“The photographer who stays at home has one great advantage over the photographer who travels—his familiarity with his surroundings. He can study his material constantly, know how it looks at different times of day and seasons of year. He knows when the light is best in all of his favorite places, when the weather will be good, what kind of clouds to expect.”[1] —Edward Weston. “Photographing California [Part II].” Camera Craft, March 1939

Note: Unless stated otherwise, all photographs illustrated in this post are currently owned, or were owned in the past, by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc. All photographs by Edward Weston © Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona.

“Weston on the Way” proclaimed The Carmelite on 26 December 1928: “Edward Weston is coming to Carmel for an indefinite stay, arriving early in January. He will occupy the Hagemeyer studio, with his son Bret [sic] Weston.”[2]

Long an intellectual and artistic community of great natural beauty, Carmel offered an ideal location for a creative individual like Weston. He would call it home for most of his life and gain inspiration there for many of his greatest photographs. Even today, an indelible link persists between Weston—man, work and Wildcat Hill home—and the special ethos of the Carmel region.

Weston quickly immersed himself in the town’s vibrant spirit after moving into his friend and fellow photographer Johan Hagemeyer’s studio sometime after 11 January.[3] Immediate praise for his photographs ensued. Both acclimation and acclamation are revealed in this “Personal Bits” notice in the 30 January 1929 issue of The Carmelite:

Roger Sturtevant’s birthday party last Saturday night proved two things,—first, the vitality of young Bohemia in Carmel; and the second, that rivalry by two artists in the same field can be superceded [sic] by mutual respect. / Eddie O’Brien and Roger in their black corduroys, with broad sashes about their waists. Tilly Polak in wine-colored velvet. All grades of formality and informality between. This freedom, absent of self-consciousness, is an expression of the individualism which is perhaps the chief charm of life in Carmel. / Edward Weston had brought with him by request a portfolio of his photographic work. / Roger Sturtevant makes a work of art of a group of fern-buds and a piece of broken glass. Johan Hagemeyer takes a bit of machinery and gives it majesty. Edward Weston puts a green bell pepper upon a milk bottle, or takes a part of a human torso. Looking at these photographs is re-discovering the world about us. Edward Weston’s work makes those who see it aware of beauty constantly before the eye, yet never before perceived.[4]

Another revealing description of Carmel’s influence on Weston, in the context of his October–November 1930 Delphic Studios exhibition in New York, appeared in the 2 October 1930 issue of The Carmelite:

Edward Weston has just sent fifty prints to New York. His show opens on October the fifteenth at the Dephic [sic] Studios on West Fifty- seventh Street. This exhibition of his photographic prints represents an immense piece of work for out of the fifty prints thirty-three were made in the year 1930. The balance, all but three shells and one portrait, were made last year. It is interesting, too, to know that all but three shells and the one portrait were made in Carmel. / Carmel can well be pleased with this excellent output from Edward Weston, the energetic worker. He works with dynamic power, exactness and quick decision. He arises early, works regularly, has time for a walk, meets people and takes care of home duties. He knows his course quite definitely and does not allow himself to be side-tracked. Carmel has not enticed him into the carelessness of its remoteness and its idyllic surroundings, nor has he been convinced that talking is ever a substitute for doing. / Therefore, from Carmel to New York will go clear, decisive, shiny prints of rocks and cypress details of Point Lobos; peppers, squash, bananas, cabbage, eggplant, celery from Espindolas; kelp from Carmel Beach; succulent from Sally Flavin’s garden; portraits of Jeffers and Perry Newberry. Fifty distinct, honest prints exposed in the twinkling of an eye by an artist and finished by the craftsman. The artist of this medium, photography, has no time to do over, scrape off or wait for a mood. He must have a 1930 decision. He must think as fast as the shutter winks or airplanes fly. All of his experience, his mental alertness, his creative impulse must go into that fraction of a second. / All good wishes fly to New York with this very distinctive and honest exhibit.”[5]

Carmel and environs may have provided Weston with artistic stimulation, but a sense of home and permanence proved more elusive. Indeed, the discontent and longing conveyed in his Daybook entry of 6 July 1931 is palpable:

