(© Collection of the Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona)

“The utterly famous photographer and the Grand Old Man of the American photographic world, Edward Weston…” — Shoichi Abe, Photo Art [Tokyo], November 1955[1]

Weston’s association with progressive photographic movements was pivotal to his aesthetic growth in the 1920s, and brought him into the sphere of influential German artists and intellectuals. As a result, he is well represented in German and Austrian publications: fifteen known references in Germany and two in Austria.

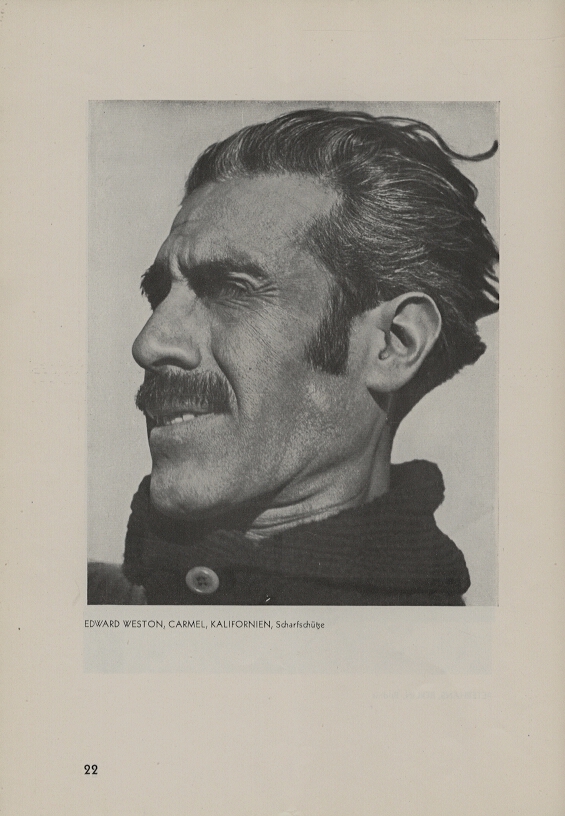

Of paramount importance is Weston’s well-documented participation in the seminal 1929 Film und Foto exhibition in Stuttgart, Germany and its subsequent related venues.[2] As illustrated above, his powerful portrait of Galvan Shooting appears in the catalogue published in conjunction with the February–March 1930 Vienna venue, Internationale Ausstellung: Film und Foto Wanderausstellung des Deutschen Werkbunds.[3] Unlike the original Stuttgart exhibition, with twenty Weston photographs, Vienna included only eight.

Surprisingly, the first published German reference precedes Film und Foto by three years. On 21 November 1926, Der Welt Spiegel (the Sunday supplement of the liberal newspaper, Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung), featured Weston’s Pipes and Stacks: Armco, Middletown, Ohio on its cover, the result of a request from “Herr Klötzel,” a Berliner Tageblatt representative who Weston had met in Mexico. Unfortunately, there is no related article and, grievously, Weston is not credited. The cover notes only: “PHANTASTIK DES ALLTAGS / Abzugsschlote einer Fabrik in Ohio, die wie gigantische Orgelpfeifen wirken.” [Everyday Fantasy / Chimneys at an Ohio factory that look like gigantic organ pipes.”[4]

Pipes and Stacks, Armco also appeared in Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s 1929 book, Von Material zu Architektur, again without crediting Weston.[5] Moholy-Nagy must have obtained his print from Der Welt Spiegel, not Weston, as indicated by the illustration caption: “abb. 202 abzugsschlote einer fabrik in ohio foto: weltspiegel.” [factory chimneys in Ohio photo: weltspiegel]

One of the most unexpected instances of a German publication drawing upon Weston’s work is this little known pictorial in the November 1931 issue of Die Dame, a progressive monthly magazine geared towards the sophisticated, modern German woman. Published in Berlin by Ullstein Verlag, it concentrated on fashion, art, literature and other topics of interest to the “new woman.”[6] How these two Weston photographs came to be included in Die Dame is a mystery I am still attempting to unravel. The entire November 1931 issue was examined on microfilm, but no hints as to the “who and how” of this Weston connection were found. Nor were either of these photographs known to have been included in a European exhibition at the time. Of course, Weston had numerous friends in and/or associated with Germany, among them Hildebrand Gurlitt, Tina Modotti, Richard Neutra, and Galka Scheyer, as well as German contacts from his time in Mexico. Perhaps it was one of these connections who brought Weston to the attention of Die Dame.

