight for me,—and I am sure for A. too,—seeing, feeling, her response. / I have had women, burning with passion, women stirred with romance, sensual women: but no one who has quivered in my arms so sensuously responsive to my caresses as this slip of a girl. / So—my own approach being sensuous rather than passionate, the union was well-nigh perfect. / We danced! — tangos & danzóns: A. is always ready to dance. Jean Roy furnished a bottle of wine, “to help along a good cause.” The second night a few glasses at Ray Boynton’s fanned the flame—though fanning was superfluous—and the last night a bottle of gin was found in Johan’s cupboard cheered our departure. A roaring grate fire fed by driftwood was the focus for lazy, dreamy hours: we kept it crackling day and night— / Acordate—Mocosita—Sonsa—Horas Tristes!—music that will always recall you, niña de la primavera![28]

(Johan Hagemeyer Photographs, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, BANC PIC 1964.064.536 NEG)

Alas, such heat, energy and commitment were not to last—due, in part, to the couple’s rather wayward approach to relationships. Recognizing this shortcoming—not least of all in himself—Weston began contemplating its repercussions:

Brett went away for the evening so A. and I were alone to talk. / She will be my mistress, wants to be, cares for me,—but Lula does not approve. This is not going to be pleasant,—she is living with Lula. Probably Lula is being ethical, A. must have talked with her as with me: that she cares for this boy who has gone away for a year or two, but sees no reason why she should be true for so long a time. / I, of all persons, have no right to complain, not when I have had three affairs at once, three or a a half dozen! Yet my ardour is somewhat cooled. I want to be the whole thing, or at least not second fiddle, which I very likely am. / I am basically constructive, much of the home builder in me. Many would laugh to hear this, but I feel it is so—I pretend to myself—not always—that this affair—the latest—is a lasting one. I start to construct the future—I believe in my plans. I would take A. out of her office work, teach her photography, make her independent of a job. But how can I build enthusiastically, knowing some one else is in the background. / Yet my whole reasoning becomes ridiculous in the face of my past record. And how can I promise anyone anything—with four boys to consider![29]

On December 7th, he wondered: “A.? Am I so fickle? Something is wrong with our affair. My fault or hers, I don’t know.”[30] And a day later he assessed the pending dissolution with an honest self-appraisal:

… I awakened with thoughts of A. She is coming this afternoon—and I know beforehand what for: to tell me that we should part. She has been avoiding me with various excuses, too obvious excuses. Real desire overcomes all obstacles. She claims deep melancholy, megalomania, and I know she is subject to depression. But if I had even temporarily “inspired” her, she would be buoyed up and happy. Somehow I have failed,—why, I shall try to find out for my own education! / Am I sad with the thought of parting? No, though I wish the affair could have lasted longer. Now unless the aspect of our association changes, I want it definitely over. / I need someone to be gay with, not one who needs continual cheering. I “kid” myself better than most of my friends. I have my work to fall back on. / … / Thinking over A. again, maybe I am all wrong as to why she wants to come today. Maybe my thoughts are prompted by my desire….Maybe I am the one who wants to end it all and she receives my wish. / …[31]

Regardless of who was responsible for ending the affair, after another brief sputter, end it did. Weston’s upcoming departure for Carmel led him to disassociate from his San Francisco life, and on December 16th he recorded this somewhat melodramatic coda to the tempestuous relationship:

… I shall be glad to go—have already gone—mentally I am no longer here. / I have left A. too. Yesterday I said good-bye, and she it was who wept—though maybe not all the tears were for me—since M. [Margaret Nicol?] also left for Germany. I was emotionally torn, she seemed so sad and worn—physically—psychically. / But I knew the time had come,—after the farewell party at M. Saturday. I hardly seemed to touch her that night—and she flirting desperately with some tall blonde. Perhaps I should have tried to win out. But it’s not my way. I shrug my shoulders, freeze and indulge in mocking laughter. / … She called me next morning, her voice had remorse, “I am miserable—for many reasons, will you come and sit by the fire?” I went to her. / “Have I hurt you, Edward? Tell me.” / I told her she had not, but circumstances, life had hurt. Hurt may come from chagrin, disappointment over wasted affection. The feeling of having given to another is so very important, more so than the smug satisfaction from receiving only. / So I said farewell, that this would be our last meeting, that I was busy packing. She choked, and said, “Go quickly, Edward.” / What did I do, or not do, to quench the flame which seemed to flare at Carmel?[32]

As illustrated in California—Magazine of Pacific Business (May 1937): p. 34.

