“When an artist begins to sign his work it is indicative of a certain self-esteem, self-consciousness.”[1]

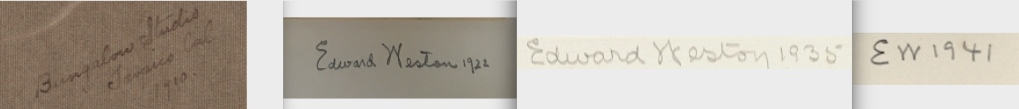

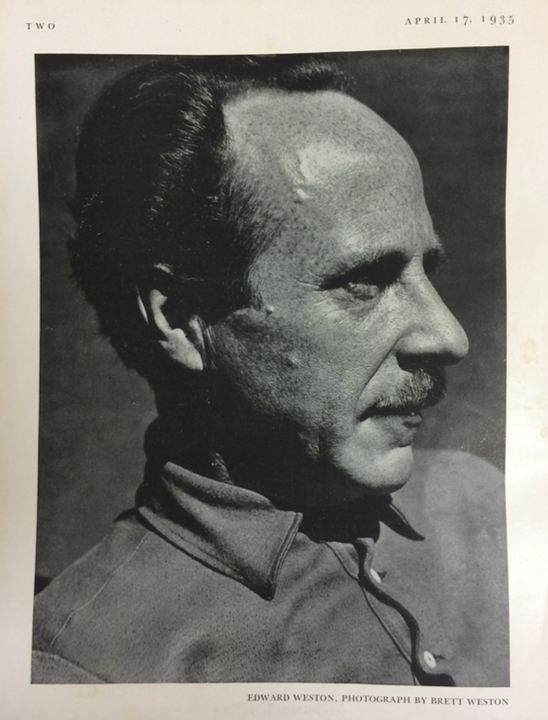

Throughout his career Edward Weston reinvented his signature to align with his artistic evolution and the broader aesthetics of his times. As he progressed from a young Pictorialist “aesthete” in the 19-teens to an emerging Modernist in the 1920s and, finally, a consummate photographer in the mid-1920s through the 1940s, his signature transformed to reflect his self-image as an artist, the compositional character of his work and even, at the end, his deteriorating health. This post presents a representative sampling of signatures spanning the full range of Weston’s highly creative and productive life.

NOTE: Unless stated otherwise, all photographs illustrated in this post are currently owned, or were owned in the past, by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc. All photographs © Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

The Early 1900s

“Dear Papa, / Received camera in good shape. It’s a dandy. I think I can work it all right. Took a snap at the chickens.”[2]

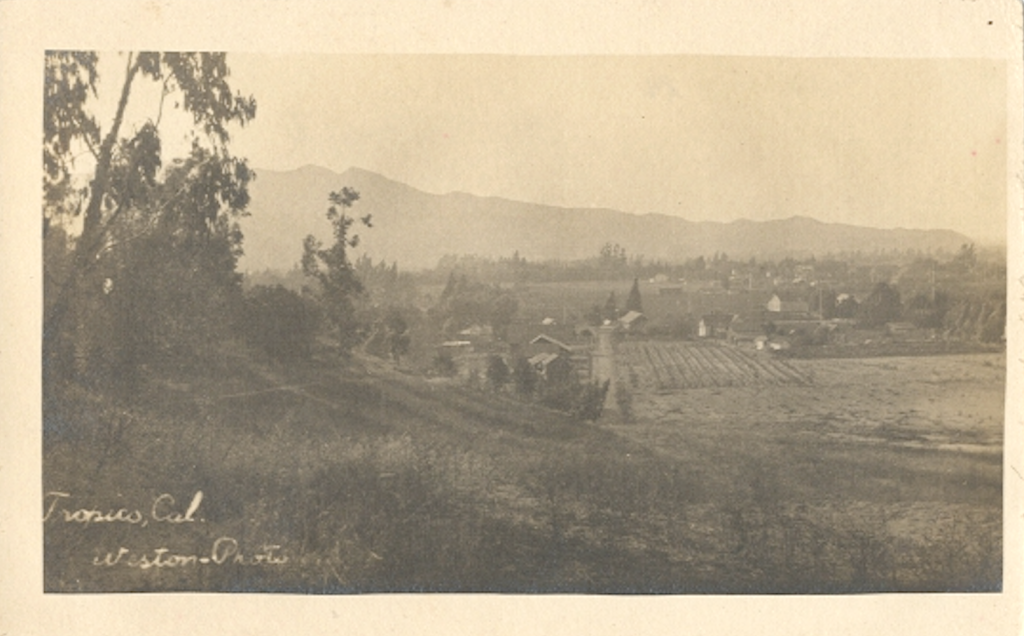

This real photo postcard from 1907 (Not in Conger) marks Weston’s recent arrival in California (May 1906) and the beginning of his professional career.

As befits the commercial nature of his earliest work, Weston relies on a cursive, signed-in-the-negative notation that reads simply: “Tropico, Cal. / Weston-Photo.” It omits his first name, initials, middle name, and studio. At this time he was seeking to build a reputation as a fine art photographer while simultaneously earning a living as a railroad surveyor, an itinerant photographer, and finally an assistant in the Los Angeles studios of George Steckel and A. Louis Mojonier. Despite his early peripatetic employment, by 1906 Weston’s work was already recognized in photographic magazines.[3] Yet the reality of owning his own studio remained four years in the future.

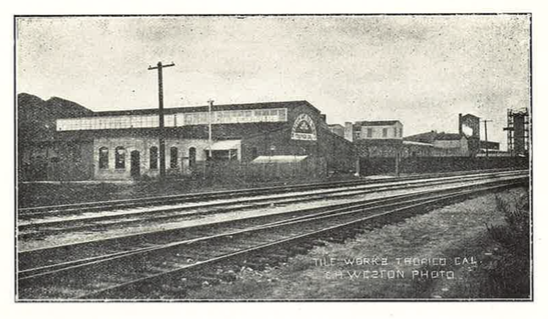

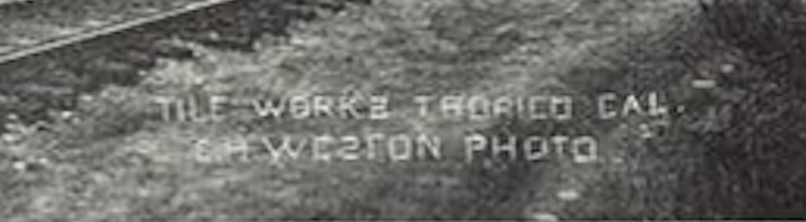

A similar in-negative signature appears occasionally in Weston’s subsequent commercial work. This image of the Tropico Tile Works (Not in Conger) is one of many Weston photographs illustrated in the promotional booklet, Glendale California: The Jewel City [1912]. Here, Weston clearly identifies the subject and himself in straightforward, all caps, block printing. But note the mistake he made with the “s” in “Works” and “Weston”: they’re reversed!

as illustrated in Glendale California: The Jewel City [1912], p. [34] [Glendale Public Library]

The 19-Teens

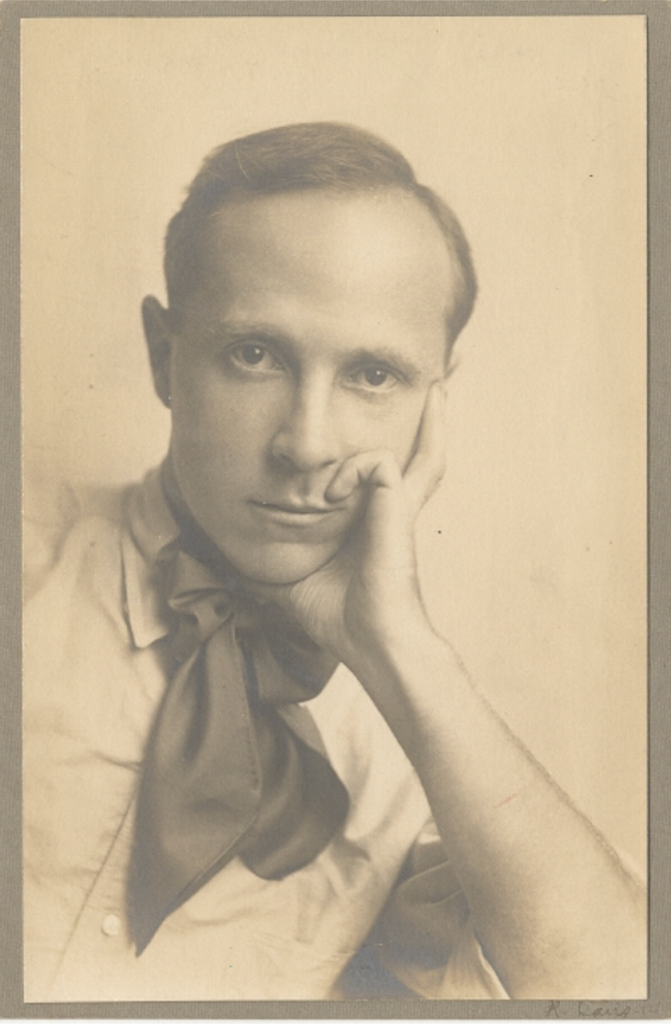

“… That whole soft focus period in retrospect seems like a staged act; I even dressed to suit the part: windsor tie, green velvet jacket—see, I was an artist!”[4]

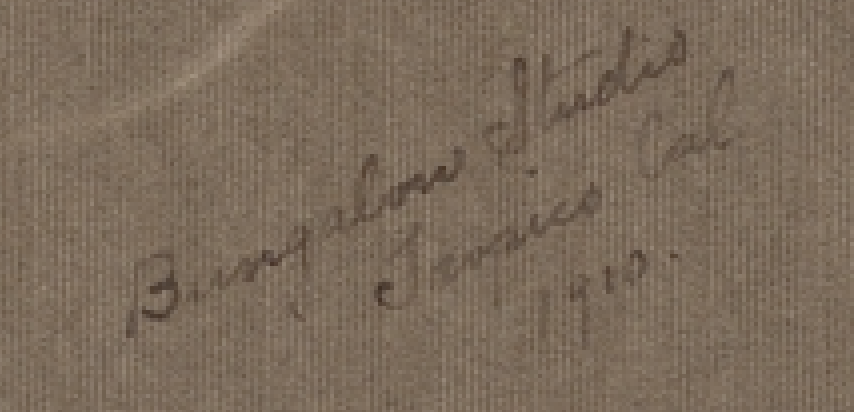

Weston opened his first Tropico studio, the “Bungalow Studio,” in July 1910[5] and it wasn’t long before clients seeking quality portraits began to arrive. In this charming 1910 image of three-year old Lois Oliver (Not in Conger)—certainly one of his earliest Bungalow Studio photographs—Weston adopts an appropriately formal, handwritten cursive signature on the mat, recto. Curiously, he identifies the studio, but not himself.[6]

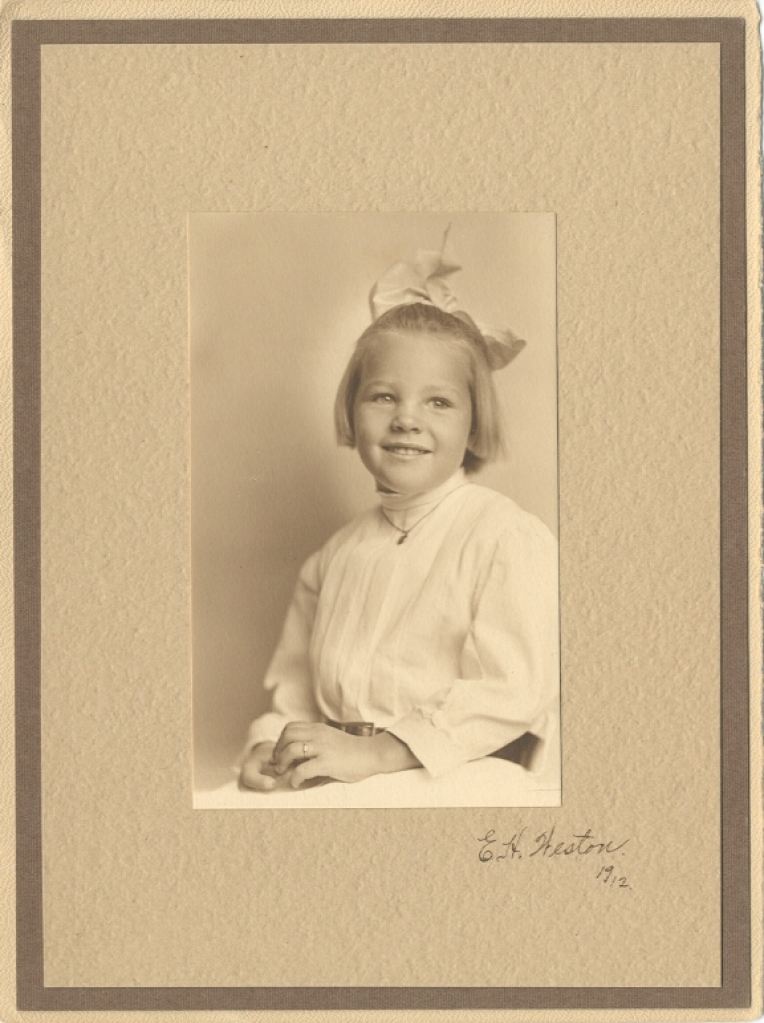

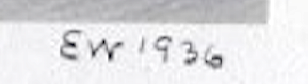

Two years later, in a subsequent portrait of Lois Oliver (Not in Conger), Weston identifies himself rather than the studio in a handwritten cursive signature on the mat, recto that reads: “E.H. Weston. / 1912.” The switch from studio name to his own most likely reflects his growing name recognition.