Fog, thick, wet, has shrouded Carmel for almost two weeks. It has brought to me most definitely that this is no permanent place for me. Will any one place give me lasting interest, a home? Or any one woman? Strange question, the latter, following my recent love affair. But now is just the time to question. I do doubt my ability to remain for long in one place. The very nature of my work, requiring fresh fields to conquer. Or am I making excuses for a desire to change that has come over me? / I know that I have home-making instincts, yes, and marital ones. I should have a permanent home to return to — — and a wife — — to return to?[6]

Not long after he wrote this, Weston’s discontent would lift. Although he had been living and sharing a studio with Sonya Noskowiak since the spring of 1929, it was his meeting with Charis Wilson, at a concert in Carmel in 1934, that dramatically altered his personal life and effectively ensured his continued residence in Carmel. Their romance, ignited by photographic sessions at Weston’s studio, resulted in some of his most enduring images and led to both marriage and a productive collaborative professional relationship (Charis wrote much of the text for Weston’s books and articles).

Charis quickly supplanted Sonya in Weston’s affections and in his home. Following a hiatus in Santa Monica from Summer 1935 to Summer 1938 (a period which included travels for Weston’s first, 1937–1938, Guggenheim Fellowship), Edward and Charis returned to Carmel and Wildcat Hill. This time the return, at least for Weston, would be permanent.

Edward and Charis were sorely in need of a new residence and darkroom, having spent 1937 and the first half of 1938 processing Guggenheim negatives at Edward’s son Chandler’s cramped Los Angeles home. As Charis writes in Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston: “The good news [1938 Guggenheim renewal] arrived on March 27 … what we needed now was a real house and a good darkroom where Edward could make the most of his negatives and where I could begin turning the raw material of my log [of the Guggenheim journey] into a book.”[7]

The land on which this longed-for “real house and good darkroom” were built originally belonged to Charis’ father, famed author Harry Leon Wilson, whose substantial residence, Ocean Home, possessed a commanding view of the sea from its Carmel Highlands perch. Wilson transferred 1.8 acres of this property, across a ravine from Ocean Home, to Charis in 1938.[8] Like Ocean Home, the Westons’ new site enjoyed a spectacular ocean view.

Despite Weston’s periodic absences, Carmel clearly valued its ties with him and The Carmel Pine Cone happily announced his anticipated return from Southern California in its “Hither and Thither” column on 1 July 1938: “It looks very much as if we may expect to see Edward Weston home soon again. Niel [sic] is busy building a cottage and studio for him out at the Highlands; on the highway and next to Wildcat Canyon. He has absented himself far too long, say his friends.”[9]

Wildcat Hill must have seemed the realization of a dream, as Charis recounts:

Even before securing the title to our corner of the property, we sketched the building we wanted—one big room containing the living quarters, with a darkroom at one end and a fireplace at the other. Neil was just twenty-two at the time, but he was ready to act as architect, contractor, plumber, electrician, master carpenter, and bargain hunter for materials. A postcard from Edward to Ramiel McGehee dated June 1, 1938, sums up the situation: “House underway—foundation poured, floor laid. We leave for Motherlode this week. Neil is [doing] everything, a godsend. It will be close figuring but we’ll make it.[10]

Neil Weston (one of Edward’s four sons from his marriage to Flora Chandler Weston) commenced construction on the Wildcat Hill home and studio in early summer 1938. Evidently progress on the homestead advanced quickly, for that same summer Edward and Charis used it as a base for Edward’s second set of Guggenheim explorations. On 16 September The Carmel Pine Cone noted:

Edward Weston is about to leave for a sojourn in Death Valley to take further photographs of the western series he is doing on the Guggenheim Fellowship, and will be gone for about a month on the present trip. / During the summer months, the Westons have been moving in to their new home, at Carmel Highlands, taking occasional journeys into Death Valley, and being seen only occasionally in Carmel, Weston’s home several years ago. / Weston reports being able to make considerable strides forward in his present work, which deals with California scenery, especially mountain and sky effects.[11]

Neil diligently constructed the house; Charis and Edward transformed it into a Home. Charis elaborates on this transformation in Through Another Lens, My Years with Edward Weston:

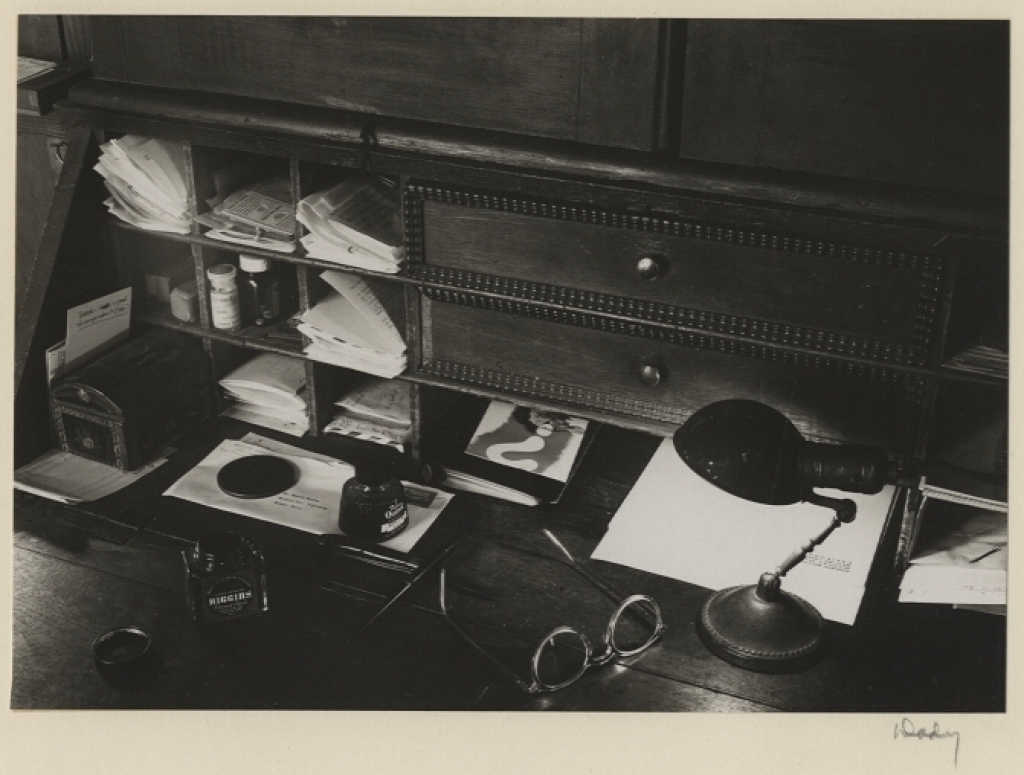

Neil had the darkroom and half the house completed by the time we returned, and he completed the rest soon after, for a total cost of $1,200, including $275 for his labor. With a main room that was 20 by 28 feet and had open rafters overhead, it felt royally spacious, even though it was only a board-and-batt shack in construction. The three glass-paned doors across the front faced the ocean, and skylight in the slanted room above provided a fine light for portraits. / The big room was sparsely furnished. Edward and I generally ate meals at the same black model stand Edward had had in Carmel, which was about the height of a coffee table. There were some spindle-back wood chairs. The old brown velour couch sat in front of the fireplace, and behind it stood the big solid wooden worktable with Edward’s dry mounting press on one end and, frequently, piles of prints being sorted for shows. Here we ate when we had company, after stacking up the prints. The double bed, covered with a Navajo rug, stood in the corner to the right of the fireplace. Edward’s desk, where he sat every morning to drink his coffee and write letters, and the rolling screen that we often pushed out into the yard as a backdrop for sittings completed the big furnishings. / … / The kitchen corner included an electric stove and a single-basin sink with dish shelves above it, a cupboard to the side of it for food and cookware, and at the end of it the coffee grinder. … / The house was on a hill above Wildcat Creek and Wildcat Canyon. Even though the post office preferred numbers, I cannily insisted on Wildcat Hill for our address because I knew from Carmel experience that a name would be remembered better by everyone, including the mailman. Edward and the boys resisted at first, so we ran the risk of being No. 168A Coast Road, but as I’ve said before, I was powerfully persuasive. / … / We had designed our new house with Edward’s photography in mind, including the showing of prints, but I soon realized that I needed a place to write. I took possession of what came to be called Bodie Room, after the brand name on its tiny wood stove. Bodie Room was behind the house in an outbuilding that Neil originally constructed for a garage … The best picture of it from the outside is My Little Gray Home in the West (1943). / … /.[13]