A BOHEMIAN BACKGROUND

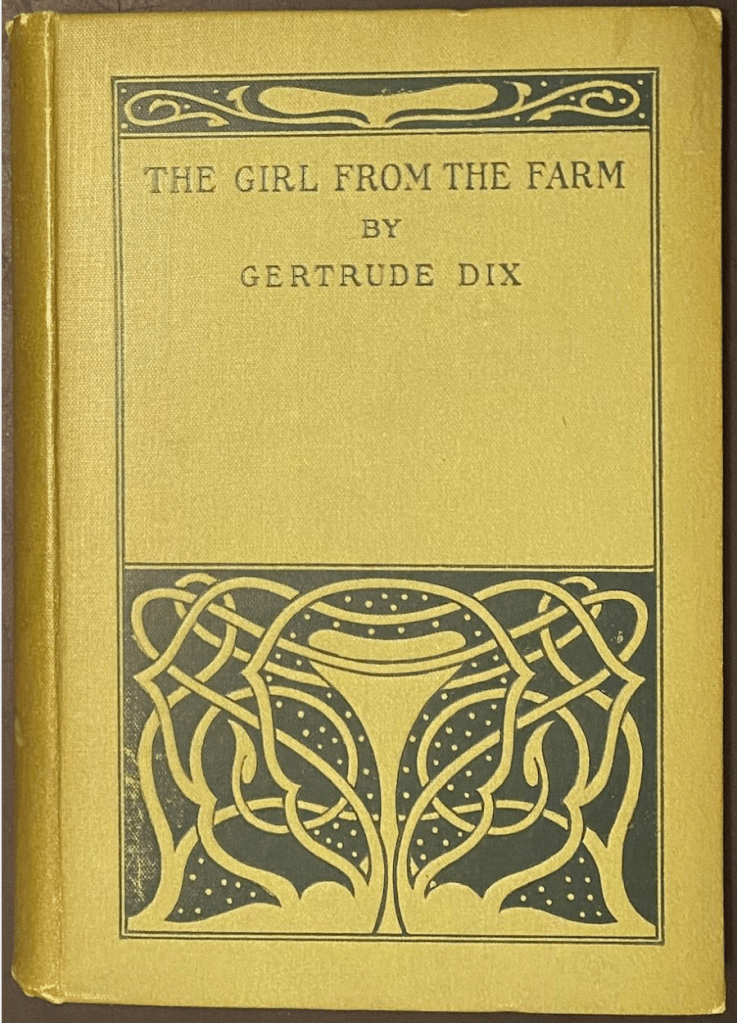

So, who, exactly, were the beguiling Nicol sisters? As noted previously, Margaret and Amaryllis—as well as a brother Robert (1908-1997)—were the offspring of quintessentially bohemian parents: Robert Allan Nicol (b. Dunfermline, Scotland 1868–d. San Francisco 1956) and Gertrude Dix Nicol (b. Brixton/Bristol, England 1867–d. San Francisco 1950).

The epitome of late 19th–early 20th century free-thinkers, Robert Nicol and Gertrude Dix were dedicated Socialists, labor activists, intellectuals, sexually liberated, and radical. Both were gifted writers—an aptitude that earned Gertrude, a member of the Fabian Society, a reputation as a “New Woman” author whose novels The Girl from the Farm (1895) and The Image Breakers (1900) gained modest celebrity in England and the United States.

Although Robert and Gertrude originally met in Bristol during the 1880s, it wasn’t until the early 1900s—after both had emigrated to the United States—that their relationship coalesced. Robert was the first to arrive, settling in the Boston area in 1890 with his (already married) lover, the Socialist writer/poet/activist Elizabeth Miriam Daniell (then pregnant with Robert’s child, a daughter they named Sunrise).[33] In 1893 the family departed Boston for a fresh start in the Sierra Nevada mining and ranching town of Weimar, California.[34] Sadly, this new life proved brief, for Miriam passed away in 1894.[35] Following Miriam’s death, Robert and Gertrude rekindled their earlier acquaintance via correspondence and, in 1902, Gertrude sailed from England to join Robert in Weimar (where Margaret, Amaryllis and Robert would be born).[36] The [Auburn] Republican-Argus announced the couple’s April 1903 marriage as follows:

R.A. Nicol of Weimar, and Miss Gertrude Dix of London, were united in marriage by Justice Wills last Wednesday, April 8th. The bride is an English story-writer of considerable note, two of her best known novels being “The Girl from the Farm” and “The Image Breakers.” Mr. Nicol is a newspaper writer, and has filled important positions on some of the leading publications in this country and England. Mr. and Mr. Nicol have established their home on their ranch at Weimar.[37]

Theirs is a captivating tale, far too complex to detail here. Gertrude continued writing, although with diminishing success as the times and literary tastes evolved.[38] Robert was, by all accounts, exceedingly charming but romantically inconstant with a tendency to professional insouciance, engaging in various mining and other business ventures without much success. Although they encouraged their children’s artistic inclinations[39], the couple weren’t always attentive parents, abandoning them in Mill Valley in 1920 while Margaret, Amaryllis and Robert were teenagers.[40] Yet, the family remained in contact over the years and Robert and Gertrude weathered their relational vicissitudes to spend their final years together in San Francisco. Sheila Rowbotham, the esteemed feminist historian, details their lives and those of their radical cohorts in exemplary fashion in her 2016 book, Rebel Crossings: New Women, Free Lovers, and Radicals in Britain and the United States.[41] I highly recommend this fascinating study.

(Both images Courtesy of Georges Rey and Cynthia Haggard.)