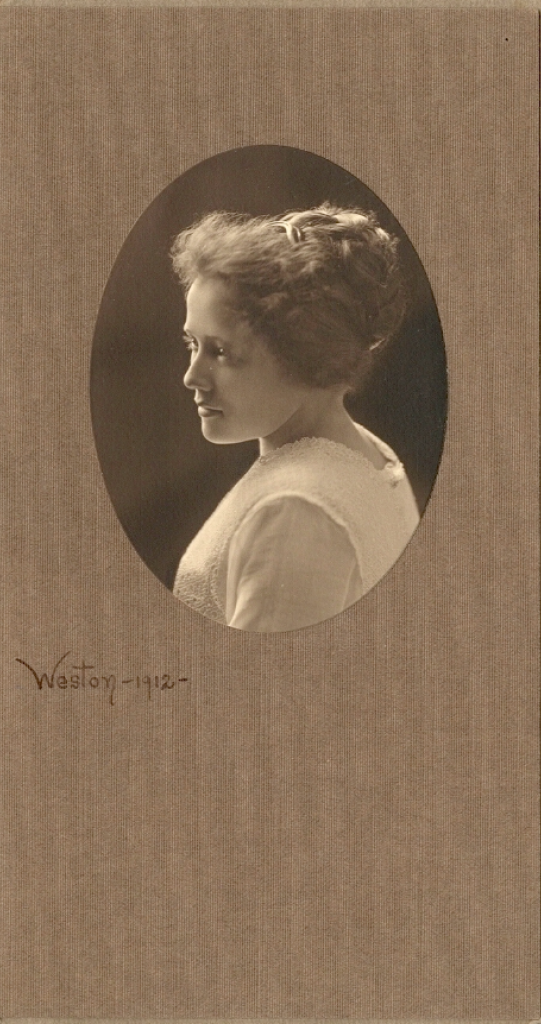

The same year, he experiments with a variant signature: a simplified, clearly printed (albeit with an exuberant “W”) “Weston–1912–,” as seen on the mat, recto, of this Portrait of an Unidentified Woman (Not in Conger).

Another fresh signature appears on the mat, recto, of this 1913 portrait of a lovely, unidentified, young woman. As with the 1910 Bungalow Studio signature on the portrait of Lois Oliver, Weston sets his name on a dynamic diagonal rather than a more static horizontal. Whether intentional or not (I suspect it is intentional), this placement repeats the diagonal slope of the woman’s torso, thereby using both the composition and the signature to emphasize her direct and penetrating gaze.

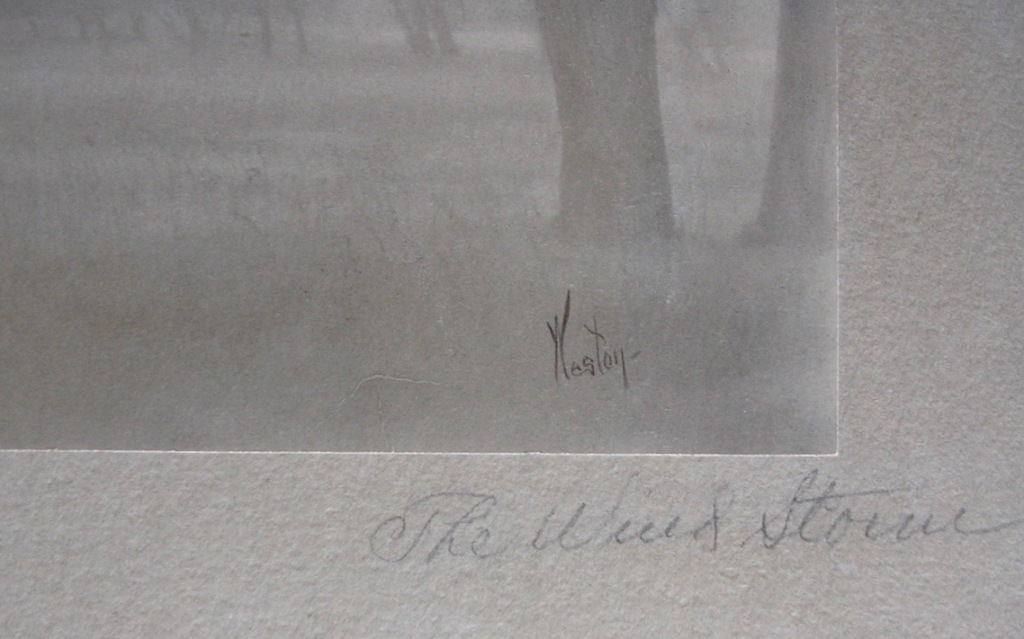

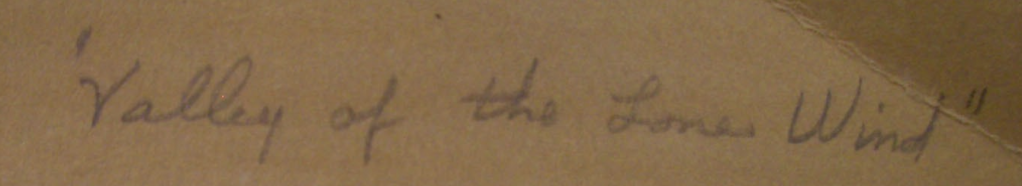

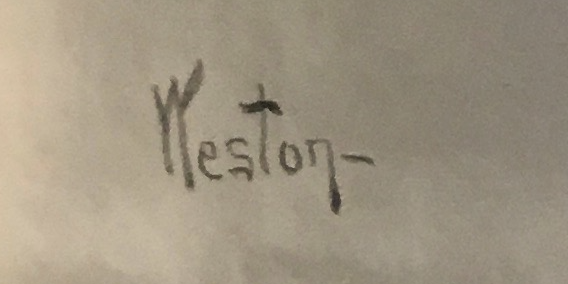

A significant departure in 1913 is the manner in which Weston utilizes his signature on the masterful pictorial photograph, Gaunt, Driven Boughs in the Sweep of Open Wold [aka Valley of the Long Winds aka The Wind Storm aka Valley of the Lone Wind] (Not in Conger).

This is no commercial effort meant to please a client. It is a personal expression intended for critical appraisal by fellow artists through exposure in major photographic salons. Accordingly, Weston adopts the self-assured signature: “Weston,” conveyed with a dynamic “W” and a vigorous, diagonally crossed “t.” Equally important is the placement of the signature at the lower right on the print itself, which effectively inserts Weston into the photograph. Indeed, the sweep of the “W” and diagonally crossed “t” echo the arching tree boughs, transforming Weston’s name into a compositional element. Weston inscribed two titles on the print illustrated here: one on the mount recto, reads “The Wind Storm”; the other, on the mount verso, reads “Valley of the Lone Wind.”[7]

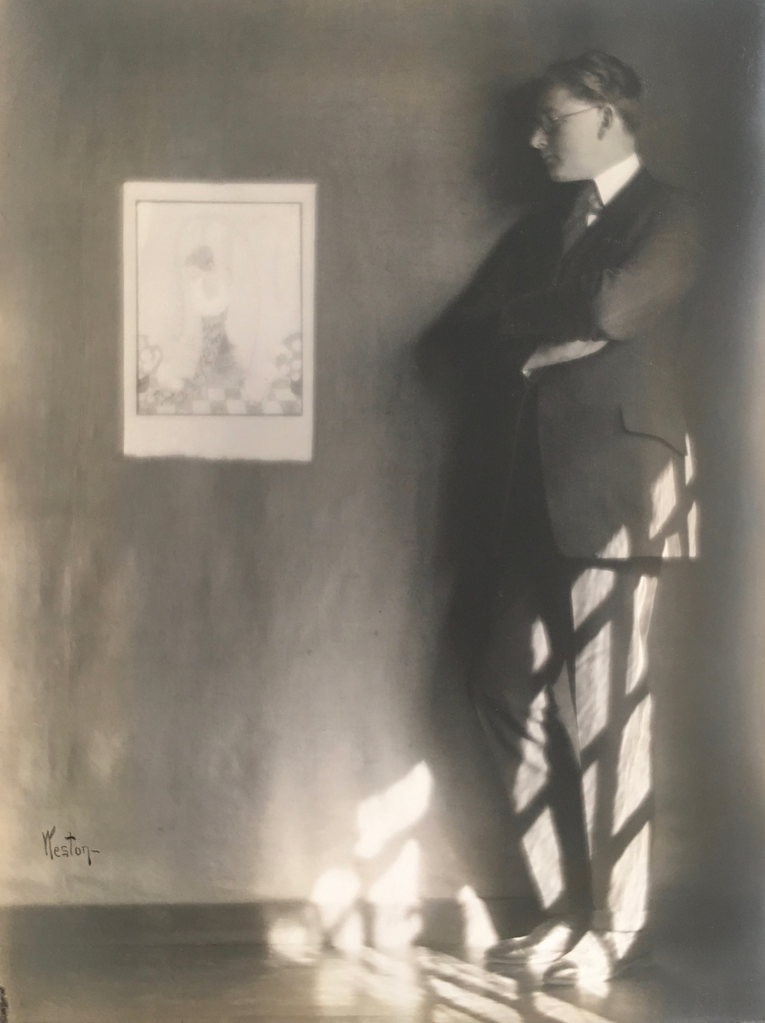

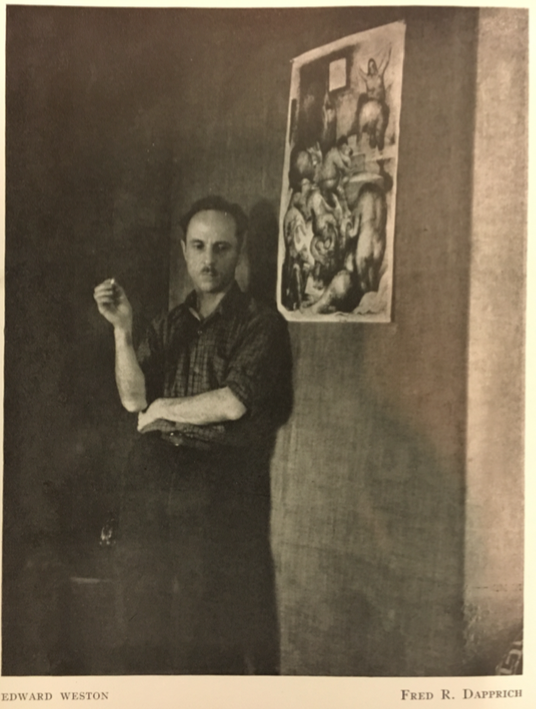

Use of the same signature appears in a 1915 portrait of Hollywood set, costume and production designer, George Hopkins (Not in Conger).[8] Hopkins’ portrait differs substantively from the typical work Weston produced for his casual studio clientele. Here, through sophisticated composition, light and tonality, Weston expresses his and Hopkins’ mutual artistic sensibilities. As with Gaunt Driven Boughs, the signature is purposely integrated into the aesthetic balance of the image.

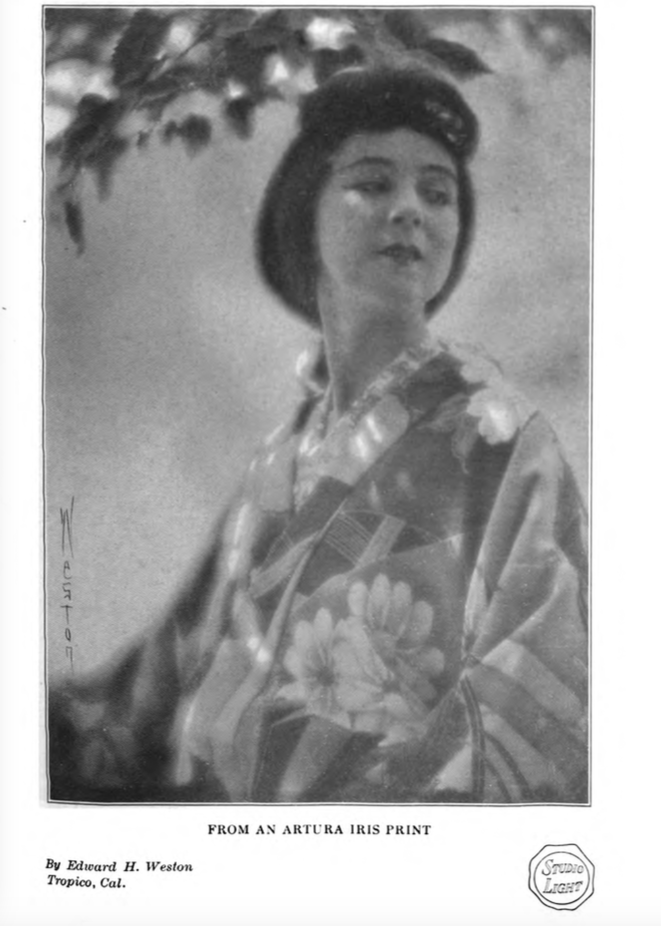

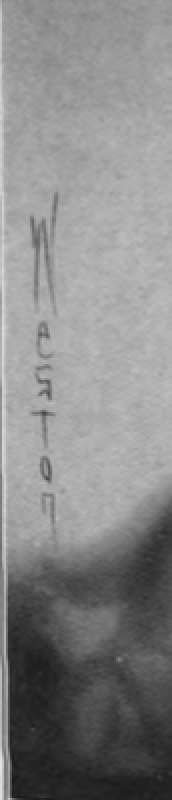

A dramatic example of Weston adapting his signature to suit the aesthetic of a photograph is the appropriately Japanesque vertical format employed on A Fleck of Sunshine (Not in Conger), his 1916 portrait of dancer Ruth St. Denis costumed in a kimono. Once again, Weston’s signature on the print serves as an integral compositional component.