Charis also detailed the utilitarian but, for Weston, supremely satisfying specifications of the darkroom:

It’s true that the darkroom at Wildcat Hill was as spare as a darkroom can get—walls, shelves, sink, and drawers were all made of unpainted pine; there was no enlarger, since Edward made only contact prints; a bare, frosted bulb that hung on a cord from the ceiling served as a printing light, with a wooden clothespin to secure a larger or smaller loop in the cord to raise or lower the light; the tray of developer was kept at a constant temperature by being placed over a red lightbulb in a wooden box. A printing frame, some trays, a thermometer, 8×10 film holders, a few bottles of chemicals—and, of course, the three-minute egg timer.[14]

Following the conclusion of Weston’s 1938–1939, Guggenheim Fellowship, the next substantive interruption to life on Wildcat Hill came in 1941 with a commission from George Macy, director of the Limited Editions Club in New York, to travel cross-country photographing scenes and people for a deluxe new edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. But these were anxious times. Edward and Charis departed Carmel in May against the ominous backdrop of pending war, a country under an official state of emergency, and security restrictions in place at numerous “sensitive” industrial sites. They made it all the way to Maine and were in Wilmington, Delaware when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. By the end of January they were back home on Wildcat Hill. This would be Weston’s last extended stay away from Carmel.

Life in wartime Carmel brought both restrictions and responsibilities. Most difficult for Weston was the closure of Point Lobos which, as an area of strategic importance, left it off bounds to civilians for the duration of the war. As a result, Weston focused on subjects even closer to home. A prime example is The Cats of Wildcat Hill, published in 1947. The subject matter was Wildcat Hill’s own closely observed feline tribe.[16]

Geographic restrictions also led to a renewed emphasis on portraiture, primarily of Weston’s friends and family posed in or near the Wildcat Hill home.

Like citizens throughout the nation, Edward and Charis immersed themselves in civilian defense efforts. These ran the gamut from nurturing a Wildcat Hill Victory Garden (primarily Charis’s undertaking) to manning the local Yankee Point air craft warning observation post. Charis and Edward even participated in a Building Fund drive to enlarge and secure this station, thus improving its suitability for detecting any enemy ship and troop movements.[17]

In another volunteer effort, Weston presented a USO sponsored lecture on photographic technical problems to a group of servicemen, all of whom were experienced commercial photographers.[18]

Edward was clearly proud of these wartime endeavors, displaying his and Charis’ U.S. Army Air Force Observer and Air Raid Warden insignia, as well as sons Chandler’s and Cole’s U.S. Navy badges on a wall at Wildcat Hill.

Politics were on Weston’s agenda as well, particularly Franklin Roosevelt’s 1940 third term re-election campaign. But, undoubtedly, the most personal, significant and pressing of Weston’s concerns were his sons, all four of whom were serving in the military.

Weston addresses these various wartime factors in a 1945 letter to his friends Mona and Felipe Texidor[19]:

The war may have been omnipresent but it seems not to have greatly curtailed Weston’s professional ventures. Most notable was work on his major 1946 Museum of Modern Art retrospective. Preparations for this show included a visit to Wildcat Hill by Beaumont and Nancy Newhall during the summer of 1945, as reported in The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal on 22 June:

When Maj. and Mrs. Beaumont Newhall made their recent visit to the Edward Weston home in Carmel Highlands plans were completed for the photographic exhibit of several hundred of Mr. Weston’s pictures taken between 1902 and 1946 which is scheduled for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, during January and February of next year. / The work of Maj. Newhall, as director of the department of photography, has been taken over in a temporary capacity by his wife, who is also the librarian of the museum. The work of selecting the prints to be shown was undertaken as a part of a forty-five day holiday to the west coast which the Newhalls were enjoying after a three year overseas service just completed by Maj. Newhall.[20]