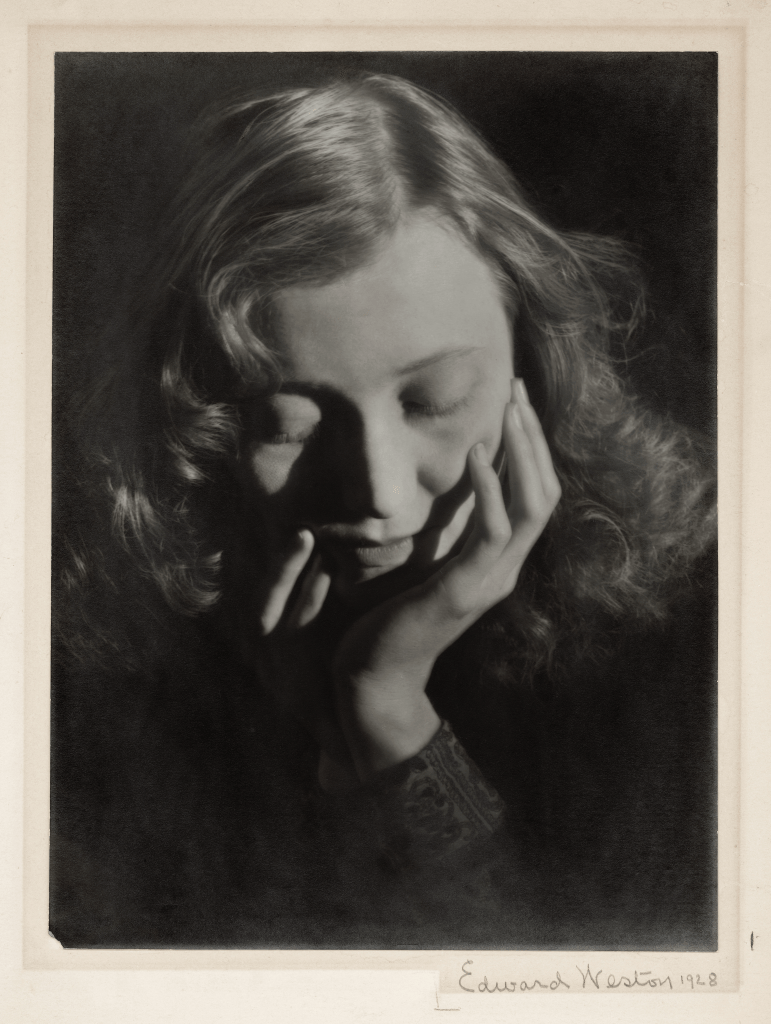

KNOWN WESTON PORTRAITS OF THE NICOL SISTERS

To date, only one Weston photograph of Margaret and three of Amaryllis have been identified. All are illustrated in this post. Yet, Weston’s Daybook entries make clear that many more negatives were exposed and printed, including the series of Margaret’s dance poses noted above. On November 5th Weston writes of an additional, informal, image of Amaryllis: “The only print that half way pleases is of Lt. Novill. Yes—another, A. prone in the grass, sunlit. Just a sentimental record.”[42]

Apparently, Weston made portraits of Amaryllis on Sunday, November 17th, as indicated in that day’s Daybook entry: “A. came to supper last eve. We became gay with wine and wound up at Margaret’s, dancing until 2:00. These diversions are most salutary for me. She is coming this afternoon, and will sit to me. Question—will the sitting be incidental?”[43]

Happily, the experience was a fortuitous one that yielded images Weston felt captured the essence of the woman he perceived Amaryllis to be. The next day he wrote:

All else was incidental to the sitting. She had to leave early, and we were both wan and weary from the night before. But I worked well, despite, and have her, — captured that childlike loveliness,—golden hair circling her face like a halo, frank, tender eyes, wistful smile: eyes and mouth that fooled me, so virginal they are. Yet they will never grow sophisticated, never hard, calculating: too sensitive, too delicate her gestures and attitude toward life.[44]

(Courtesy of Georges Rey and Cynthia Haggard

An equally positive assessment on November 29th reflects Weston’s working process and aesthetic sensibility:

… I finished and took to “mi niña” one of her new portraits. It could be sentimental, will be thought so by most of my friends. I say “could be”: if I had told her, “Now put your hands so, under your chin, and register dreaminess,” then it would have been. But the actuality was quite different. She sat there in the sunlight, waiting, dreaming: perhaps her thoughts were of me, maybe—more likely—far away with another love,—it makes no difference, I saw a moment, lovely but not banal, and caught it. / More difficult this, more subtle, than to record an heroic head of a strong man. There is danger in always searching for obviously powerful subject matter, or using obviously perfect forms.[45]

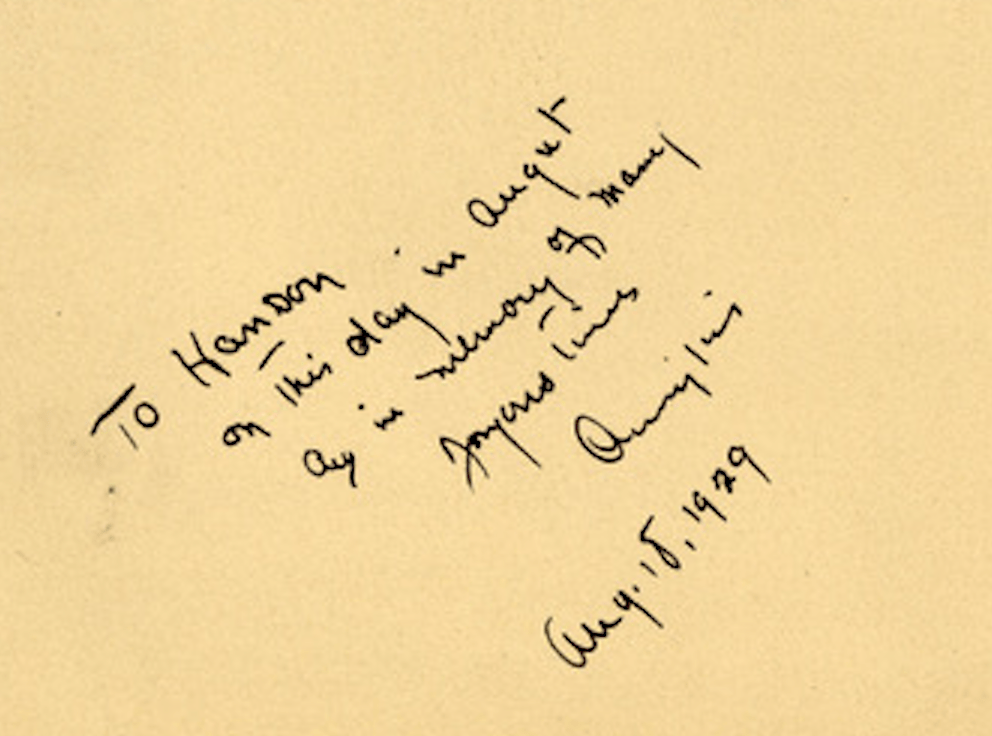

These tantalizing descriptions convey the impressions of a man in the first throes of infatuation. However, Amaryllis seems to have been happy with the portraits as well. Nearly a year after the end of her relationship with Weston she gifted a print to someone she clearly cared for, inscribing it: “To Hanson [Handon?] / on this day in Augut [sic] / and in memory of many / Joyous Times / Amaryllis / Aug. 15 [18?], 1929.”

(Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, Museum Purchase; 1988.39)

The trail of Weston’s relationship with the Nicol sisters concludes with these photographs and Daybook entries. Hopefully, this essay will prompt additional collectors and curators to recognize Margaret and Amaryllis among the Weston portraits in their collections. If so, I would love to hear from you!

AMARYLLIS & MARGARET: EPILOGUE

The circumstances and dates surrounding Amaryllis’ and Margaret’s journeys to San Francisco remain hazy.[46] Amaryllis’ path is especially sketchy, but Margaret, prior to landing in San Francisco, reportedly spent time in Santa Cruz, New York and Carmel—where she “taught at an out-of-door [dance] school.”[47] When Weston met them in 1928, the sisters were making ends meet as office workers. It’s likely Margaret was pursuing her dance career as well. Although their trajectories differed greatly, both women eventually settled in New York City.

Unlike the flamboyant Margaret, Amaryllis seems to have led a quiet life out of the artistic limelight. She played piano as a child,[48] but this never became a serious pursuit as did dancing for Margaret. Consequently, newspaper and other published references are elusive. She had moved to Manhattan by 1930 when that year’s Census recorded her as a “Secretary” living as a “Roomer” at 303 West 19th Street.”[49] She married twice. First, in 1934, to a writer (described thus in the 1930 Manhattan Census) named Theodor S. Ruggles[50] then again in 1943 to Ury S. Cabell (1916–1987),[51] with whom she had a son, Stephen (1944-1984).[52] While I cannot positively identify which Ury S. Cabell this was, it’s tempting to think he may have been the Cabell photographed by George Platt Lynes in 1938.[53] When the marriage ended she retained the name Cabell and is listed as such on her 1983 Social Security Death Index record.[54] According to Amaryllis’ half-nephew, Georges Rey, hers was not a particularly happy life, but as Georges reflected: “I grew very fond of her, and was impressed by her intelligence and care in recounting memories.”[55]

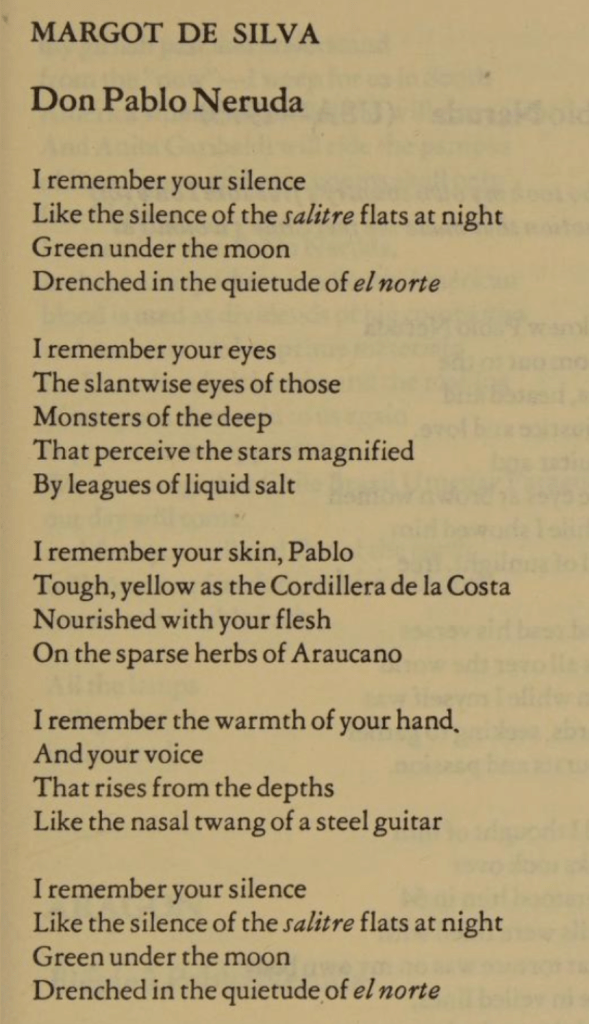

Margaret, or Margot as she later called herself, remained ever true to her unconventionality and artistic inclinations. In addition to dance, she wrote poetry, erotic short stories, articles, and even a novel (unpublished).[56] After leaving San Francisco for Germany[57], she lived in a number of cities, including Paris, Santiago, and, ultimately, New York. Like her sister, Margot married twice, first around 1925 to Arthur Gunderson, a violinist in Santa Cruz, California.[58] In a rather untraditional marriage for the time, Margaret toured and lived apart from Gunderson for extended periods.[59] Her second husband, whom she married sometime in the 1930s, was Alvaro De Silva, a Chilean writer and consular attaché whose name Margot would keep for the remainder of her life. While in Santiago, the couple associated with the poet Pablo Neruda, a relationship that certainly influenced her poem “Don Pablo Neruda,” which leads off Walter Lowenfels’ 1975 book, For Neruda, For Chile: An International Anthology.[60]

Not surprisingly, Margot maintained an unapologetically bohemian life after moving to New York in the 1950s. As Georges Rey recounts:

Sometime in the 50s, she moved to New York, where she lived in a fifth floor walk-up in New York’s (then) fairly decrepit East Village (my mother offered to move her to a more comfortable place, but she would have nothing of it… / …When I got to know her in the late 70s, Margot was reading erotic poetry to jazz accompaniment in Village dives and having affairs with men half her age (I went to one of her readings—and met one of them—at the famous Cedar Tavern, where she had hung out with the New York abstract expressionists). There she was, almost 80, gnarled with arthritis, but, in a quite distinctive way, amazingly sexy: she did have lovely skin, and exquisitely high cheek bones, and a penetrating blue-eyed stare. But what was most important was what visibly appeared to be a perfectly sincere, apparently insatiable—but never the least bit vulgar—preoccupation with sex.[61]

My chance meeting with Cynthia Haggard and Georges Rey has brought the Nicol sisters’ identities and stories to light. One wonders if Weston himself knew the fascinating family history behind the “frank, open eyes” of “A” and the “evanescent gestures” of Margaret. As for Weston’s restless quest for “true love,” these brief but drama-laden relationships with Amaryllis and Margaret add rich perspective and substance to our understanding of Weston’s search for a romantic life partner.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to extend a very special note of gratitude to Georges Rey and his wife Cynthia Haggard, without whom the Nicol sisters’ identities and story would not have come to my attention. Their openness and generosity in sharing their family photographs and history proved of incalculable value.

Additional thanks go out to Frank Goodyear and Anne Collins Goodyear, Co-Directors of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. Prior to publication of this post and its “reveal,” Frank contacted Paul Hertzmann and Susan Herzig to ask if they could identify the subject of a portrait titled merely “Amaryllis” in the museum’s collection. His timely inquiry not only introduced me to a superb third portrait of Amaryllis but spurred on the writing of this blog.

NOTES

1 Edward Weston. The Daybooks of Edward Weston. Vol. 2, California. Edited by Nancy Newhall. Millerton, N.Y.: 1973. 15 October 1928, p. 83.

2 Ibid. 24 August 1928, p. 69.

3 One of my fellow travelers on a Smithsonian Journey’s trip to Greece was the charming and accomplished author, Cynthia Haggard. During an initial conversation, I told Cynthia of my work on Edward Weston. “My husband has a couple of Weston portraits of his aunts,” she revealed. Naturally, my curiosity was piqued, but I assumed these would be examples of Weston’s commercial portraiture—always artful but of interest mainly to the sitters’ families. We exchanged contact information with the promise to communicate after the trip, at which time she would email me further details and images. Imagine my amazement when the portraits of Amaryllis and Margaret Nicol arrived in my inbox along with a brief biography of the extraordinary Dix-Nicol family compiled by Georges Rey, Cynthia’s husband. Amaryllis was Weston’s “A,” I was sure of it! Little did I imagine upon first learning of these half-aunts (see Note 55, below) that, in addition to being fascinating individuals in their own right, their lives would provide an illuminating addition to Weston scholarship.

4 “Events at the Hagemeyer Studio,” The Carmelite, 18 July 1928, p. 2.

5 Op. cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 4 October 1928, p. 80. Hagemeyer’s return wrought temporary domestic tumult. On 4 October, Weston wrote: “And the beginning of our new venture at 2682 Union St.—the end of Room 404, 117 Post. [sic; Hagemeyer’s studio was at 177 Post Street] … Johan sleeps. He will stay here until an apartment is found… Such confusion! No place to put things, no furniture,—the floor a dumping ground. I don’t like it.” By November, Hagemeyer had moved to 2929 Scott Street (San Francisco City Directory 1928–1929, p. 723). On 3 November, a relieved Weston wrote: “Johan has moved. We have less confusion,—more room!” Ibid. 3 November 1928, p. 87.

6 Ibid. 24 August 1928, p. 69.

7 Ibid. [16 September] 1928, pp. 73–74.

8 “The Carmelite Calendar: July 18 Hagemeyer Studio—4:00.” The Carmelite 1:23 (18 July 1928): 2. [No Illus.] and “Among the Artists: Artists of Brush and Camera Mingle at Hagemeyer’s Studio.” The Carmel Pine Cone 14:28 (13 July 1928): 4. [No Illus.]. This article reads, in part:

The Hagemeyer Studio continues to be a place where artists and their friends meet. / During the week, guests at the studio and home of the artist were Henrietta Shore, artist of San Francisco, and Edward Weston and his son Brett, photographers of San Francisco. / The Shore exhibit, long promised to Carmelites, is now an assured fact, and will open on July 21, when at an informal afternoon affair, Elsa Naess, Norwegian pianist, will entertain the guests [sic; According to the Calendar listing in The Carmelite, all three events opened on July 18th.] / She will play from the compositions of four contemporary Norwegian composers, Christian [indecipherable], David Johansen, Halfden Cleve and Backer Groundahl. Miss Naess, who is spending the summer here, is an acomplished [sic] young musician, and will play the music that she knows and loves by right of birth, and study in her native land. / The Shore exhibit will realize for art lovers here a pleasure greatly anticipated since Hagemeyer announced its possibility several weeks ago. / Henrietta Shore is an artist of striking individuality whose work bears the same stamp. / … / Mr. Hagemeyer promises us an exhibit of the Weston prints when the Shore pictures are removed. At the present time the Westons—father, and son—have a show at the East West Gallery in San Francisco. Weston’s photography has been attracting wide attention and comment from artists and critics around the bay. It will be interesting to see them here in as ideal surroundings as the Hagemeyer studio. / … / Hagemeyer is contributing much to the art life of Carmel not only by his own work, but by his appreciation of the work of his contemporaries, which he is bringing to us during the months he will occupy his studio.