From Germany we travel to Holland, where eight publications, all related to exhibitions, have been located. The earliest dates to 1922: a review of the Ninth Annual Exhibition of Photographs that appeared in Volume 9 (no month stated) of the periodical, Focus: Fotoblad Voor Groot Nederland, the “official organ” of the Dutch Amateur Photographers’ Club.[7] A Weston portrait of Johan Hagemeyer (Conger 73/1921) is illustrated. A critique of the California photographers, including Weston, reads (translation supplied by Hans Rooseboom, Curator of Photography at the Rijksmuseum):

From three Californian contributors there is a handful of photos that are curiosities [in the sense of worth seeing] in themselves. We do not doubt that many an honest Dutch fellow will put on a doubtful face if he sees such a queer photo like No. 222, ‘The Hands of Robelo’. These are the very expressive hands of someone who is in the act of speaking, including just a tiny part of the man’s chin. It seems very odd, but it is really witty and it just does what it should do. / Further there is a double portrait of Joh. Hagemeyer and Edward Weston, also such a strange thing. The heads cut right in half, but if you paste the rest of the heads, it will become conventional again. This Hagemeyer is a clever guy, not only in his judgment of women (his own portrait is there as well), but also as a photographer. Take a look at what he made of such subjects as No. 233 (‘Emigrants’), No. 234 (‘On deck of the Metagama’) and No. 235 (‘Steam crane’). What a nearly repulsing, unimportant subject, and what has this man, who rightly saw the beauty of it, been able to do with it. This picture we will publish in a forthcoming issue. / Very queer figure studies, some perhaps somewhat overdone to the judgment of the present writer’s Dutch taste, but yet original, are brought by Ed. Weston, who, among other things, was able to make very picturesque fragments of nudes into complete poems of beauty. His various variations of figures in corners of attics, are somewhat affected, with all respect to the witty invention, but nevertheless instructive.

The final Dutch publications in this post are catalogues from exhibitions held in 1950, 1952 and 1958. The first is Internationale Tentoonstelling vak Fotografie 1950. Organized by Martiens Coppens at the Stedelijk Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven, it included ten Weston photographs.[8]

A typewritten invitation, dated 4 October 1949, from Coppens to Weston, located in the Edward Weston Archive at the Center for Creative Photography, reads in part:

… In March 1950 a congress will be held by the United Dutch Professional photographers. The most important part of same will consist of an exhibition of work, contributed at our request, by about 30 of the world’s leading professional photographers. / The aim of the exhibition is to give an impression of ‘The New Vision’ in photography. Seeing that you enjoy an excellent reputation as a modern photographer, we were very pleased to place your name on the list of those invited. / Daniel Masclet, Paris, with whom we got into touch regarding the photographers to be invited, put 4 crosses behind your name to express his admiration, whilst with the other names he did not get any further than 3. Further, he made the remark: ‘Le plus grand photographe du mond!!’ / When inviting you we understand your objections: Holland is a small country and so far away. Still, I should like you to know that there is a good deal of enthousiasm [sic] and interest in our small country for the expression of modern photography. We should therefore feel much obliged if you would send us some of your photos.[9]

The 1952 exhibition, Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel: Internationale Fototentoonstelling, also organized by Coppens at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, included twenty-five Westons.[10]

We conclude with the 1958 catalogue from the final venue of the traveling exhibition, Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel: Foto-tentoonstelling 1957-1958 [Photography as an Expressive Medium].[11] Weston exhibited ten photographs in this show. Frustratingly, the checklist provides dates but not titles, although, as indicated by the catalogue illustration below, the single photograph listed from 1941 was clearly Grand Canyon.