Another exhibition which commanded Weston’s attention was a show of approximately 102 photographs organized in 1942 by the United States Office of War Information for travel overseas in 1943. It opened at the Royal Photographic Society in London in June 1943, where, despite broader subject matter, it was titled California.[21]

Nor does the war seem to have significantly dampened Weston’s effervescent social life, as revealed in numerous accounts of visits to Wildcat Hill by family and friends. These included George Hoxie, editor of Minicam, fellow photographers Frederick Sommers and William Holgers, and dancer Maudelle [Weston] Bass, whom Weston had photographed in Carmel in 1939.[22]

War’s end naturally brought a tremendous sense of relief and liberation. That all four Weston sons survived their military service was certainly cause for celebration. Not surprisingly, post-war revelries at Wildcat Hill continued apace. Here, The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal describes one such jubilant gathering in August 1946:

Music, food, dancing and punch all blended to make a joyous reunion of the Weston family and friends at Edward Weston’s Studio at Wild Cat Hill, Highlands last Saturday Night. / Edward’s sons, Cole and Neal [sic] and Chandler’s son, Ted, sailed Neal’s ketch ‘Spindrift’ up from Los Angeles. Marie Grosup was also a member of the crew. / Others joining in the happy event were: Cole’s wife, Dorothy (who arrived several days before), Mr. and Mrs. Richard Lofton, Mr. and Mrs. Whit Wellman, Mr. and Mrs. John Short, Elizabeth Cass, Miss E.J. Clevinger, Miss Jean Kellogg, Miss Jennefer Lloyd, and Jehanne Bietry Salinger.[23]

Alas, the good times at Wildcat Hill were about to suffer dramatic reversals.

The first blow fell in November 1945 with the dissolution of Edward and Charis’s marriage. Although the relationship had been strained for a few years, its collapse startled many. In addition to the ensuing emotional turmoil came uncertainty regarding Weston’s continued residence at Wildcat Hill which, legally, belonged to Charis.[24] Initially, Edward returned to Glendale while she remained in Carmel. Fortunately, Charis appreciated how essential the home, darkroom and Carmel location were to Edward’s personal life and career and agreed to his staying on.

The decision involved difficult soul searching on both their parts. This is especially clear in an astonishing letter written on 18 November 1945 by Charis to Edward while he was in Glendale. In it, she definitively declared: “The house is yours from stem to stern.”[25]:

Charis would soon move away from Carmel and on with her life. On 14 December 1946 she married Noel Harris, a labor activist living in Eureka, California.