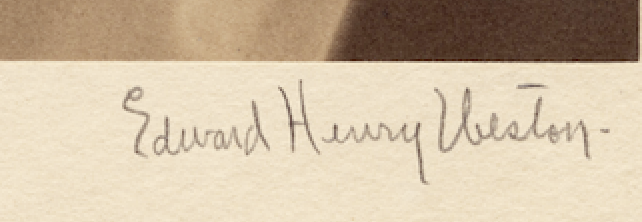

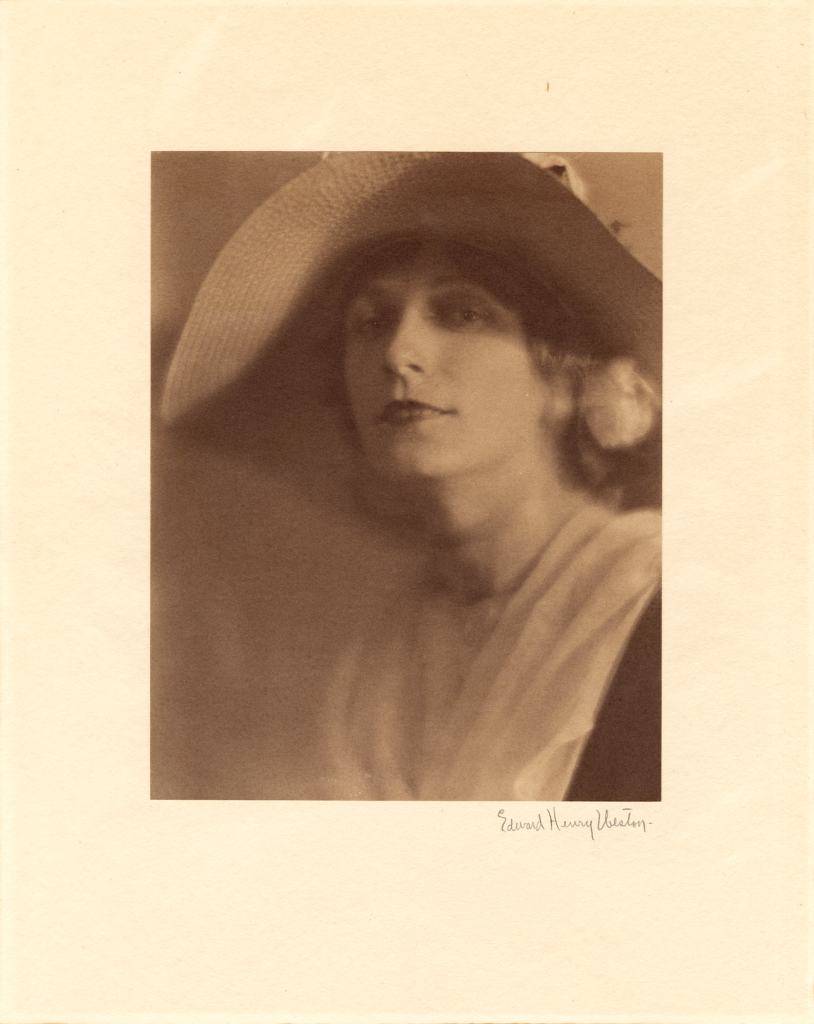

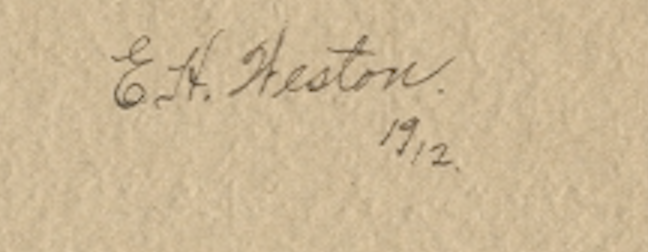

Although the portraits of Hopkins and St. Denis are signed simply “Weston,” he continued to utilize his full name through at least 1918, as evidenced by this portrait of soprano Gladys Gibbs Sherman (Not in Conger).[9] Unlike those of Hopkins and St. Denis, the portrait of Sherman is signed on the mount, recto, below the image, not on the print itself. Importantly, the cursive script applied in “Edward” and “Weston” differs from that used previously. No longer a compositional device or an aesthetic affectation, this signature is just that: Weston’s actual signature and, except for the inclusion of the middle name, heralds a style aligned with his modern work of the 1920s and beyond.

The 1920s

“More and more I realize I must conserve my strength for the work I love.”[10]

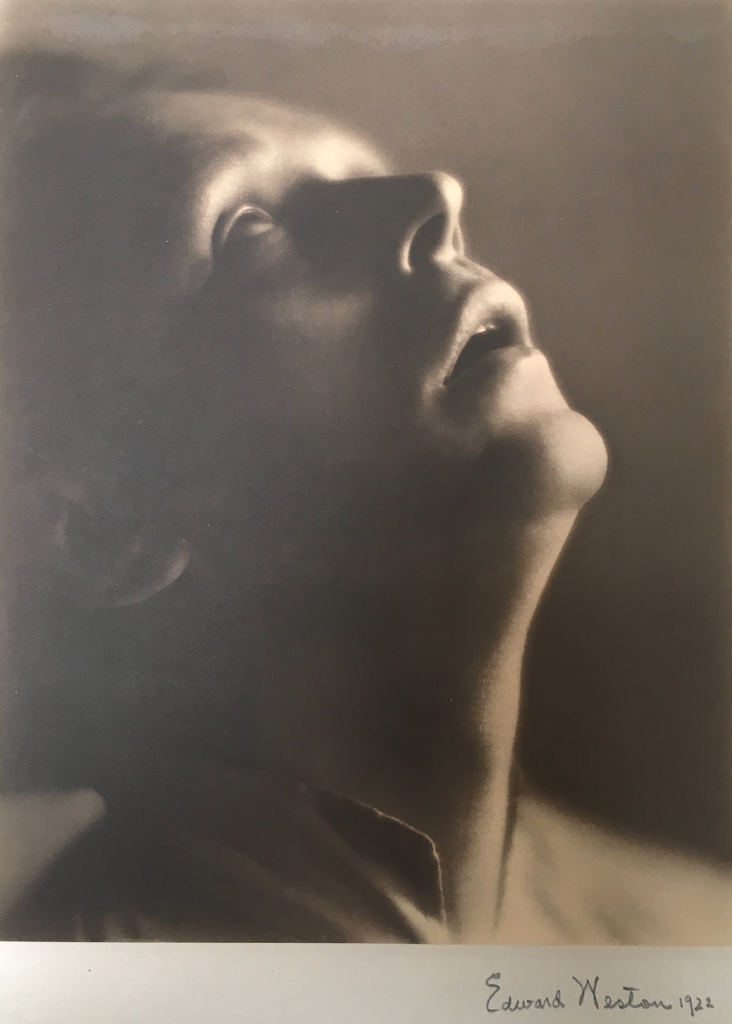

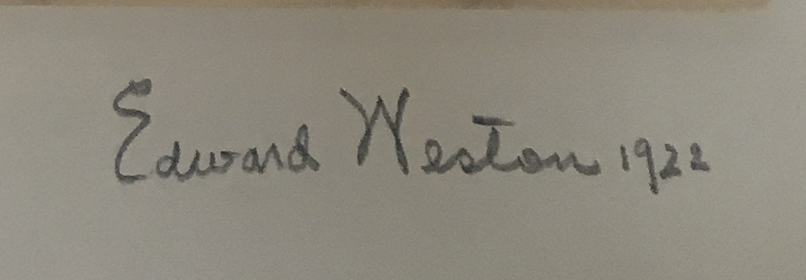

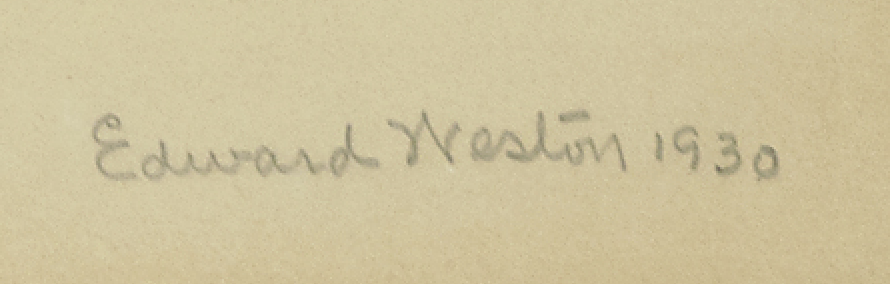

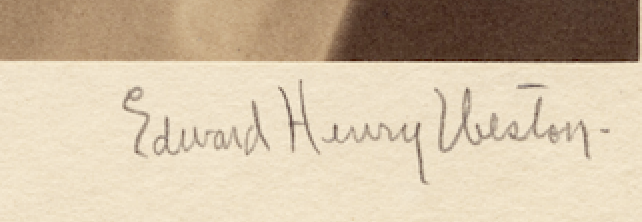

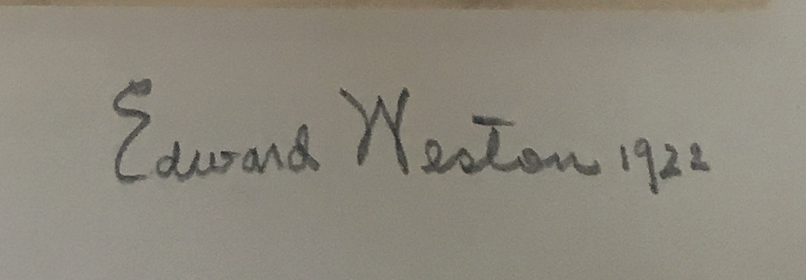

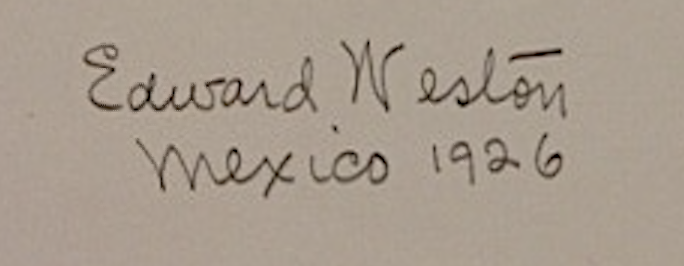

Weston’s mature cursive signature emerges fully in the early 1920s. An example is this dramatic 1922 portrait of composer and musician Henry Cowell (Not in Conger), signed and dated on the mount, recto, below the print: “Edward Weston 1922.” Noteworthy is the elimination of Weston’s middle name or initial. He is now “Edward Weston,” not Edward Henry or E.H. Weston. Gone, too, is any trace of Pictorialist penmanship. In fact, the shapes of the “E” and “W” seen here are identical to those found in Weston’s signature up through the 1940s. Weston has finally settled on a straightforward signature fit for a modern photograph.

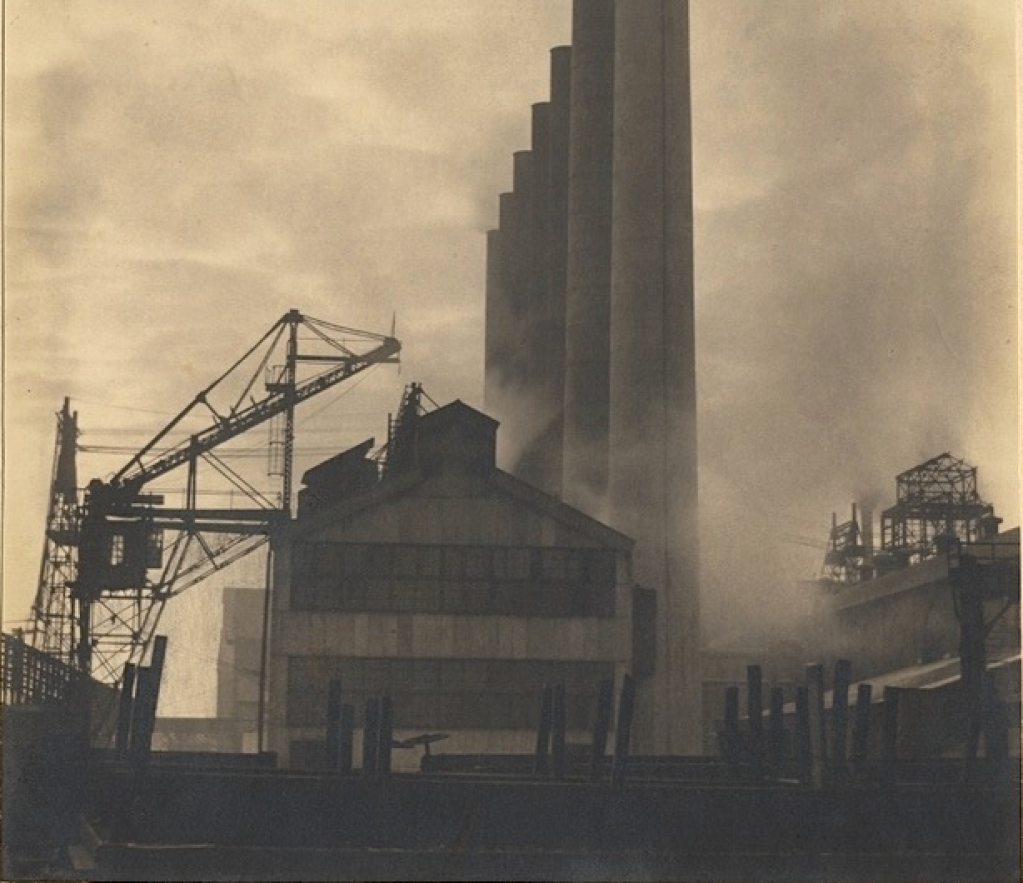

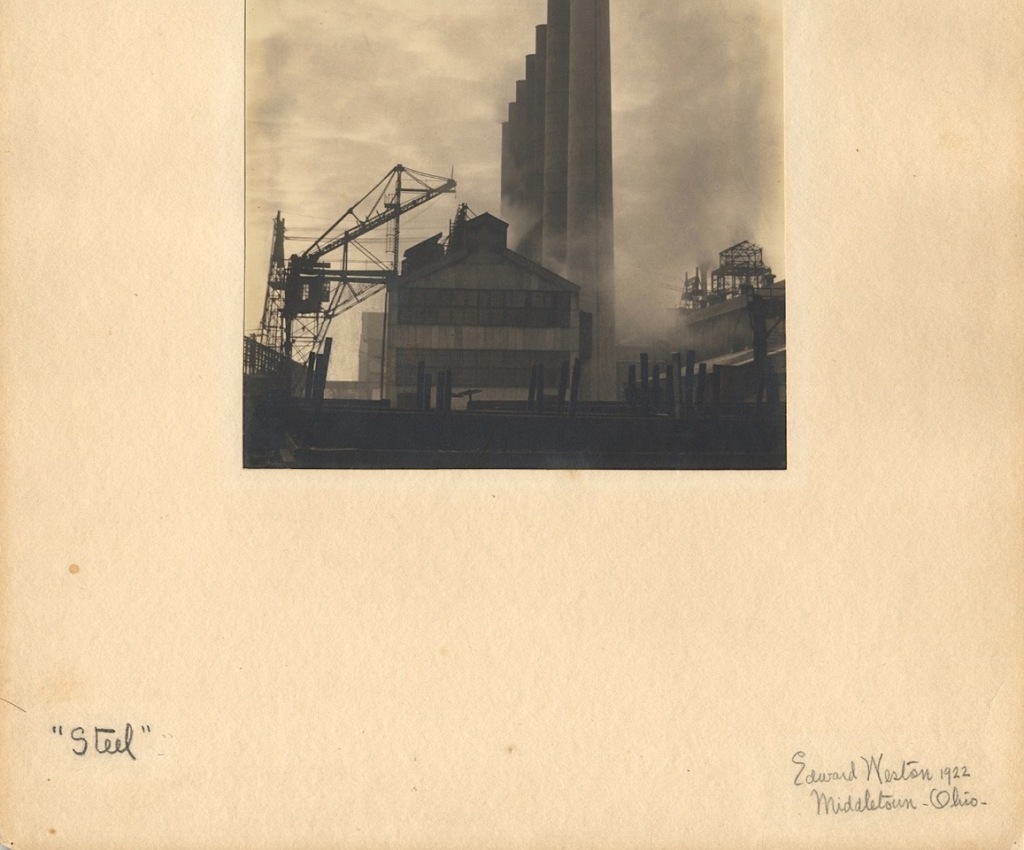

The same signature appears on this striking 1922 depiction of the ARMCO Steel Mill, taken during Weston’s trip to Middletown, Ohio to visit his sister May Seaman and his subsequent journey to New York City to meet Alfred Stieglitz. Yet, here we encounter a variation: the inclusion on the mount below the print of a title, “Steel,” and the appending of a location to Weston’s name and date, “Edward Weston 1922 / Middletown -Ohio-.”