Journeying to nearby Denmark, we find two interesting publications with Weston content. Not surprisingly, the earliest, from 1920, relates to an exhibition: the catalogue to the Copenhagen Photographic Amateur Club Exhibition: American Section, held from August–September 1920.[12] Six Weston photographs are listed on the back page of this exhibition checklist.

Also from Denmark comes one of the most unexpected international publications with Weston content: an outstanding, two-page article, replete with seven illustrations, in the 5 June 1932 issue of Politiken Magasinet, the Sunday magazine section of the Copenhagen newspaper, Politiken.[13] (See footnote for a translation of the lengthy article.)

Discovering this gem is a tale of research serendipity. In the Carmel Pine Cone, I came upon the following tidbit in the “Studio Gossip” column on 1 July 1932[14]: “Edward Weston has just had a two-page write-up with eight reproductions of his photographs in the Copenhagen Politiken. His reputation is growing constantly. Even the Scandinavians have heard of him. / He has just returned from the south where he has spent a fortnight visiting his sons in Santa Barbara and Santa Maria. And he casually mentioned that in the fall he expects to publish a book on his work. This is interesting news. One cannot help but realize that a book of this type from such an authentic source will be seized upon eagerly by students of photography and the disciples of Weston.” [NOTE: The Politiken article is actually illustrated with seven Weston photographs, not eight.] Paul Hertzmann’s tenacity enabled him to locate and acquire an original copy of this outstanding issue of Politiken. Great sleuthing all round.

Our international tour concludes by traveling half-way around the world to Japan and China. Ten publications, all from the 1950s, hail from Japan. The earliest is the catalogue to an important 1953 circulating show titled Exhibition of Contemporary Photography—Japan and America. Co-organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, this exhibition appeared in Tokyo and Osaka between August and October and included six Weston photographs.[15]

The Tokyo venue engendered a flurry of reviews in local newspapers. Transcriptions of six reviews (five of which mention Weston) may be found in the Museum of Modern Art Archives.” Here is one example from the 27 August 1953 issue of the newspaper Tokyo Shimbun:

The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo presents an exhibition of contemporary photography. The increasing enthusiasm for photography in post-war Japan has led to a higher regard for the importance of photography on the part of a greater number of Japanese. The Museum, considering photography a field of modern fine art, seeks, by means of this exhibition, to display its potentiality as a medium of artistic expression; to show how photography is used in science, in commerce, in industry, in juridical investigation, in journalism; and to demonstrate its indispensability as a tool for the recording of fact and reality in the world of today. / The exhibition consists of about 100 of the most representative examples of contemporary American photography and about the same number of Japanese photography, displayed on a comparative basis. The American collection was selected by Mr. Edward Steichen, the Director of the Photography Department of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Japanese collection was selected by Messrs. Takaho Itagaki, Nobuo Ina, and Shigene Kanamuru. / Mr. Imaizumi, the Assistant Director of the Museum, says: ‘Generally speaking photography is based on realism. But I was much interested in seeing that American photographers are veering toward abstraction and surrealism. On the other hand, I note that realism is exerting great influence on Japanese photographers. In their pursuit of realism, however, the Japanese photographers have produced work that is no less meritorious than that of the foreign photographers – a fact that is particularly remarkable in view of the fact that Japanese photographers have not yet entirely recovered form the war slump. I hope this exhibition will be of some use to them.’ / Accompanying the exhibition a U.S.I.S. film: ‘Edward Weston,’ is to be shown in the Museum auditorium twice every afternoon except Mondays. Messrs. Ihei Kiura, Shigene Kanamuru and Nobuo Ina will speak on photography during the period of the exhibition.[16]