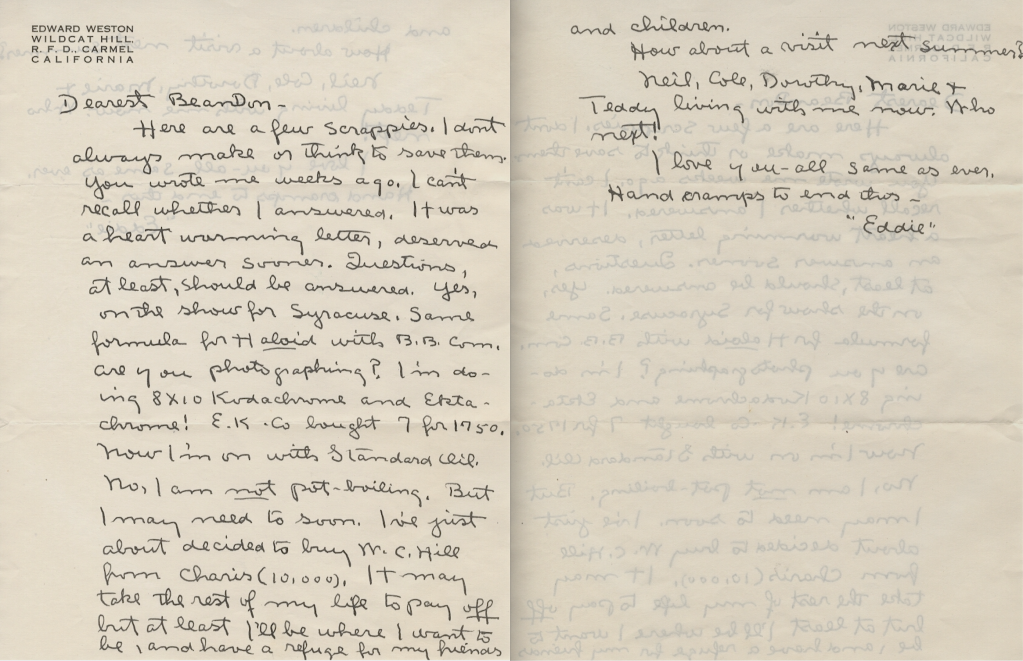

Weston’s continued residence was assured, but Charis still owned the house and land. Not content with his position as a tenant, Weston was determined to acquire the property, a resolution apparent in this 9 December letter to his friends Bea and Don Prendergast:

Dear BeanDon – / … You wrote me weeks ago. I can’t recall whether I answered. It was a heart warming letter, deserved an answer sooner. … I’ve just about decided to buy W.C. Hill from Charis (10,000). It may take the rest of my life to pay off but a least I’ll be where I want to be, and have a refuge for my friends and children. / How about a visit next summer? / Neil, Cole, Dorothy, Marie & Teddy living with me now. Who next! / I love you—all same as ever. Hand cramps to end this — / “Eddie.”[26]

A few weeks later, on 28 December, Weston announced that the down payment had been made:

“Dearest BeanDon / People are milling all around me. I would go quite mad if this went on. They mean well. I’m just getting old and grouchy. / But I do want to answer briefly and wish you a Happier than ever 1947. / … / Just paid 4000.00 down on Wild Cat Hill. Thank color [his Kodak project which appeared in publications during 1947 as “Edward Weston’s first serious work in color”]. / You-all come up and see me some time. / My hand cramps, so more a better day. / Eddy / with much love. / P.S. Looks as though Merle will do a E.W. book of 50 this autumn, my selections.”[27]

Despite the sense of dislocation and loss occasioned by Charis’ departure, Wildcat Hill continued as welcoming as ever with visits and social gatherings resuming their customary ebullience. Not surprisingly, Edward, with family and friends to lend support, bid farewell to the traumatic 1946 and ushered in 1947 with a suitable New Year’s Eve celebration:

Pulling no punches or Tom and Jerrys, Edward Weston and Mr. and Mrs. Cole Weston called their New Year’s Eve celebration a Bottle party. All the Westons were home. Brett and his daughter, Erica, came for the holidays as he is leaving shortly on his project of photographing the east coast for which he received the Guggenheim Fellowship. Neil Weston has returned from a jaunt to Los Angeles, and Mrs. Cole Weston’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. C.A. Herrman, from Vancouver, B.C., were there. …[28]

Costume parties reminiscent of past extravaganzas continued as well. Oh, to have been a guest at this particular February 1947 event where photographs by Edward and Cole served as prizes:

The costume party at Edward Weston’s Saturday night was a wild and wonderful affair with many more guests than had been expected and an extraordinary array of costumes. The men far exceeded the women in imaginative ingenuity it was generally agreed. / Cole Weston dressed as Dr. Livingtone-I-Presume complete with eye-glass, light beard, field hat, etc., was a convincing replica. Dorothy Weston, the hostess, wore a can-can costume with a green top, pink lace, purple stockings and bright colored garters. Edward Weston, in a brightly checkered clown jacket that reminded one of Harlequin, was quite fey. Neil Weston wearing an abalone diver’s mask, swim fins and diving underwear was frightening. …[29]

Of course, birthdays also provided cause for Wildcat Hill parties, especially when it was Weston being celebrated. This notice in the 2 April 1948 issue of The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal describes a gathering in honor of Weston’s 62nd:

To celebrate Ed Weston’s birthday, his four sons, Cole, Neil, Brett and Chandler, gave a birthday party for him at his home on Wildcat Hill in the Carmel Highlands Saturday night. Guests gathered around the punch bowl and enjoyed plenty of gay dancing. Among those invited to humor Mr. Weston, were: Mr. and Mrs. Richard Lofton, Marjorie and Frank Lloyd, Marie Short, and Jake Kenney.[30]

Wildcat Hill ownership and a degree of social normalcy had been achieved, but a truly incapacitating element—Parkinson’s Disease—was already exacting its degenerative toll on Weston’s health. The comments, “Hand cramps to end this” and “My hand cramps, so more a better day” concluding Weston’s above-quoted letters to the Prendergasts, foreshadow the insurmountable debility to come.