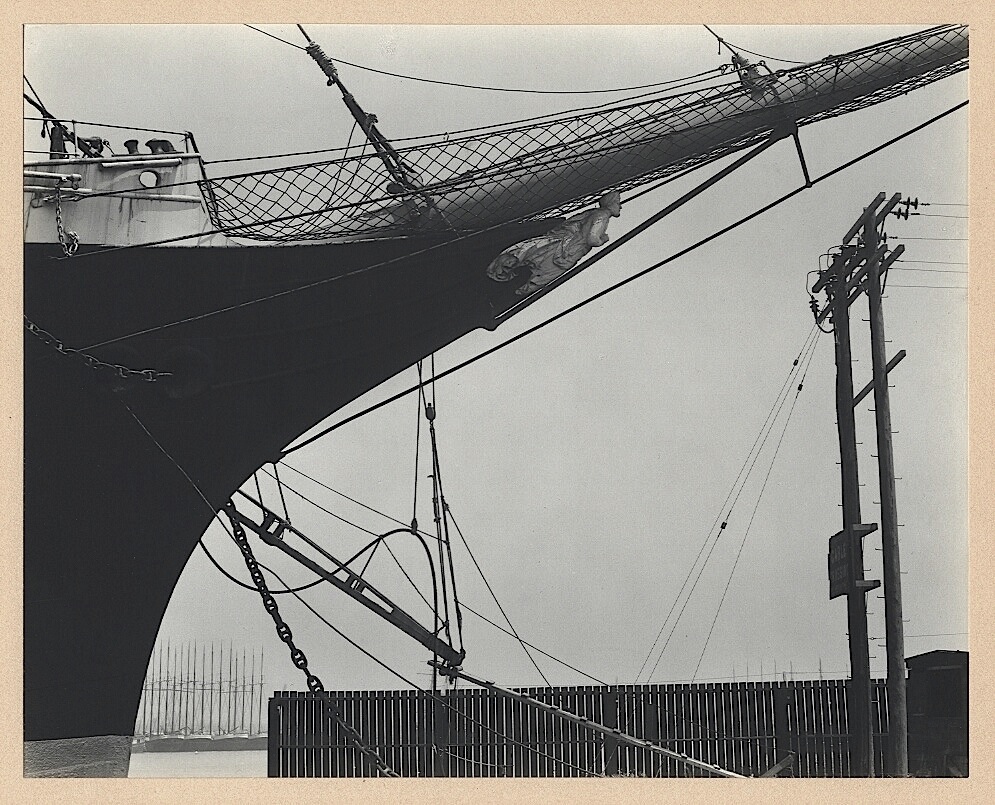

Weston also employs this approach in a 1925 print of Boats, San Francisco (Conger 158/1925), where the signature “Edward Weston / San Francisco 1925” appears at the lower right of the mount, recto. Generally speaking, Weston titled his photographs from this time forward.

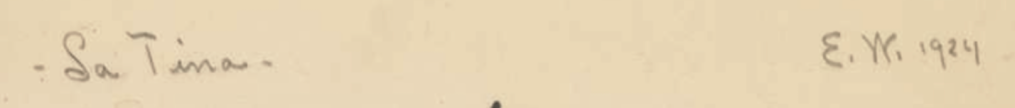

An unusual variation in the 1920s is Weston’s use of initials to sign and date a work, as seen on the mount, recto, of La Tina, a moving portrait of Tina Modotti, taken in Mexico in 1924.

The 1930s

“I decided to put a sign in my showcase, a manifesto to the public similar to the one on my wall,—“no retouching… Also mentioning the work will be finished according to my wishes, and unretouched or I will not sign my name. …”[11]

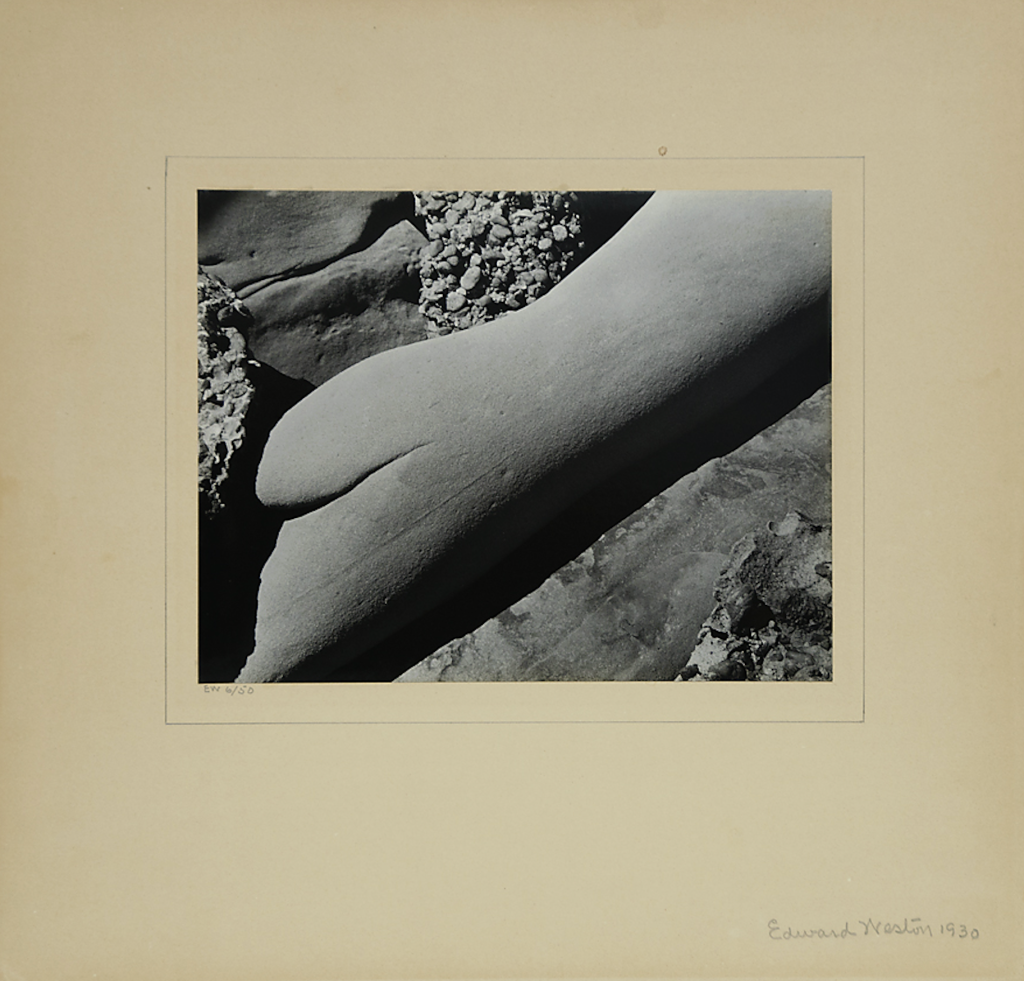

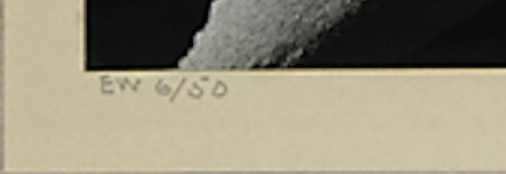

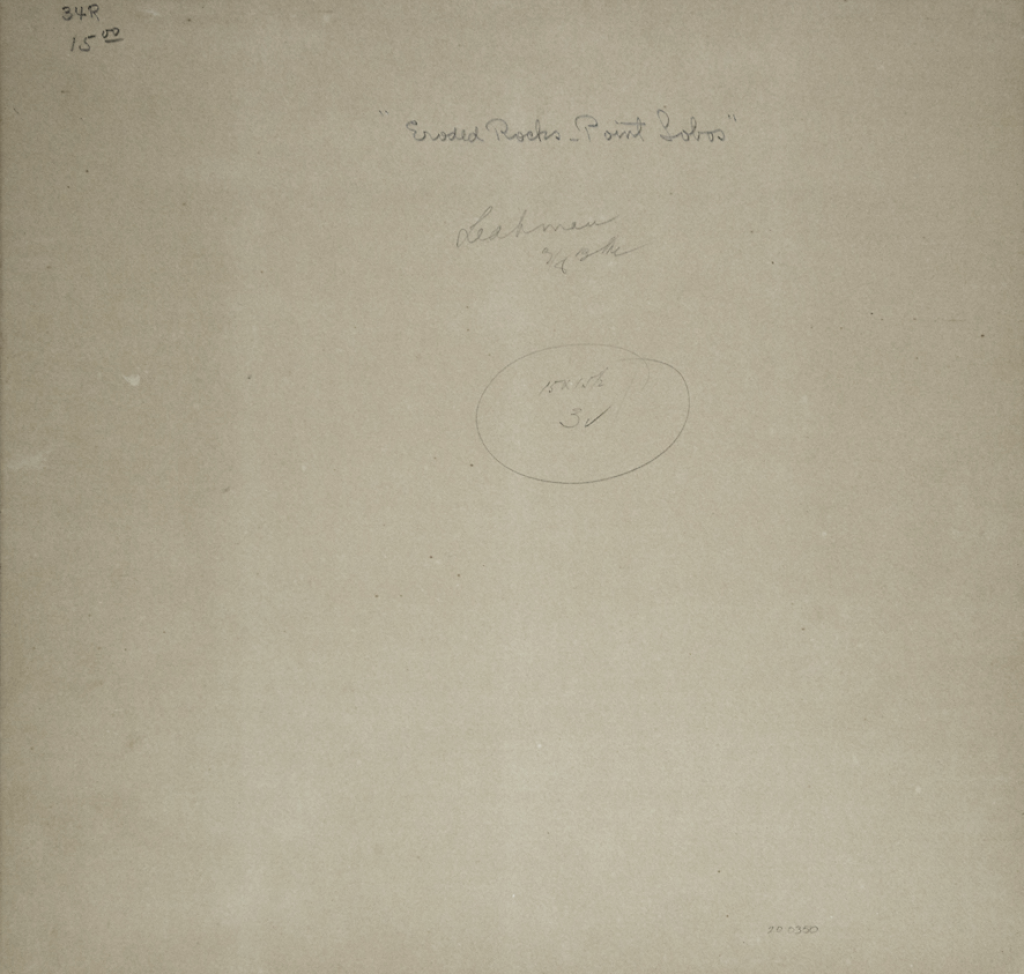

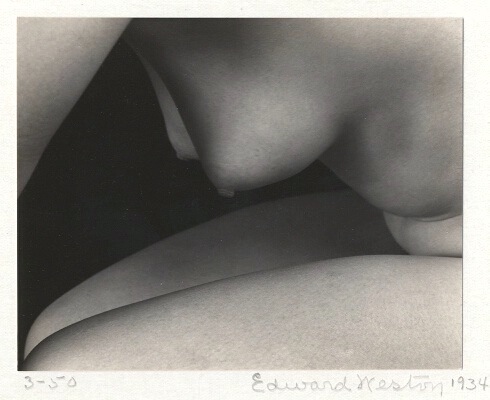

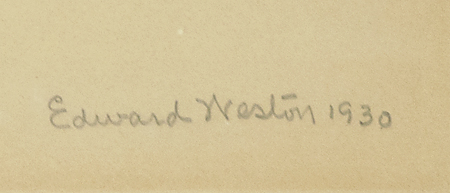

In 1930, Weston began issuing prints in projected editions of fifty, although no edition was ever fully realized. On the mount, recto, he numbered each print “1/50,” “2/50,” etc. and added the negative date after his signature. An additional signature, title and date, as well as a negative number, and more rarely a price, appear on the mount, verso. Two examples are this torso-like 1930 Eroded Rocks, Point Lobos (Not in Conger), numbered 6 of 50 and the beautiful 1934 nude, Gretchen (Conger 814/1934), numbered 3 of 50. Eroded Rocks is also inscribed at upper center, verso: “Eroded Rocks, Point Lobos” and upper right, verso: “34R / 15.00.”