9 “Alphabetical List of Names” in Crocker-Langley San Francisco Directory 1929. San Francisco, California: R.L. Polk & Co. of California, 1929, p. 723. A separate listing for Hagemeyer in the “Photographers” section on page 1739 reads simply: “Hagemeyer, Johan 177 Post R404.” Oddly, neither the 1928 nor the 1929 Directories list Hagemeyer on Union Street. The 1928 Directory notes: “Hagemeyer Johan photogr 177 Post R404 r 1032 Sacramento” (Naess does not appear in the 1928 Directory). Neither Hagemeyer nor Naess appear in the 1930 Directory. I was unable to locate an online version of the 1925 Directory, but Hagemeyer is not listed in the 1926 edition.

10 Op. Cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 4 October 1928, p. 80.

11 Ibid. 5 October 1928, p. 80.

12 Ibid. 6 October 1928, p. 80.

13 Department of Commerce–Bureau of the Census. Fourteenth Census of the United States: 1920–Population [Mill Valley, California]. The family lived in Sausalito earlier in 1919 but seems to have moved to Mill Valley around October. Family tradition suggests that Robert Allan Nicol (Margaret’s father) may not have been with them in Mill Valley, but the 1920 Census lists the entire family at 378 Cascade Drive, describing them as follows: “Nicol, Robert, Head, age 59, Occupation–Mining Engineer; Gertrude, Wife, age 46; Margaret, Daughter, age 16; Amaryulls [sic], Daughter, age 14; and Robert, Son, age 11.” Although Gertrude was an author, the Census records her without an occupation.

14 “Prospective Dancing Class: Children’s Class Planned to Begin this Month.” Mill Valley Record (4 October 1919): 1.

15 Advertisements for ballroom dancing classes as well as dance classes for both high school girls and adults appeared in the Mill Valley Record through December 1919. Examples may be found in the following issues: “Announcement.” Mill Valley Record (1 November 1919): 1. [“fancy dancing” for high school girls and “folk dancing and gymnasium work” for adults] and “Announcement.” Mill Valley Record (6 December 1919): 1. [ballroom dancing class].

16 “Dancing Class.” Mill Valley Record (11 October 1919): 1. The Outdoor Art Club was, and remains to this day, located in a beautiful Arts & Crafts style Clubhouse designed in 1904 by renowned Bay Area architect, Bernard Maybeck. The above-noted article reads, in part: “Miss Margaret Nicol, whose announcement of intention to start a children’s dancing class appeared in the Record last week, gave two well-executed solo dances before the Outdoor Art Club Thursday afternoon. Her numbers were received with appreciation notwithstanding she lacked good musical support. This deficiency has been remedied for the dancing class by the selection of a well-qualified musician for that feature of the class work. /…”

17 “Dancer’s Gauzy Grecian Gown Rends In Twain Suburban Town: ‘Indecent,’ Shout Church Folk: ‘Philistines,’ Retort Bohemians.” The Bakersfield Californian (7 May 1920): Sec. 2, p. 1.

18 Ibid. This article and photographic illustration also appeared on the front page of The Sacramento Star on 10 May 1920.

19 C.M. Jackson. “For Instance: Another Case of the ‘Unco Guid’.” San Francisco Bulletin (11 May 1920): 11.

20 “Dancer Makes Mill Valley Blush / Her Gauzy Garb Not Light Proof: ’Twas Grecian, So ’Tis Lewd, Critics Say.” San Francisco Examiner ( 6 May 1920): 1. This article reads:

When is a classical dancer?” is a question that has split in twain the wooded bowers and evergreen homestead of Mill Valley since a spotlight operator turned too much light at Miss Margaret Nicol, an exponent of the Grecian dance. / If Mill Valley can produce a Duncan or a Morgan, the community should be proud of her, declare those residents who dally with art either professionally or as amateur worshippers at its shrine. / The young people and children of Mill Valley must not be demoralized by such intimate exhibitions of Miss Nicol, assert some members of the Women’s Society of the Congregational Church, of which the Rev. E. C. Oakley is pastor. / Mrs. James Steward, secretary of that church society; Mrs. Evan Espseth, its treasurer, and Mrs. George McConnell signed and sent to Miss Nicol this letter: / ‘Dear Miss Nicol: We desire to protest against dancing in costume of the nature worn by you at the Boy Scout benefit performance. We feel that it is demoralizing to the children and young people of the town. We feel that it is a result of false training. / ‘Your training has probably unfitted you to see such matters in the same light that the general public does. You are probably looking at it from your artistic standpoint. / ‘You are possibly thinking of copying the Greek dancing girl in giving a classical dance. But the Greek dancing girl was an outcast from society, even in those days, when they never conceived of the high moral standards that we have today.’ / Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Brand, whose home is in the storm center have sprung to the defense of Miss Nicol. Speaking for Mrs. Brand and himself, the attorney said: ‘In leveling their shafts at Greek classical dancing and at the Grecian women, whose semi-sacred performances in the dance have come down to us through the centuries, the attackers of Miss Nicol were particularly unfortunate. Their sneers at the moral standard of ancient Greece will strike every student of ancient history as ridiculously smug. / ‘The women and girls who danced in the theaters of Athens were quite the opposite of ‘outcasts from society. They often were taken from the temples. They generally were of the patrician families. / ‘Their dancing, which Miss Nicol was interpreting with all the modesty of an American girl of the highest moral standard, undoubtedly was a part of Greek religion. Miss Nicol lives close by us. She is a very modest and proper little girl and her numerous friends hope she will succeed in her art.’ / Mrs. McLeod Batten, a painter, whose studio is in Mill Valley, eulogized Miss Nicol’s dancing. / ‘Those of us in this community who are not prudish resent this attack upon Margaret Nicol, whose mother is her accompanist in many hours of earnest practice.’ she said. ‘Why should not Mill Valley give the world a classic dancer equal to Isadora Duncan or Ruth St. Denis or Marian Morgan?’ / Mrs. Ray Boynton, who sings; Ray Boynton, who paints; Miss Dorothy Wilson, also a painter; Mrs. I.E. Wilson, her mother, and other members of Mill Valley’s colony that cultivate the fine arts, proclaimed unhesitatingly their championship of Miss Nicol.