Two interesting non-exhibition related Japanese publications round out our time in Japan. The first is an excellent article by Shoichi Abe in the November 1955 issue of Photo Art [Tokyo].[17] Titled “Edward Weston’s Work and Technique,” this well-illustrated essay reproduces five Weston photographs and a portrait of Weston by Morley Baer. In addition to outlining Weston’s career and techniques, Abe compares Japanese photographic practices with those of Weston. The article reads, in part, (translated from the Japanese by Yuko Fukami, Berkeley, California):

The utterly famous photographer and the Grand Old Man of the American photographic world, Edward Weston, celebrated his 69th birthday this year. He continues to be active despite his advanced age. He began as a humble, everyday photographer, and moved to Mexico where he became absorbed in producing artistically motivated pieces while keeping company with progressive local painters and encouraging their work. The famous ‘f64 Group’ was founded in 1932, … / During this period Weston employed a keen method of expression where he treated his subjects as close-up objects. By portraying the real shape and texture of his subjects using the smallest aperture, he managed to depict the elemental characteristics of his subjects. … / Weston’s life as a photographer has reached 50 years but he is still energetically engaged in his activities without having changed the fundamental leanings of his work. In Japan, a film that chronicled his creative process, ‘Edward Weston: The Photographer’ was shown after the war, and he remains a familiar figure of photography in our country. … / … Weston’s cameras used regularly are all large-format cameras such as the 8×10-inch view camera and the 4×5-inch Graflex camera, which are hard to find in Japan. … He always uses pyro or pyro-soda developer, an almost forgotten developer of the past, and amidol for developing photo paper. This seems very strange from the current state of the photographic world where photographers are feverish about sensitized [or intensifying] developers and fine grain developers. But since Weston uses large-size negatives that are bigger than 3 1/2 x 4 1/2 inches, it doesn’t need large magnifications … and in the case of the 8×10-inch view camera, no enlargement is required as he only makes contact prints. … The combination of pyro developer (for film and dry plate) and amidol (gaslight paper) was used widely at one time in Japan, and there was a period when it was considered to be a kind of ‘common sense’ among photographers. Weston has continued to use this common sense from the 50s in his work, which is based on his own theory, ‘[a photographer] should select the film, the paper, and the developer that best suits him, master them, and stick with them.’ It is quite interesting to see a number of photographers similar to Weston in America (for example Rothstein). American photographers often use view cameras, in contrast to our country. Japan’s photographic world, whose character is often follow blindly, could learn a lesson or two from this. / … / The greatest American photographer Edward Weston continues to work today. A lot is expected of what he will produce in the future. …

The final Japanese publication with substantive Weston content is the 1957 book, Sekai Shashin Zenshu. Photography of the World. America I to which Nobuo Ina contributed an extensively illustrated segment titled, simply, “Edward Weston.”[18] Ten Weston photographs, including one 1947 color photograph, Desert-tanned Boot, and a portrait of Weston by Glen Fishback, are reproduced. Titles and descriptive text appear on separate pages from the illustrations themselves. The following two samples reflect a sense of the Japanese author’s response to Weston (translated from the Japanese by Yuko Fukami, Berkeley, California):