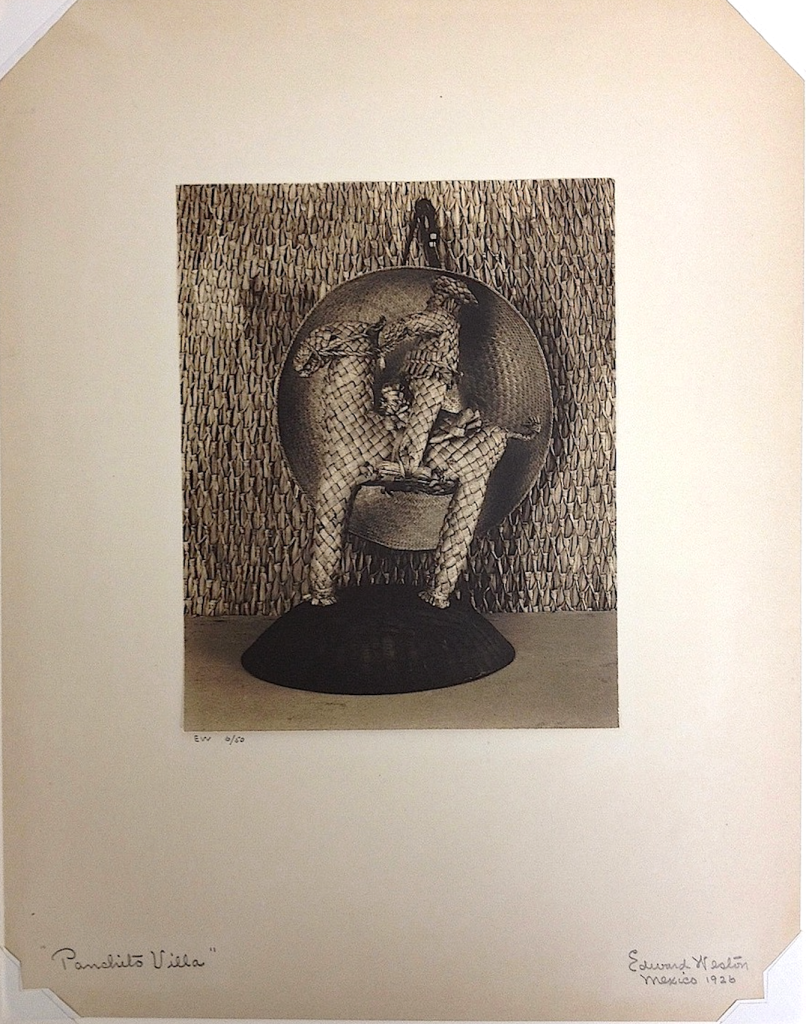

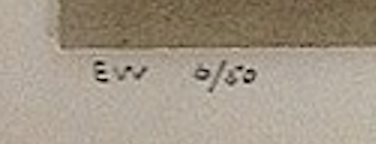

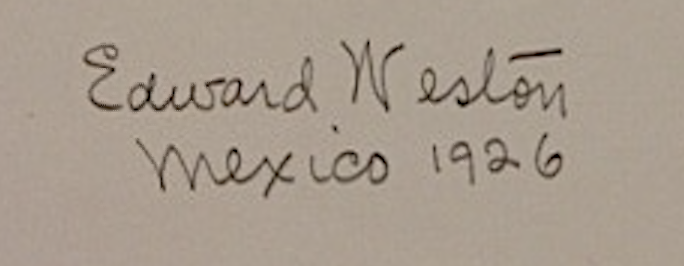

From 1930 on, Weston occasionally went back to prints he had made earlier and added an edition number. An example, below, is “Panchito Villa” (Conger 197/1926), a palladium print made in Mexico in 1926 to which Weston added his initials and the edition number “EW 6/50” on the mount, recto, sometime after 1930.

1930 also marks the beginning of Weston’s use of glossy paper, which he came to prefer to the matte surface paper previously in vogue. As he wrote in his Daybook on 15 March 1930: “… But I have already made a showing, and hope my next exhibit will be on glossy paper. What a storm it will arouse!—from the “Salon Pictorialists.” It is but a logical step, this printing on glossy paper, in my desire for photographic beauty. Such prints retain most of the original negative quality. Subterfuge becomes impossible, every defect is exposed, all weakness equally with strength. I want the stark beauty that a lens can so exactly render, presented without interference of ‘artistic effect.’”[12]

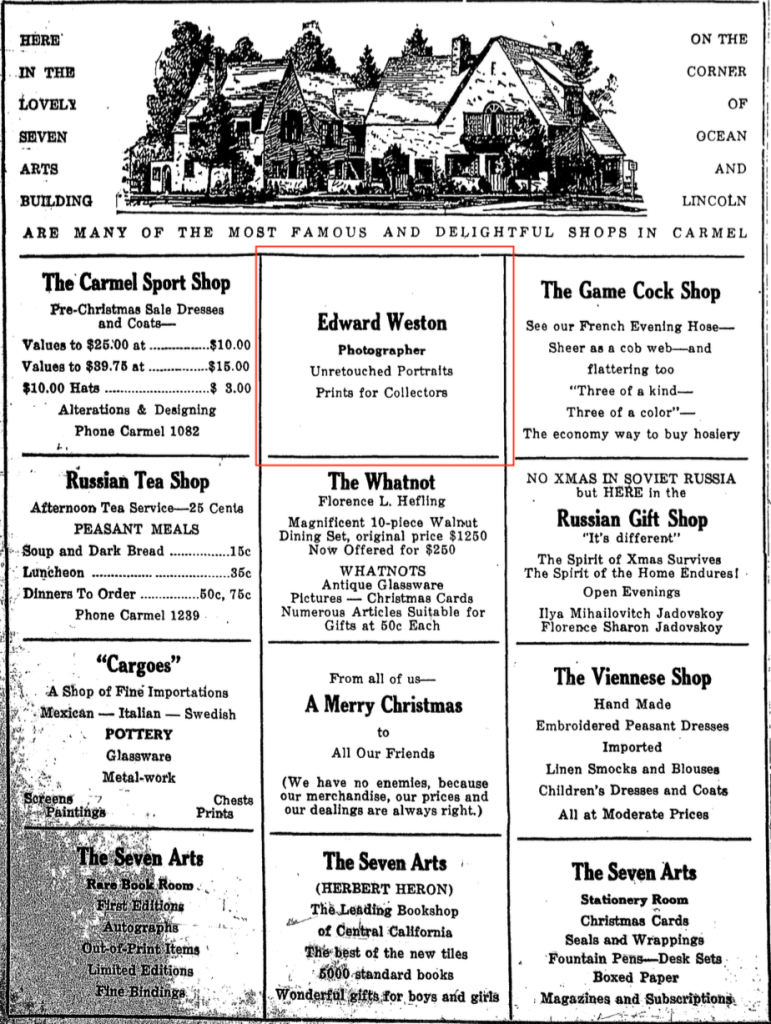

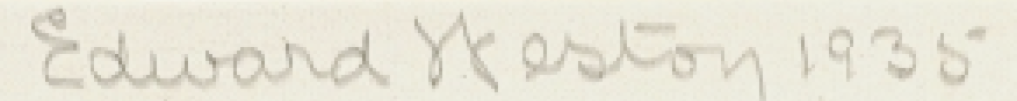

Another significant venture emerges in 1935 with the introduction of the subscription driven Edward Weston Print of the Month Club. Here, a select print was issued in a projected edition of forty, with the number corresponding to the order in which a collector subscribed. As with the earlier edition enterprise, EWPOMC prints bear an edition number as well as a signature and date on the mount, recto. This print of the arrestingly abstract 1935 Elbow (Not in Conger) is a fine example. It is numbered, signed and dated below the print: “12-40” and “Edward Weston 1935” as well as inscribed verso: “EW POMC-June / —Elbow—.” In other words, Elbow was issued in June 1935 and this print was intended for subscriber number twelve.[13]

The 1930s are important for another reason as well, for it is at this time that Weston draws his signatory line in the sand regarding retouched portraits. As he wrote in his Daybook entry for 14 October 1931: “… I will do portraits only when I want to, of those I want to, the way I want to,—and charge well for the privilege. I will have my revenge for all the prettified, retouched females I have had to do, for all the portraits I have sent out which were not my work: portraits so nauseating that I have covered them over when signing my name. …”[14] He comments similarly in his 8 December 1932 Daybook entry: “… But I will not sign, except duplicate prints from old negatives, any retouched order. This still leaves another step, which will follow logically, that I will accept no order that I am ashamed to sign, that I will never retouch again. …”[15]

Weston formalized this stance, publicly and determinedly proclaiming “Unretouched Portraits” at his gallery, in advertisements and his own promotional brochures.

From this point on, Weston remains artistically uncompromising. Regardless of subject matter—portrait, landscape, nude, or still life—he will refrain from signing any photograph he deems unworthy of his name.

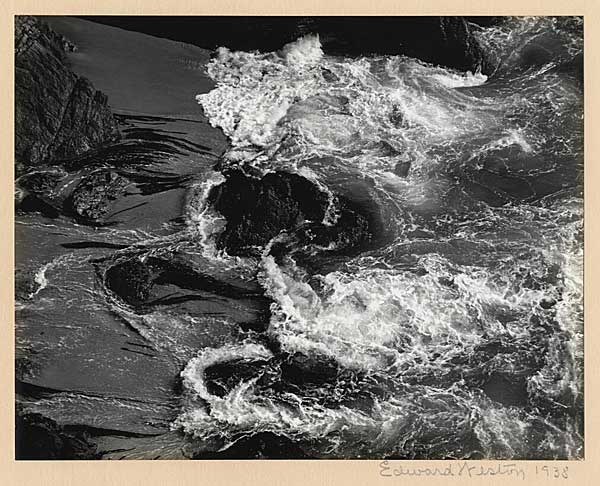

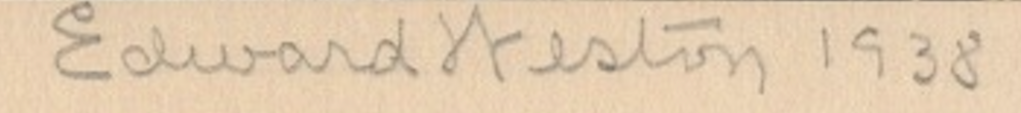

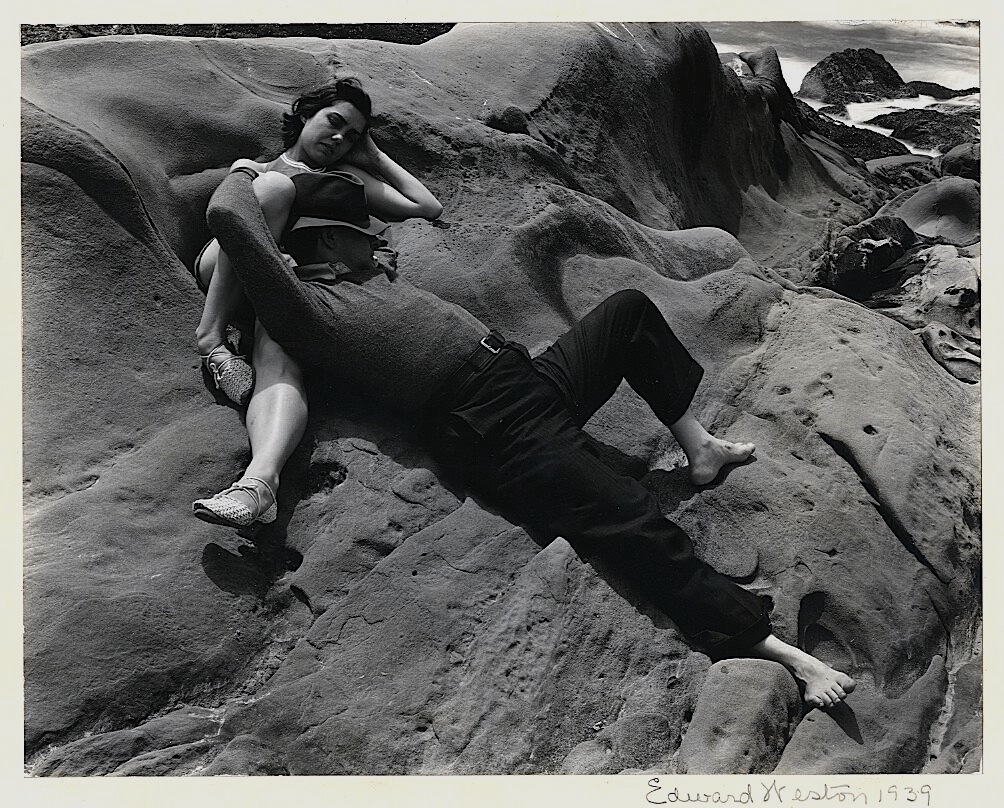

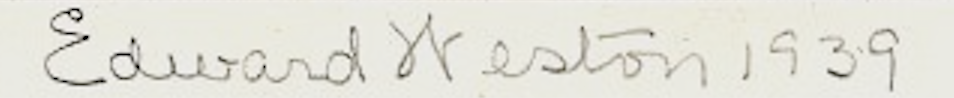

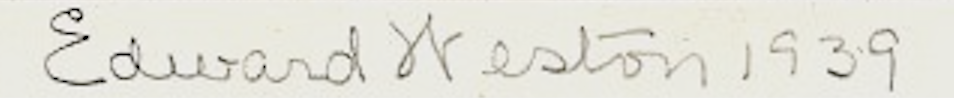

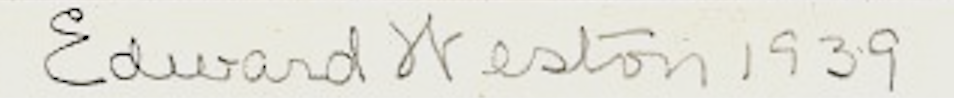

Very little changes in the style of Weston’s signatures from the 1920s on. Two examples from the late 1930s which reflect his use of a full name and date on the mount, recto, are the 1938 Surf, China Cove, Point Lobos (Conger 1367/1938) and this 1939 portrait of Zohmah and Jean Charlot reclining on the rocks at Point Lobos (Conger 1473/1939).