21 Op. Cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 12 October 1928, p. 83.

22 Ibid. 15 October 1928, p. 83.

23 Ibid. 24 October 1928, p. 84.

24 Ibid. 26 October 1928, pp. 84–85.

25 Ibid. 27 October 1928, p. 85.

26 Ibid. 31 October 1928, pp. 86–87.

27 Ibid. 7 November 1928, p. 89.

28 Ibid. 14 November 1928, p. 91.

29 Ibid. 9 November 1928 p. 90.

30 Ibid. 7 December 1928, p. 96.

31 Ibid. 8 December 1928, pp. 96-97.

32 Ibid. 16 December, 1928, p. 16.

33 Sheila Rowbotham. Rebel Crossings: New Women, Free Lovers, and Radicals in Britain and the United States. London and New York: Verso, 2016; p. 94. Sunrise Nicol was one of two illegitimate daughters sired by Robert Allan Nicol. See Note 54, below.

34 Ibid., p. 142–143.

35 Ibid., p. 149.

36 On her official United States of America Declaration of Intention and United States of America Petition for Naturalization, (filed in San Francisco on 14 and 17 February 1942), Gertrude reports that she arrived in New York on 17 February 1902 aboard the SS St. Paul. She also notes that Robert arrived in New York in 1892. This is incorrect. Robert originally emigrated to the United States with Elizabeth Miriam Daniell in 1890. What is true, however, is that Robert and Miriam moved briefly from Boston to New York in 1892 before returning to Boston and finally leaving for California. Perhaps Gertrude was either attempting to gloss over Robert’s earlier alliance or simply mis-remembered the date of Robert’s arrival.

37 “Local Intelligence: R.A. Nicol of Weimar, and Miss Gertrude Dix of London…” [Auburn] Republican-Argus (22 April 1903): 3. NOTE: The marriage date of 8 April cited by the Republican-Argus may be incorrect. On her initial “Declaration of Intention” for Naturalization application, filed on 14 February 1942, Gertrude cites the marriage date as 25 April 1902.

38 Some of the published works written by Gertrude Dix early in her California life are reviewed in the following: “A Talented Placer County Writer.” Placer Herald, 25 February 1905, n.p. and “The Sunday Call’s 50 Dollars a Week Prize Story: ‘Pardners’ by Gertrude Dix.” The San Francisco Sunday Call, 3 April 1905, p. 3. NOTE: This article is presents the full text of Dix’s award winning story, “Pardners.”

39 In 1912, the children appeared in a theatrical performance at their family’s Auburn, California home. This fanciful, two-act comedy, Nobody Knows My Name, was written by their accomplished mother. Margaret assumed the role of “Fairy Cobweb,” Amaryllis that of “Fairy Buttercup,” and little Robert that of “Jingle, an imp.” The occasion was reviewed in: “Nobody Knows My Name.” Placer Herald, 3 August 1912, p. 5.:

The open air performance of “Nobody Knows My Name” at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. R.A. Nicol, “The Cypresses,” on Prospect Hill Monday evening was a delightful and successful affair. / “Nobody Knows My Name” is a fairy comedy in two acts, written by Gertrude Dix, (Mrs. R.A. Nicol) and this was the first presentation of the play. / Those who appeared in the characters of the comedy acted their roles with charming naturalness, making each situation of the comedy a perfect picture of a fairyland, and meriting the hearty applause bestowed on them by the audience, composed of about one hundred neighbors and friends. / … / The natural beauties of the open air stage, artistic arrangement of the lights, and the elegance of the costumes worn by the players were a fitting accompaniment to the daintily told fairy love story, and contributed greatly to the success of the evening’s pleasure. The costumes of the actors were designed and made by Mrs. Nicol. / … / It is proposed to present other plays from the pen of Gertrude Dix during the year, as the night climate of Auburn is emminemtly [sic] suitable for outdoor performances.

40 It has been suggested that Robert, on the point of leaving Gertrude for another lover, catalyzed her into following him in order to save their marriage. The length and impact of this desertion is unknown to me, although the children remained involved with their parents throughout their lives. More details regarding the family relationships may be found in Sheila Rowbotham’s book, Rebel Crossings.

41 Op. Cit. Rebel Crossings.

42 Op cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 5 November 1928, p. 88.

43 Ibid. 17 November 1928, p. 92.

44 Ibid. 18 November 1928, p. 92.

45 Ibid. 29 November 1928, pp. 93-94.

46 Neither Amaryllis or Margaret appear in the San Francisco City Directories at any point in the 1920s. Unlike his sisters, who seem to have fended for themselves, the younger Robert was sent to boarding school and eventually settled permanently in San Francisco.