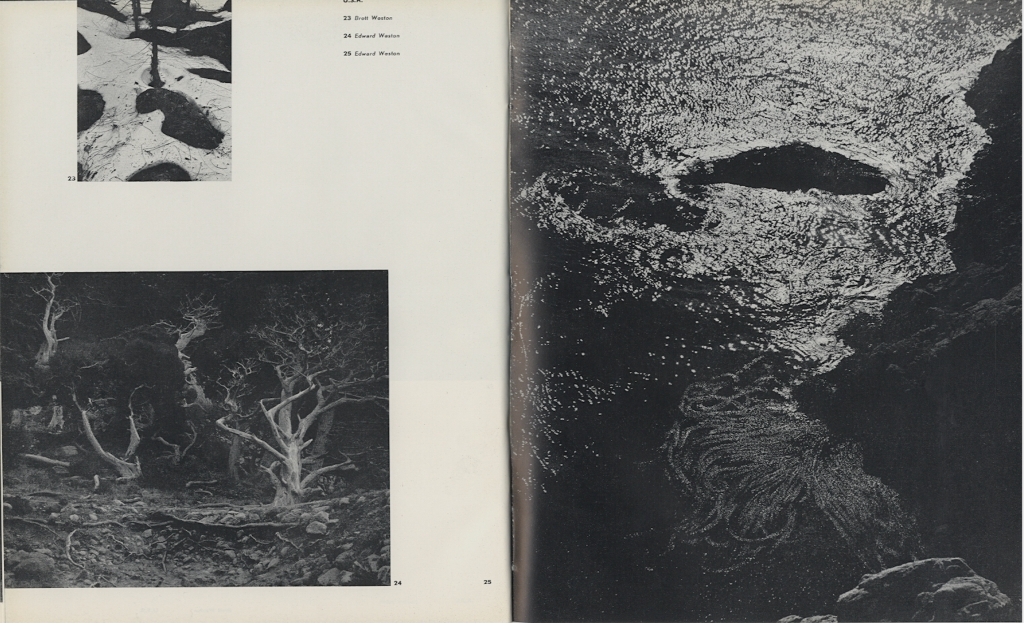

Plate 25, Uprooted Cypress, Point Lobos: “25 Cypress, Uprooted: It was after Weston moved to Carmel in 1929 and started to tackle Point Lobos in earnest that he began to show interest in branches and roots of the cypress tree. ‘I did not try to shoot rocks and vast scenery. I tried the cypress tree. I tried the details and the section of its branches and roots. Brett and Merle Armitage screamed after seeing the negatives. Merle said that there was ‘a cypress that looked like a flame,’ he wrote in his Daybook on March 21, 1929. This root of a dead cypress has an otherworldly beauty, which was created by the great forces of Nature. The strength of the tree’s life force that fought Nature’s forces can be sensed from the photo. From 1934. (Nobuo Ina).”

Plate 24, Artichoke Halved: “24 Artichoke, Cut in Half: A piece from 1930. The group of vegetable photos that Weston produced contains photos of such things as cabbage leaves and this. People were unaware of the life force of plants until Weston discovered it as beautiful lines. He said, ‘The lay public will scream in surprise, because they’re seeing it for the very first time through an artist. The artist becomes the interpreter and an intermediary.’ Not only Weston, but all of the work by good artists are that way, but I think those words especially befit this piece. (Noruo Ina).”

The final stop on our Weston sojourn is China, where the only published reference I have found is a postcard announcing an exhibition of his work in Shanghai in May 1933.[19] Weston commented on this in his Daybook entry of September 15, 1933[20]: “Besides my Chicago exhibition I got together 50 prints—old extras—for Lita Coughlin to take with her and show in Shanghai; …” Other than this note, the Shanghai exhibition remains a mystery. How was it received in China? Who, if anyone, acquired photographs from this show and where are those photographs now?

Our 21st century perspective allows us to unhesitatingly acknowledge Weston as a world-class master of the photographic medium. So it is fascinating to read the responses of international audiences experiencing his work, often for the first time, in the early to mid-20th century. When, in 1914, Weston proclaimed himself a photographer “with an international reputation,” could he have possibly foreseen the acclaim his art would garner around the globe? Fortunately, Weston was well aware of the publications, exhibitions and accolades reflected in this blog. How fortuitous that he lived to see his reputation so emphatically and universally established.

NOTES

1 Shoichi Abe [or Seichi or Masakazu], “Edward Weston’s Work and Technique,” Photo Art [Tokyo] 7:15, November 1955, 29–33, 115–116.

(Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Publications Box 31)

2 The Deutschen Werkbunds, Internationale Ausstellung des Deutschen Werkbunds Film und Foto in Stuttgart, Germany was held from 18 May–7 July 1929. Stuttgart was the original venue for this exhibition which traveled, in revised form, to Zurich, Switzerland, 28 August–22 September 1929; Berlin, Germany, 19 October–17 November 1929; Danzig, [Poland] 1929, dates unknown; Vienna, Austria, 20 February–31 March 1930; Zagreb, Croatia, 5–14 April 1930; Tokyo, Japan, April 1931; and Osaka, Japan, 1–7 July 1931. Note: I have not verified the inclusion of Weston photographs in Zurich, Danzig, Zagreb, Tokyo, and Osaka.