A remarkable attribute of this print of Zohmah and Jean Charlot is the bevy of labels adhered verso. All relate to the 1940 Photographic Society of America Invitation Salon and its subsequent venues.[16] Weston has also inscribed the print, verso: “No. 1—Jean and Zohmah Charlot” and “Edward Weston / R1, Box 162 / Carmel, Calif.”

The 1940s–1950s

“I will be more widely acclaimed and my work sought for after I am gone. I must realize that every print I send out (God forgive the portraits) with my signature is going to be severely criticized by those who know—.”[17]

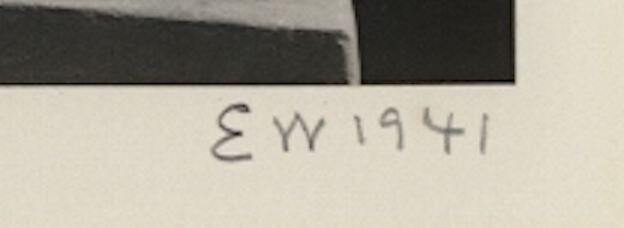

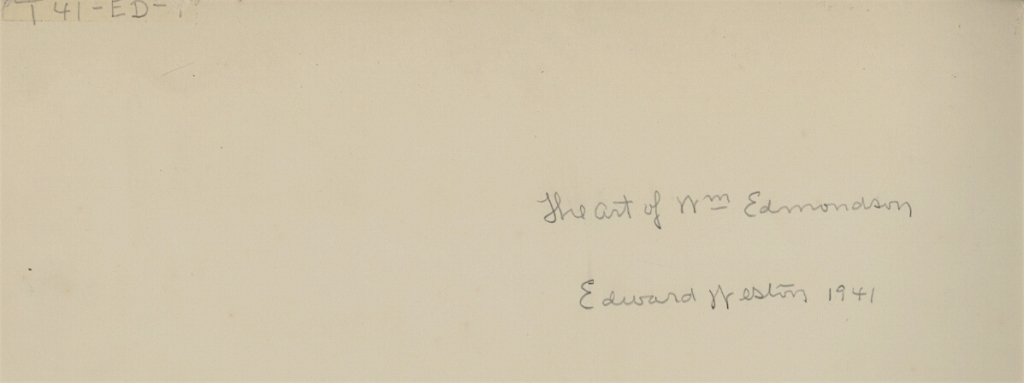

Weston introduced a stylistic change in the early 1940s, replacing his full signature, plus negative date, with only his initials, plus negative date. He sometimes included a full signature, title and date on the mount, verso, but this practice waned as the decade progressed.

In this vintage print of William Edmondson’s Sculpture (Conger 1633/1941), we find him employing both: initials and date “EW 1941” on the mount, recto, lower right directly below the print and the inscription, verso: “The Art of Wm. Edmondson / Edward Weston 1941.”

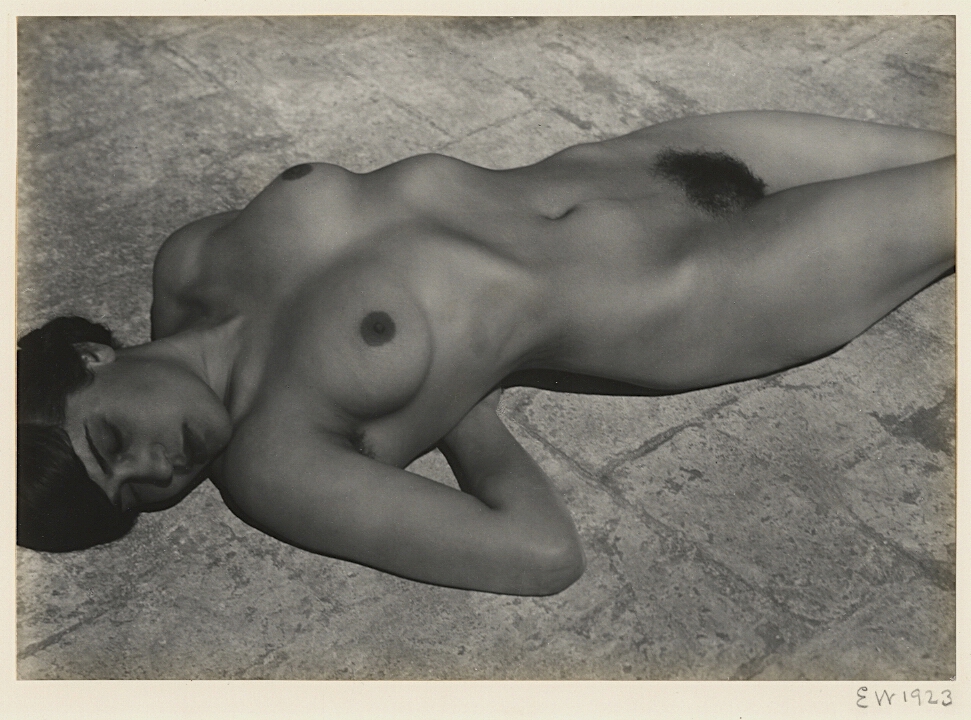

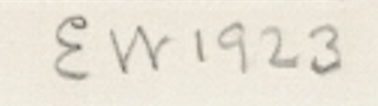

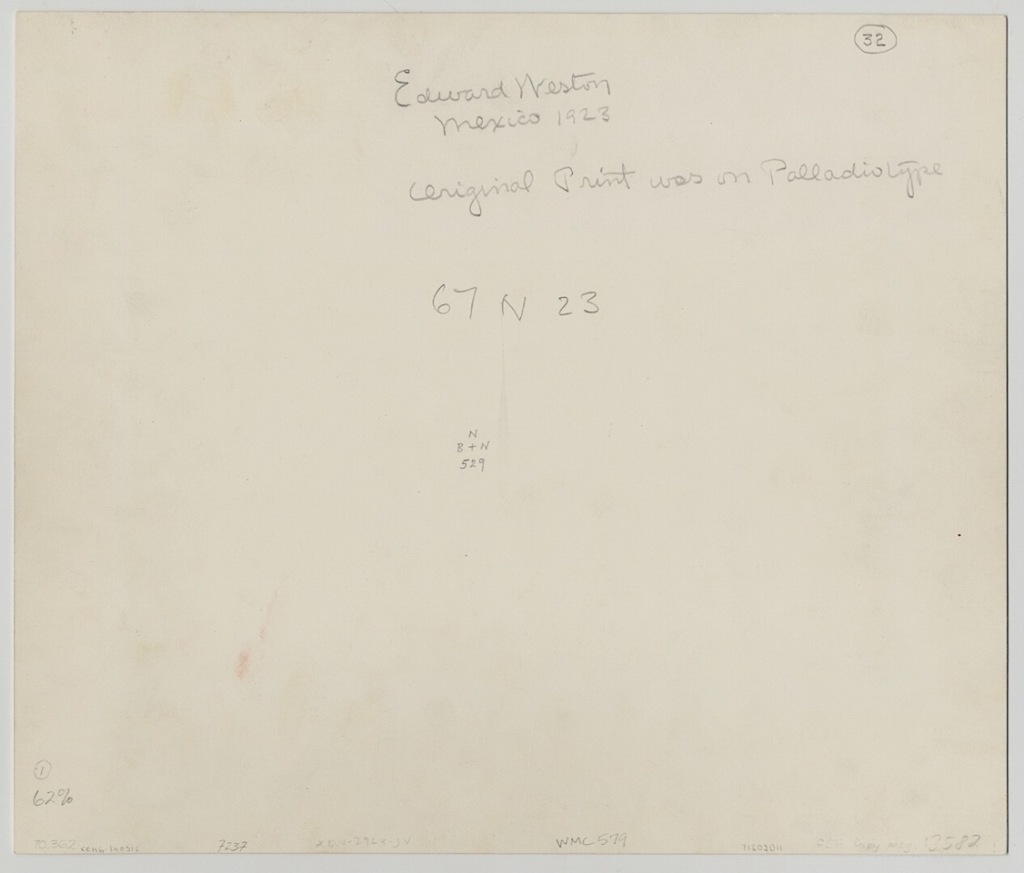

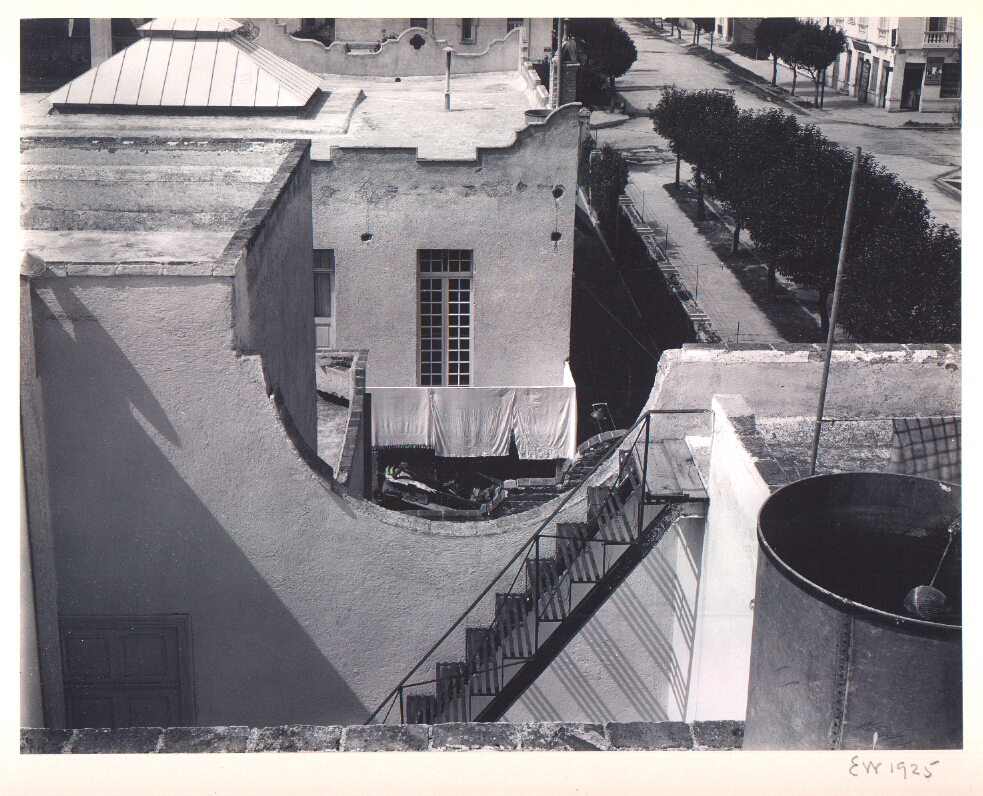

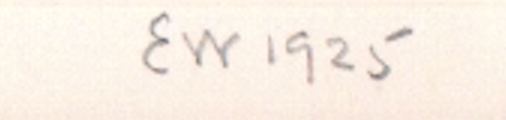

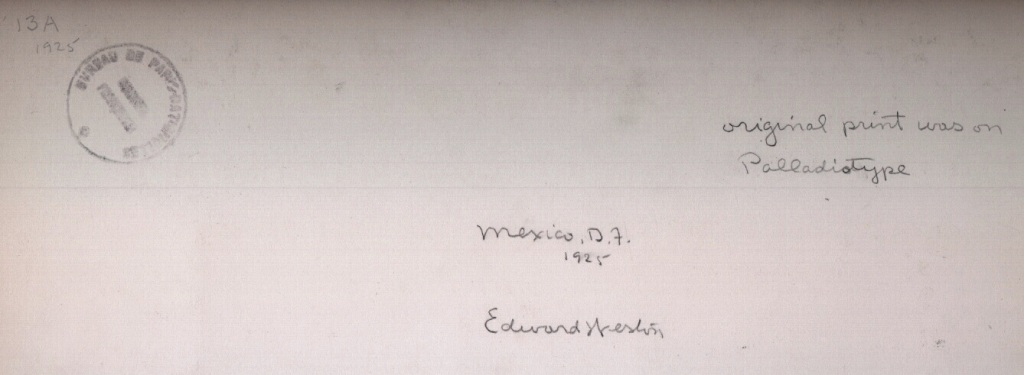

Weston reprinted earlier negatives in the mid-1940s as well, signing them with initials and the original negative date on the mount at lower right, recto, as well as inscribing his full name and information such as location, title, print data and negative number, verso. Two examples of mid-1940s prints made from negatives taken during his 1923–1926 sojourn in Mexico are this stunning nude of Tina Modotti, Nude on the Azotea, (Conger 111/1923) and the architectural Desde la Azotea (Conger 136/1924).

The “BUREAU DE PARIS BATIGNOLLES” stamp verso of Desde la Azotea indicates it was likely printed in 1949 for Weston’s two 1950 Paris exhibitions.[18] Another indication of a 1949 printing is the deterioration evident in Weston’s handwriting (see concluding discussion, below). Note, too, that Weston dates Desde la Azotea 1925, while Conger dates it 1924. Evidently Weston’s memory for work done more than twenty years in the past was as fallible as ours likely would be.