47 “Mrs. Gunderson, Lovely Dancer, Back From Little Old New York Tells of Metropolis Life,” Santa Cruz Evening News, 9 May 1925, p. 7. This article reads, in part:

Margaret Nicol, who in private life is Mrs. Arthur Gunderson, wife of the local violinist, is back from a stay of several months in New York City; and a News representative called upon her to hear about her experience of life in “the little old town.” Mrs. Gunderson is known to many here, although she has been away most of the time, two years, during which her husband has been playing in the theaters of this city. / Her dancing has not been forgotten by the few who have been privileged to see it. She is grace itself, and by no means her smallest asset is her lovely, serious face, with its fair skin and its dark, expressive and intelligent eyes set in a frame of auburn hair. / She found New York so big it made her gasp. “I should like to live there for a couple of years or so—it is fascinating, just because there is everything there for which one could wish. But I should never want to live my whole life there. When you get away in the midst of the rush and the turmoil California seems like a beautiful dream of paradise—ever so far away. / Musicians Crowd in From Europe / “What I went for was to find my bearings. I long to do professional work, and have had the training for it. But I wanted to know what was going on at the heart of things. Then I wanted to see, if I found what I could do there, if it would be feasible for Mr. Gunderson to come on. Everywhere they old me, “For heaven’s sake, if he has a position in the West, have him stay there.” They advise musicians to keep away from New York. The market is flooded with European musicians on account of the poor conditions across the water. Musicians of long standing there told me that they were most thankful for their jobs.” So that is that, and I came home for the time being anyway, when Mr. Gunderson begged me to. / “Dancing is different from playing an instrument. I had several offers which were attractive. One would have taken me to Paris. But that was too far from California.” / … / “I went to many schools of dancing to see what they were doing. The most interesting was the Jacques Dalcroze School of Eurhythmics. This mystic word means “Better Rhythm.” Music pupils take the course, which is valuable to many people—indeed, to anybody. It is training in co-ordination. Feet will be carrying on one rhythm, hands another. Dalcroze is a Swiss teacher. / “Then there is the Florence Fleming Noyes school of dancing which is excellent. And hundreds more. / … / Asked what she was going to do now, Mrs. Gunderson shrugged her shoulders, and said that had to be worked out. She has, in the short time she has been a professional, done interesting things. She was last year with a private company which toured the entire state of California, giving, in connection with motion pictures harmonizing therewith, “The Vision of California,” a dancing and singing act like a miniature concert. / The year before she taught dancing at Carmel at the out-of-door school there. She had done a number of other things. And she will soon be heard from again in professional circles.

Perhaps Gunderson is the “lover” to whom Weston was referring when he wrote the following about Margaret on 16 September: “Reservations were cast aside: I had heretofore made no gesture because of her lover.” Daybooks, vol. 2, California. [16 September] 1928, pp. 73–74.

48 “Piano Recital.” Sausalito News, 11 August 1917, p. 1. Both Amaryllis and Margaret performed in this recital by the “juvenile class of Miss Romana Mulqueen… in Mulqueen Studio.” Amaryllis played an “Etude” by Stephen Heller and Margaret the “Momento Capriccioso” by Carl Maria von Weber.

49 Department of Commerce–Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930–Population Schedule [Manhattan].

50 The 1934 New York, New York Marriage Index, Vol. 12, Number 28784 records Amaryllis Nicol and Theodor S. Ruggles as marrying on 14 December 1934.

51 The 1943 New York, New York Marriage Index, Vol. 10, Number 23690 records Amaryllis Nicol and Ury S. Cabell as marrying on 25 September 1943. Based on his United States of America Declaration of Intention [Naturalization Application], No. 507379 filed on 28 October 1941, Cabell was born in Bucharest, Rumania and emigrated to the United States from Montréal, Canada in 1918 under the name of Endoxil Cabell.

52 United States Social Security Death Index, Stephen Cabell, October 1984.

53 If this is the same Cabell photographed by Lynes, then the marriage to Amaryllis was likely a “lavender” one.

54 United States Social Security Death Index, Amaryllis Cabell, June 1987.

55 Georges Rey kindly provided me with a brief family history begun in 2003 and updated in 2022. Rey’s mother, Tamara Nicol Rey Patri (b. San Francisco 1920), was the illegitimate daughter of Robert Allan Nicol and Honora (Nora) Keating. Thus, Amaryllis and Margaret were the half-sisters of Tamara and the half-aunts of Georges Rey.

56 For example: Margot’s article, “Morning in Valparaiso: A Street Scene in Chile” was published in the 22-26 May 1944 issue of Senior Scholastic, Vol. 46, No. 15, page 20; her poem “Don Pablo Neruda” was published in an anthology in 1975 (see Note 60, below); and her unpublished semi-autobiographical novel was titled Her Father’s Daughter.

57 Op. Cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 16 December, 1928, p. 16.

58 Polk’s Directory of Santa Cruz, Watsonville and Santa Cruz County 1925. San Francisco: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1925, p. 85. This Directory listing reads: “Gunderson Arth O (Margt) h48 Walnut av.”

59 Op. Cit. Santa Cruz Evening News, 9 May 1925.

60 Margot de Silva, “Don Pablo Neruda” in Walter Lowenfels, ed. For Neruda, For Chile: An International Anthology, Boston: Beacon Press, 1975, p. 3.

61 Op. Cit. Georges Rey, “Brief Biography.”

What a stupendous piece of research! Thank you for sharing. Sarah Lowe

LikeLike

Thank you for your appreciative comments, Sarah! I’m glad you enjoyed this post, it was fun to research and write.

LikeLike

This was the best read i’ve had in while. I love the dive into Weston, his world, the moment of freedom they all experienced. In ways, California rivalled Paris!

LikeLike

Thanks for your appreciative comments! I love the comparison to Paris. Ah, those Roaring 1920s and beyond here in Lotus Land.

LikeLike

Fantastic article Paula. You haven’t lost your touch. I want to send you an article you may not have seen referencing Edward from a 1929 Die Form article on Film und Foto.

LikeLike