3 Internationale Ausstellung: Film und Foto Wanderausstellung des Deutschen Werkbundes, Vienna: Michael Winker, n.d. [1930]. [1 Illustration; 8 checklist entries]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

4 “Phantastik des Alltags,” Der Welt Spiegel [Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung Sunday supplement] [Berlin], 21 November 1926, Cover. [1 Illustration]

(Microfilm obtained through Inter Library Loan at the San Francisco Public Library)

Weston commented on this commission in his Daybook entries for 30 September 1926 and 11 August 1927:

30 September 1926 (Daybooks, Vol. I, Mexico, p. 192): “A representative of the Berlin Tageblatt wants to reproduce a number of my photographs, but how to spare time for making prints, I question. I am so ‘fed up’ on this work I am doing. I go to bed thinking negatives, prints, failures, successes, how many done, how many to do — and awaken with the same thoughts.”

11 August 1927 (Daybooks, Vol. II, California, p. 35): “My meal ticket this time came from Germany, a check for $20 from the Berliner Tageblatt. Somehow it made me unusually happy, and something sang within, —the check was unexpected. The amount was small for four prints, but the newspapers in the States expect donations,—the privilege of seeing one’s name in print is supposed to be enough! / And the Tageblatt has asked for more prints. / I had confidence in Herr Klötzel when I gave him these photographs a year ago in Mexico, and I was not mistaken.”

5 Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Von Material zu Architektur [From Material to Architecture] Bauhausbücher 14. Munich, Germany: Albert Langen Verlag, 1929. [1 Illustration]

(Collection of the Universitäts-Bibliothek, Heidelberg, Germany)

6 “Die Natur schafft Bildwerke” [Nature creates sculpture], Die Dame 59:4, November 1931, 38. [2 Illustrations]

(Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; Scrapbook A)

7 Adriaan Boer, “De Negende Jaarlijksche Salon,” Focus: Fotoblad Voor Groot Nederland 9, 1922, 252-255. (1 Illustration)

(Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands)

8 Martiens Coppens, Internationale Tentoonstelling vak Fotografie 1950, Stedelijk Van Abbe Museum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1950. [1 Illustration; 10 checklist entries]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

9 Typewritten letter from Martiens Coppens to Edward Weston; Stedelijk van Abbe-Museum letterhead, dated 4 October 1949. (Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Box 35, Folder 17)

10 Martiens Coppens, Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel: Internationale Fototentoonstelling, Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, [1952]. [2 Illustrations; 25 checklist entries]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

11 Martiens Coppens, Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel [Photography as an Expressive Medium]. Gravenhage [The Hague], The Netherlands: Gemeentemuseum, [February] 1958. [10 Checklist entries]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

Gravenhage was the final stop for an exhibition that opened at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 28 September–27 October 1957 then traveled to the following venues throughout The Netherlands from 1957–1958: Groningermuseum, Groningen, 9 November–8 December 1957; Gemeentemuseum, Arnhem, 21 December 1957–2 February 1958; and Gemeentemuseum, Gravenhage [The Hague], 8 February–23 March 1958.

12 Copenhagen Photographic Amateur Club Exhibition 1920: American Section, No location, no publisher, 1920. [6 Checklist entries]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

13 Louise Bjørner, “Naturen Som Billedhugger” [“Nature As Sculptor”], Politiken Magasinet [Copenhagen] 2:22, 5 June 1932, n.p. [14–15]. [7 Illustrations]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

Art historian Thor Mednick translated this article for us as follows:

Nature as Sculptor / It has often been suggested – and with some truth – that America has not brought forth an art of its own since the Whites became masters of the land. Painting and sculpture have been emulations of the various European schools, and there have been no crafts to speak of, excepting the rugs that Indians make for tourists. / America has made its mark in literature, however, and masterworks of architecture have been achieved that are just as beautiful and distinctive as the Egyptian Pyramids. American skyscrapers resemble nothing else on Earth, and yet they are not products of fantasy, but created of necessity, because the premium placed on fast and efficient business requires centralization within already quite limited areas of land. / A ‘Technical’ Artist / It is fitting that here in the land of machines a man has emerged who, with the help of a camera, has discovered a new pictorial effect that reveals the objective beauty of things [that is, things as objects – perhaps, ‘simple things’ or ‘things themselves’ or ‘things as things’?]. Edward Weston is this man. / He is 100 percent American. His ancestors were among the very first immigrants to settle in America. Weston himself was born and raised in Chicago, the city of butchers and canners. His father was a surgeon, his grandfather a poet, and it is as though these two spirits live on as one in his being. Edward Weston received his first camera at the age of sixteen. He was immediately taken with the work of photography, wandering from house to house, from neighborhood to neighborhood, photographing everything from weddings to seaweed washed up on the beach. / Peculiar Formations / His pictures got progressively better. The following years saw a steady stream of prizes, diplomas and commendations from both America and abroad. One day, however, he chucked them all, claiming that he had received them for achievements he did not care much about anymore. He pulled up stakes and left for Mexico, where he was quickly drawn to the renaissance in painting taking place there. Along with Rivera, Charlot, Orozzo, and many others, Weston ushered in a new era in the history of art. / Eventually, Weston settled in California: in the little artists’ colony of Carmel, on the coast between San Francisco and Los Angeles. There, Weston found his ideal workplace and took the pictures that are featured this month in his second New York exhibition: these peculiar photographs that cause people to stop in their tracks and wonder aloud, ‘Is it Futurism, Symbolism, a tonal fantasy, fairy tale illustration, or what?’ / ‘None of these,’ answers the artist. ‘They are photographs of reality, without retouching, without staging, without artificial light or any other such humbug. Anyone who looks around can find any number of similar stones, shells, mushrooms, pieces of wood, piles of seaweed, et cetera. All forms and lines can be found in existence. No artist has ever introduced anything new. And it would be impossible to do so, anyway, because we we cannot go beyond life’s limitations or parameters. All is given, we have only to receive.’ / Thus, Edward Weston has no program, as such – he does not want any kind of ‘ism’ attached to him or his work. In his view, an art that results in a particular school or direction is dead on arrival: it atrophies in the frame. ‘We should not attempt to perfect Nature, but rather strive to reveal it. And to that end, the photographic lens [Edward Weston’s only cost five dollars] is a sure and objective aide when used with insight and patience.” [that bracket is actually part of the quote – appears, as such, in the original.] For a long time, he took pictures of snail shells; he was taken with their dimensions, their refractions of light, the strange effects of their surfaces. ‘They look like orchids,’ say viewers, taken with their strange magnificence. ‘It’s just plain and simple snail shells on a piece of writing paper,’ laughs the artist. In another period, he took pictures of bananas, toying with and manipulating them in a quest for the right view. That continued, until the day his sons freed him from such problematic experiments by eating the bananas! / Edward Weston searches for the most stringent objectivity in all of his motifs. He doesn’t just present the form and the light; one gets a palpable sense of the material: the tree seems rugged, the snail shell fine and beautiful, the seaweed wet and slimy, the stone cold and hard. For a Dane, it is natural to think of H.C. Andersen, and while H.C. Andersen was not quite as subjective in his interpretations as Edward Weston is objective, the moral of Andersen’s story, “The Bell,” echoes strongly in Weston’s work, although the two came to their marvelous revelations by markedly different paths. A bell-pepper of Weston’s looks exactly like a grumpy, grey-bearded troll; pebbles, lying in the mid-day sun on a little stretch of beach, seem like little tots out for a walk. An egg-slicer [for 25 øre (one-quarter Danish Crown, i.e., cheap)] becomes an apotheosis of machine engineering. Edward Weston smiles at our surprise. Nothing is further from his mind than to present things as anything other than what they are. / A Visit with Edward Weston / We walk together through his atelier in Carmel. It’s as plain and peaceful as a priory cell. He shows me his treasures, thick portfolios full of the fruits of many years’ work. ‘This is what I live for,’ he says, ‘and those,’ he points to some portraits on the wall, ‘are what I have mainly been living on. When it comes to people, I have sometimes had to make a compromise. One has to live, after all.’ / But one realizes quickly that those people who go to Edward Weston don’t come to be made pictorially beautiful. They come to get a faithful rendering of themselves for posterity to remember them by. And he allows that amusing wart to stay where it is, allows that authoritative woman to retain the down on her lips, and shows us the wisdom in an old, wrinkled face. He who has a soul always ages beautifully – only the soulless become ugly. / Outside the window, the peaceful ocean rolls in long, smooth drafts toward the rocky shore. On the cliff, stripped and weather-beaten cypress trees stand at a tilt and stretch their white branches in toward the land. Edward Weston is the only one of the colony’s artists, however, who never worshipped those cypresses – like H.C. Andersen, he showed the world greatness and wonder in little, mundane things. / Louise Bjørner.