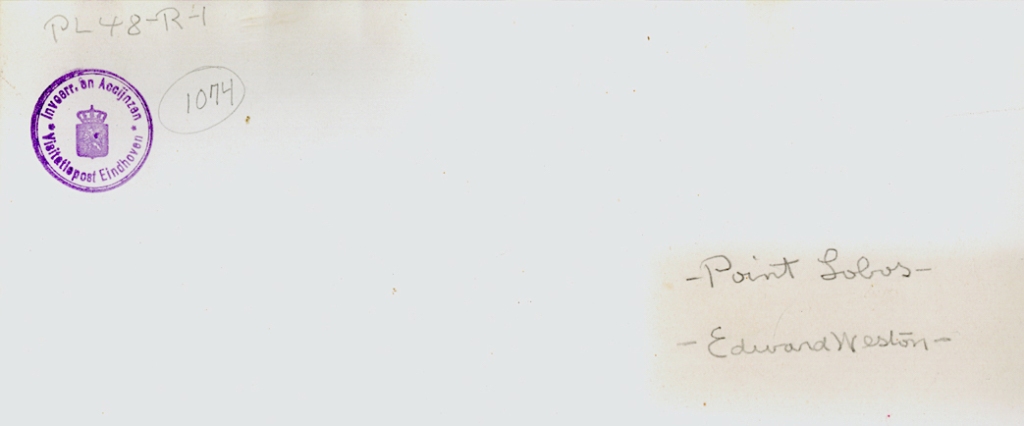

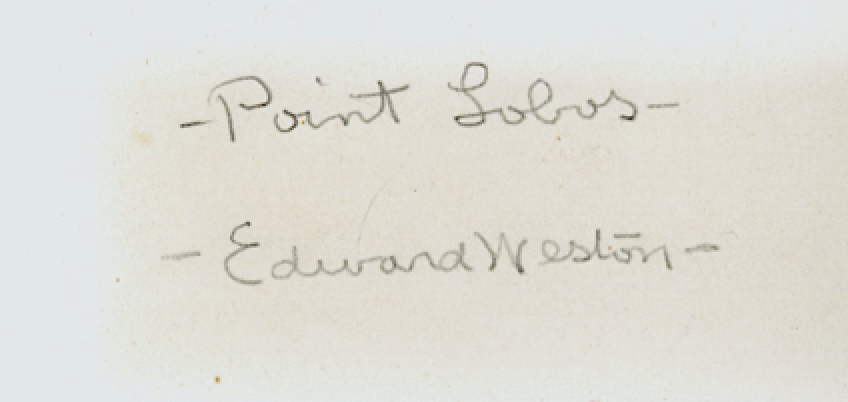

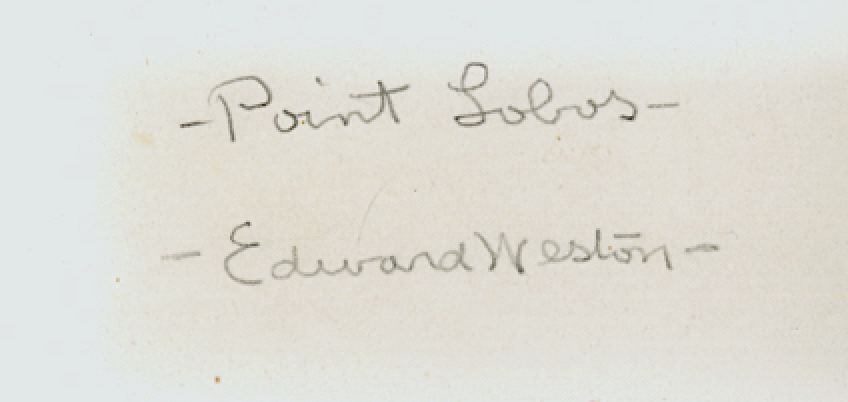

Weston ceased photographing in 1948 due to the progression of his Parkinsons disease. His final photograph, the 1948 Eroded Rocks, South Shore, Point Lobos (Conger 1826/1948) is signed using initials/date recto: “EW 1948” and title/full name verso: “—Point Lobos— / —Edward Weston—.” He also inscribed the negative number, “PL48-R-1” at the upper left, verso. Of added interest is the stamped Eindhoven exhibition label, at the upper left, verso.[19].

Although no longer photographing, Weston remained professionally engaged with exhibitions, the Willard Van Dyke film The Photographer, and selecting and signing prints made from existing negatives for two separate projects in the early 1950s. Both were printed under Weston’s supervision by his son, Brett.

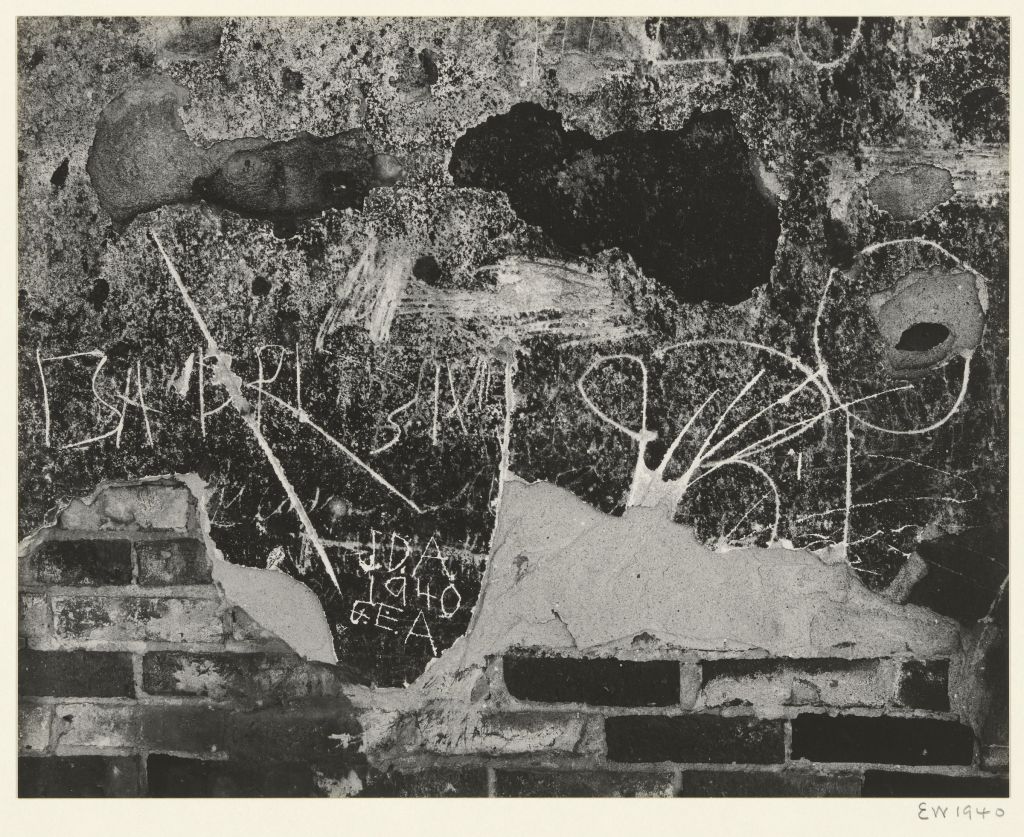

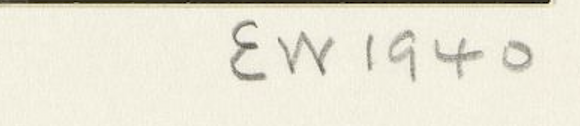

The first of these projects is the Edward Weston Fiftieth Anniversary Portfolio 1902–1952, which was ready for release in late 1951.[20] Limited to an edition of one hundred copies, the Portfolio is comprised of twelve prints, each signed recto with his initials and negative date at lower right immediately below the print. An example is this Portfolio print of Wall Scrawls, Hornitos (Conger 1504/1940).

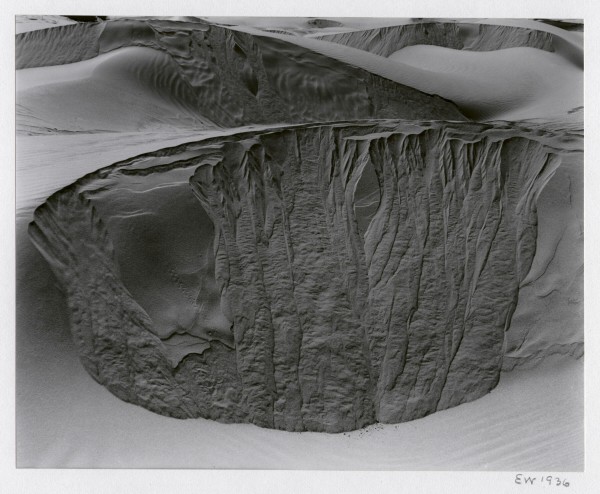

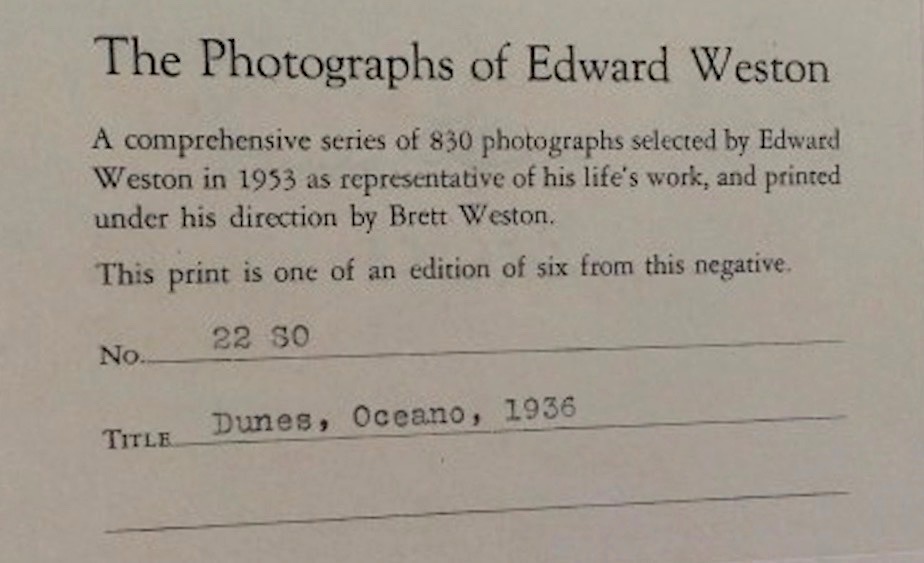

The second enterprise, the Project Prints, proved far more ambitious: 830 photographs, each in an edition of six (later increased to eight), selected by Weston and ultimately printed under his supervision by Brett between 1952–1955.[21] As with the Portfolio prints, Weston signed each with his initials and the negative date on the mount recto, below the print at the lower right. Each Project Print bears the label on the mount, verso as pictured below.

An example is this print of Dunes, Oceano, a 1936 negative printed by Brett Weston about 1953.

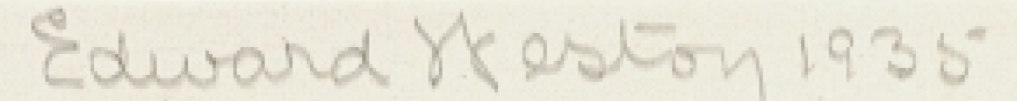

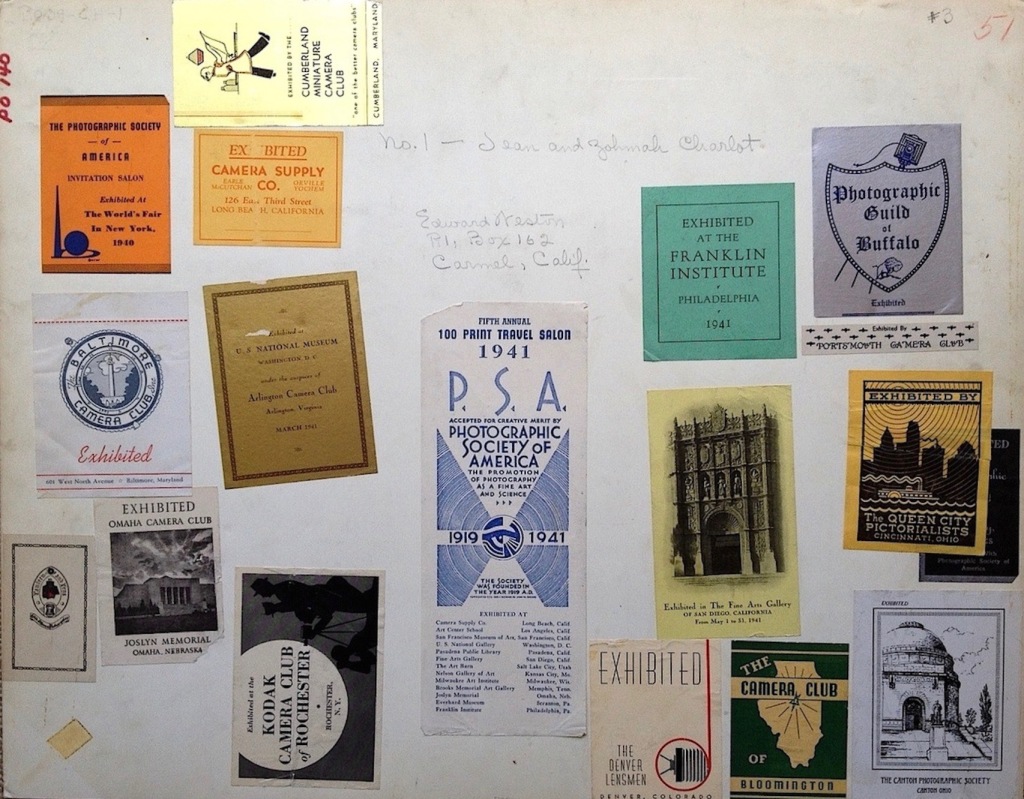

No study of Weston’s signatures would be complete without a discussion of his handwriting from the mid-1940s through the early 1950s, when the physical deterioration wrought by Parkinsons disease becomes increasingly evident. The fluidity and control characteristic of earlier signatures gives way to rigidity and instability as Weston finds it more and more difficult to handle a writing implement. Overall, titles and inscriptions become labored and unsteady, writing tends to slope. Most apparent are the alterations in the “E” of Edward and the “W” of Weston. The former graceful curl atop the “E,” present since the late 19-teens, and the vibrant “W” with a looped lower left both disappear by the late 1940s.

Signature on Zohmah and Jean Charlot, 1939

Later, compromised inscription, verso of Eroded Rocks, South Shore, Point Lobos, 1948

One can only imagine the determined struggle involved in initialing all those Project Prints, where the labored and diminished “EW” is particularly apparent. Here, the “E” is comprised of two joined curves without any loop or flourish, the “W” appears more like two joined “v”s, and there is a slope to the overall signature.