14 Marjorie Tait, “Studio Gossip,” The Carmel Pine Cone 18:27, 1 July 1932, 7.

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

15 The Exhibition of Contemporary Photography—Japan and America 1953 [aka Contemporary American Photography] was organized by the Museum of Modern Art, New York International Program in collaboration with The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. The American photographs were selected by Edward Steichen. The exhibition opened in Tokyo, 29 August–4 October 1953 with subsequent travel within Japan to the Fuji Film Building in Osaka, 12–18 October 1953. It then traveled in Europe, with additions and substitutions, as the photography section of a show titled Modern Art in the United States. The European venues were: Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, Paris, France, 30 March–15 May 1955; Kunsthaus, Zurich, Switzerland, 16 July–28 August 1955; [Sent to United States Embassy, Oslo, Norway following Zurich venue, but never shown]; Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, The Netherlands, 2 March–15 April 1956; Neue Galerie, Linz, Austria, 5 May–2 June 1956 (Photography section shown separately in Linz; painting, sculpture, print and architecture sections of Modern Art in the United States shown in the Secession Galerie, Vienna); ULUS Gallery, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 6 July–6 August 1956 (Photography section shown with print section in ULUS Gallery; painting and sculpture section shown in Kalemegdan Pavilion; architecture section shown in Fresco Museum).

16 [Review of The Exhibition of Contemporary Photography—Japan and America 1953 at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo] Tokyo Shimbun, 27 August 1953, page unidentified.

(This and four additional reviews are located in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Archives, “Japanese Press Reaction to Contemporary American Photography”; File V.ICE-F-13-53.2)

17 Shoichi Abe [or Seichi or Masakazu], “Edward Weston’s Work and Technique,” Photo Art [Tokyo] 7:15, November 1955, 29–33, 115–116. [6 Illustrations]

(Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; Publications Box 31)

Each of the photographs illustrated is accompanied by a caption which describes the photographic and printing techniques Weston used to make it.

18 Nobuo Ina, “Edward Weston” In Sekai Shashin Zenshu. Photography of the World. America I, Tokyo: Heibonsha Publishers, 1957. [Refs. pp. 48, 53–55. 11 Illustrations]

(Collection of the Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University)

This book proved exceptionally difficult to locate. I finally tracked it down to the Gotleib Archival Research Center at Boston University, which, according to WorldCat, is one of only two libraries that own it (the other is in Switzerland). The Gotleib Archival Research Center was gracious enough to send me photocopies of the Weston related portions.

19 [Exhibition Announcement] [International Arts Theatre], The International Arts Theatre Announces an Exhibition of Prints By Edward Weston… Shanghai, China: International Arts Theatre, May 1933. [Postcard] (Collection of the Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; Scrapbook A)

20 Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, vol. 2, California, ed. Nancy Newhall (Millerton, N.Y.,1973), 276.