Project Print signature on Dunes, Oceano, 1936, printed about 1953 by Brett Weston

By 1950, it required extreme effort for Weston to write, a difficulty he expressed in the following letters to friend and fellow photographer, Donald Prendergast:

27 April 1950: “Dean Don – / I don’t write much anymore, too difficult, but for such a letter from you, I would answer with my teeth or toes! It was better I assure you than all the palliatives I have tried and give up as nothing more. / For all you said and for all it did to me – mil gracias amigo. / I was glad to get news of your activities. Your life seems to be a “great reservoir of confidence from which everyone can drink.” Does this leave you any time or strength to paint? / Excepting for color [surprised] I have done no photography for a couple of years. I have been busy however with shows [one-man] in London & Paris; both of them wound up at the American Embassies, by invitation. At least 13,000 saw the Paris show, it went over big! / There is a documentary film now released by the State Dept. [USIS] called “The Photographer.” It is about me, I “play” the lead, and done by Willard Van Dyke. I recommend even though I have my fact & form in it; you will see many familiar scenes, even the cats! / I must end this long letter. / Remember me to Emma Albans. / Love to you – / “Eddie” / 4-27-’50.”[22]

and

17 November 1950: Dear Don – / I can get so far in a letter and find it readable, but about here — unless I concentrate — my writing gets pretty rough, or school-boyish, and takes all the joy out of said writing. / Your series of letters — which I treasure and will keep for posterity — has kept me gay for days. The plan proposed for the football field is worthy of Thurber — and that’s a lot from me. / Now if I get interrupted for 15 min., I should be able to start all over again with a firm grip & no gripe. An idea! I’ll train the cats to stage a fight or a bout of love-making every so often. / Did you see “My Camera on Pt. Lobos”? by one E.W.? / I call this a long letter / Maybe a better one soon—. Love and! Eddy.”[23]

Weston may have been overcome by infirmity in the 1950s, but his legacy remained undiminished and has only increased over time. As Jacob Deschin wrote in an obituary in the 5 January 1958 issue of The New York Times:[24]

When Edward Weston, generally acknowledged as America’s greatest photographer, died at his home in Carmel, Calif., last week, photography lost its best representative among the arts, for Weston was esteemed by artists in other fields as a kindred spirit. Perhaps his most valuable legacy to photographers was his integrity as a photographer and his uncompromising attitude toward the medium as a vehicle of personal expression. / Truly dedicated, Mr. Weston believed in perfection of technique as a language that had to be mastered thoroughly before one could say anything worth while in photographs. He was as zealous a critic of his own work as of that of others, always insisting on nothing less than the best. / As a teacher, he inspired the students who visited his studio on Wildcat Hill as if it were a shrine. When they left him at the completion of a course, they took with them more than a better understanding of techniques. A wholly new concept of photography had been opened to them and they were prepared to use the camera as a creative tool rather than as a mere recorder. / When the writer visited Mr. Weston at his home a few years ago, he was impressed by his unbounded enthusiasm, undiminished by illness, and the pride, almost boyish, in which he showed his pictures, and discussed photography generally. He smiled at his early efforts, in which he had followed the fashions of the times—pictorialism and stiff studio portraits—and displayed lovingly his later work, the work which truly reflects his approach and has now become a significant part of photographic history. / Weston remains a symbol of the highest ideals in photography. Few photographers worked so consistently over a lifetime to build and maintain a personal standard of such top-level artistic achievement, and held to it in spite of the allurements of the commercial world. Perhaps the greatest compliment ever paid him was the remark of a middle-aged woman visitor to one of his New York exhibitions. When asked why she liked a certain picture she replied simply, ‘Because it makes me feel so good.’

A Signature Sampler, 1912–1953

1912

1918

1922

1924

1926

1930

1935

1939

1941

1948

PROJECT PRINTS, 1953/1954

NOTES

[1] Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, vol. 1, Mexico, ed. Nancy Newhall (Millerton, N.Y., 1973), 30 August 1926, p. 189.

[2] Ibid., vol. 2, California, 18 March 1930, p. 148.

Weston quotes this letter, written to his father on 20 August 1902, in his Daybook entry for 18 March 1930.

[3] Weston’s photographs were critiqued and/or illustrated (and his name reported as either E.H. Weston or Edward Henry Weston) by the following publications in 1906: Camera and Dark-Room, April 1906 and American Amateur Photographer, June 1906.

[4] Op.Cit. The Daybooks of Edward Weston, Introduction p. xviii.

[5] [Advertisement] Edward Weston, “Bungalow Photograph Studio Edward H. Weston… I wish to announce the opening about July 1…” The Glendale News, 17 June 1910, n.p. [6.]

This, Weston’s first advertisement for his soon to open—and first—Tropico Studio, reads: “BUNGALOW PHOTOGRAPH STUDIO / EDWARD H. WESTON / To patrons and friends I wish to announce the opening about July 1st of my new studio, now being erected on Brand Boulevard just north of Tropico Avenue. / Artistic Portraits Commercial Dept. / Children a Specialty / Phones, Sunset 111; Res. Sunset 257.”

A subsequent advertisement in The Glendale News on 15 July 1910 announced the actual opening: “Bungalow Studio / NOW OPEN / Brand Boulevard, north of Tropico Avenue / I have a display of my work at Chandler & Lawson, Glendale / WESTON, Photographer.”

[6] Weston photographed the Oliver family a number of times over the years. The earliest known example is this portrait of Lois at the age of three in 1910. Others which have been identified depict Lois again singly and Lois with her brother Roland, age three, in 1912; of the infant Hubert and another of Roland in 1913; and finally, portraits of Lois, Roland and Hubert in 1914. (All photographs Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

[7] Gaunt Driven Boughs in the Sweep of Open Wold aka Valley of the Long Winds aka The Wind Storm aka Valley of the Lone Wind was exhibited and variantly titled in the following exhibitions:

(1) John Wanamaker Department Store, Eighth Annual Exhibition of Photographs, Philadelphia, PA, 1–31 March 1913. Titled therein: “Gaunt Driven Boughs in the Sweep of Open Wold.”

(2) The Shakespeare Club, Photography by Edward Henry Weston, Pasadena, CA, March 1915. Titled therein: “‘Valley of the Long Wind”

(3) Los Angeles State Normal School, [Solo exhibition] Los Angeles, CA, October-November 1915. Titled therein, according to a review in the Los Angeles Times: “Valley of the Long Wind.”

(4) Museum of Modern Art, Edward Weston: Photographs, New York, NY, 12 February-31 March 1946 [and subsequent traveling venues]. Titled and dated therein as: “Valley of the Long Wind,” 1913.

[8] George Hopkins (1896–1985) enjoyed a long and illustrious career that stretched from 1917 to 1975 and garnered him four Oscars. His work as a set decorator encompassed such acclaimed films as the silent classics Cleopatra (1917) and Salome (1918), both starring Theda Bara and for which Hopkins also designed the costumes; A Streetcar Named Desire (1951); Dial M for Murder (1954); A Star is Born (1954); Days of Wine and Roses (1962); My Fair Lady (1964); Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966); and his final film, The Day of the Locust (1975). It is possible that the drawing on the wall next to Hopkins in Weston’s portrait was done by Hopkins himself.

[9] This is one of three known portraits Weston made of Gladys Gibbs Sherman. (All three, Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

[10] Op.Cit. Daybooks, Mexico Aug. 26, 1924, p.91.

[11] Ibid., California, 13 June 1930, p. 167.

[12] Ibid., California, 15 March 1930, p. 147.

[13] The Edward Weston Print of the Month Club ran from 1935 to 1936 and was projected as an edition for thirty-five subscribers, with an additional five prints of each photograph reserved by Weston for exhibitions and museum collections. Hence the number “12-40” inscribed on this print of Elbow reflects that it was sent to subscriber number twelve. The original solicitation packet, sent to potential subscribers by Merle Armitage, includes this description:

“EWPOMC The Edward Weston Print of the Month Club / Because of your active interest in the work of Edward Weston, we feel that you should be among the first to be informed of an interesting project. The EWPOMC is a plan whereby those who are interested in and desire to own a representative collection of Edward Weston’s work may do so on a subscription basis for exactly one-third of the usual price, or $5.00 per print. Subscribers will be limited in number to 35. The first people to take advantage of this opportunity will receive each month a photograph selected by Edward Weston as the finest example of his current work. Each photograph will be numbered from 1 to 35 in an edition for subscribers only. Numbers starting with No. 1 will be given to subscribers in order of their response. Mr. Weston will reserve the right to 5 additional prints for exhibition purposes and museum placement. Photographs will be mailed to subscribers between the first and tenth of each month (starting in April) upon receipt of subscription price which is per month $5.00 plus tax in California, or by the year $50.00 plus tax in California, payable in advance.” [Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona]

[14] Op.Cit., Daybooks, California, 14 October 1931, p. 227.

[15] Ibid., California, 8 December 1932, pp. 265–266.

[16] The labels verso of this print of Zohmah and Jean Charlot relate to the following exhibition: The Photographic Society of America Invitation Salon, New York World’s Fair, Hall of Industry and Metals, New York, New York, 1–21 June 1940. Two Weston photographs were included in this exhibition: Zohmah and Jean Charlot (Conger 1473/1939) and Rubber Dummies (Possibly Conger 1440/1938). The New York venue was subsequently reorganized for travel as The Fifth Annual 100 Print Invitation Travel Salon of the Photographic Society of America 1941 which traveled to the following venues: Mezzanine Gallery of the Miniature Camera Club of New York, New York, New York, about 18 August–8 September 1940; Camera Supply Co., Long Beach, California, 10 December 1940–11 January 1941; 1941: Art Center School, Los Angeles, California, 13–29 January; San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, California, 1–23 February; U.S. National Museum, under auspices of the Arlington [Virginia] Camera Club, Washington, D.C., 1–30 March; Pasadena Public Library, Pasadena, California, 5–30 April; Fine Arts Gallery, San Diego, California, 3–30 or 31 May; The Art Barn, under auspices of the Salt Lake City Camera Club, Salt Lake City, Utah, 3–30 June; Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, 3–30 July; Milwaukee Art Institute, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2–30 August; Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, Memphis, Tennessee, 1–30 September; Society of Liberal Arts, [Joslyn Memorial, under auspices of Omaha Camera Club, Omaha, Nebraska, 3–31 October; Everhart Museum, Scranton, Pennsylvania, 1–30 November; Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2–31 December.

The following eleven additional venues, but not their dates, have been identified by exhibition labels adhered verso to this print of Zohmah and Jean Charlot: Cumberland Miniature Camera Club, Cumberland, Maryland; The Baltimore Camera Club, Baltimore, Maryland; Lantern and Lens Guild of Women Photographers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Kodak Camera Club of Rochester, Rochester, New York; Photographic Guild of Buffalo, Buffalo, New York; The Denver Lensmen, Denver, Colorado; The Camera Club of Bloomington, Bloomington, Indiana; The Queen City Pictorialists, Cincinnati, Ohio; Photographic Society of Quincy, Quincy, Illinois; The Canton Photographic Society, Canton, Ohio; Portsmouth Camera Club, Portsmouth, New Hampshire[?].

[17] Op.Cit., Daybooks, California, 3 December 1930, p. 198.

[18] Weston’s two related 1950 Paris exhibitions were held at the Galeries d’Art Kodak-Pathé from 23 January–15 February and the American Embassy from 20 February–3 March 1950.

[19] This Eindhoven exhibition was likely either Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel: Internationale Fototentoonstelling [Photography as a Means of Expression: International Photo Exhibition], held at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 5 April–4 May 1952 or Fotografie als Uitdrukkingsmiddel: Foto-tentoonstelling 1957-1958 [Photography as an Expressive Medium: Photo Exhibition 1957–1958], also held at the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, from 28 September–27 October 1957.

[20] [Promotional Brochure] [Edward Weston], Edward Weston Fiftieth Anniversary Portfolio: 12 Original Prints and A Personal Statement, [Carmel, California], 1951.

The second page of this promotional brochure, released in late 1951, notes: “… / This portfolio contains 12 prints for $100. / FOR FIFTY YEARS EDWARD WESTON HAS BEEN A PHOTOGRAPHER. / Last summer a group of friends came to him; now, they urged, was the time for him to choose the finest photographs, known and unknown, of his half-century’s work, and give a group of them the permanence of a portfolio. To help him in the labor of production they gave their services; others immediately subscribed with enthusiasm. The foreward [sic] by Weston was designed and printed by the Grabhorn Press. One hundred portfolios are now ready for immediate delivery.”

[21] The twelve photographs included in the Edward Weston Fiftieth Anniversary Portfolio 1902–1952 are: Cabbage Leaf (Conger 649/1931); Eel River (Conger 1155/1937); David H. McAlpin, New York (Conger 1662/1941); Eroded Rock, Point Lobos (Conger 637/1930); Nude (Conger 968/1936); Wall Scrawls, Hornitos (Conger 1504/1940); Guadalupe, Mexico (Conger 110/1923); Church Door, Hornitos (Conger 1505/1940); North Dome, Point Lobos (Conger 1806/1946); William Edmondson, sculptor, Nashville (Conger 1632/1941); “Willie,” New Orleans (Conger 1603/1941); and Dunes, Oceano (Conger 943/1936).

[22] “Biography” of “Edward Weston” on the Edward Weston & Cole Weston family website. See: https://edward-weston.com/edward-weston/

[23] Letter from Edward Weston to Donald Prendergast, dated 27 April 1950, 2 pages/1sheet, als, ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

[24] Letter from Edward Weston to Donald Prendergast, dated, 17 November 1950 1 page/1 sheet., als, ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

[25] Jacob Deschin, “Weston’s Legacy: Photography Is Richer For His Art, Integrity,” The New York Times, 5 January 1958, 18X.

Hi Paula,

Brilliant, well researched and informative article. Nice job! Thanks.

Two quick questions:. What does “not in conger” mean and what does “recto” mean?

Hope you are well and staying out of the path of this damned virus.

Cheers,

Ed Kelly

>>

LikeLike

Thanks for the compliments, Ed. Recto is a “term of art” that means front; verso means back. Not in Conger refers to the individual photograph number assigned by art historian Amy Conger in the book she compiled of the Edward Weston collection at the Center for Creative Photography: “Edward Weston: Photographs from the Collection of the Center for Creative Photography,” published in 1992.

LikeLike

An extraordinary and uplifting newsletter. Thank you, P&S for your generous dedication. Thank you, Paula, for your great work! Daile

>

LikeLike

Thank YOU for your comments, Daile. We’re happy you’re enjoying our posts and finding them useful.

LikeLike