Weston’s nascent deterioration is apparent in photographs taken by Morley Baer to illustrate his wife Frances Baer’s article, “This Is Edward Weston.” Published in the April 1948 issue of U.S. Camera, Baer recounts her first meeting with Weston at Wildcat Hill, an illuminating description of Weston’s home, life and work.

To get to Wildcat Creek where Weston lives, one must pass through some of the most lush scenery ever offered in a travel folder. But the simple, one-story pine house I found on a ledge overlooking the Pacific was definitely no tourist attraction. There it was, a peaceful clearing in the coastal forest. A natural disorder of passion vine and nasturtiums wrapped themselves comfortably around the house, a tool shed, and the piles of cord wood nearby. ‘Beauty of the commonplace,’ hadn’t I read somewhere he said that? / When the door off the flagstone patio opened for me, I was grabbed by a surprisingly small man. He extended a hand and brought me into the one large room. He was no masterpiece of human construction, no strident westerner. Dressed in well-washed jeans and a wool shirt, he smiled at me kindly. My image was completely gone. This was Edward Weston. / With ease and congeniality, he introduced me to sons and friends grouped around the fireplace. … / It soon struck me that nothing in the house was merely decorative. The fireplace was for warmth and hot water (pipes lined its insides in what I understand is early Carmel tradition). There were chairs and stools to sit on, colorful Navajo blankets spread over the bed, kitchen essentials grouped in one rear corner, and book shelves and print cabinets lining one wall. The place seemed to have a beauty that came only from each part’s usefulness. / A few small, white cards caught my eye. They were tacked conspicuously to various parts of the room, and I had to inspect them immediately. Above the books in his desk (I noticed those on Strand, Sheeler, and Steiglitz [sic]) was a note of warning: / I do not lend books to friends. / I do not want to lose my books, / or my friends. EW / Over the telephone another one: Monterey Calls .05 / Please pay tax on / long distance calls. EW / My pre-Carmel idol has vanished. Eddie, a much more acceptable entity has taken his place. / … And, much later I discovered a particularly pointed message in the bathroom, placed where it couldn’t possibly be missed: / Arrow points to septic tank. / either treat it gently, or pre- / pare to pay the plumber. EW / Evidently this was an open house. But these direct messages indicated that it was not a house to be imposed upon by visitors. …[31]

The willing assistance of family, friends and colleagues helped Weston persevere through his increasing health travails. Although unable to photograph after 1948 (the year of his final photograph, Eroded Rocks, South Shore, Point Lobos), he remained productively engaged organizing exhibitions, preparing publications, supervising special printing projects, and entertaining visitors. He even participated in two acclaimed films: Willard Van Dyke’s 1948 Weston documentary The Photographer; and Louis Clyde Stoumen’s award winning 1956 film The Naked Eye.

The Photographer was a collaborative undertaking by Van Dyke and screenwriter Irving Jacoby. Produced by the United States Information Agency, it was filmed in 1947, copyrighted 1948 and entered broad release through the State Department in 1950.

As Weston wrote to Bea and Donald Prendergast in April 1950: “… / There is a documentary film now released by the State Dept. (USIS) called “The Photographer.” It is about me, I “play” the lead, and done by Willard Van Dyke. I recommend even though I have my face & form in it; you will see many familiar scenes, even the cats! / …”[34]

Screenwriter Jacoby wrote with great insight about Weston and his home in this publicity booklet for The Photographer:

… Here on the Pacific Coast such an artist lives and works. To understand photography with Edward Weston is an opportunity to learn a little about art itself. His house is simple. Where it is is more important to Weston than what it is.…He feels rich though he owns nothing but his tools, his personal effects, and his cats. In its [Weston’s home] ordered simplicity, in its uncluttered comfort. Here are the signs of a personality that is distilled out of a full, rich experience. The things around Weston’s rooms are all fragments of what he has seen and felt and known. / The beauty to be found in nature … Mexico …friends.…[35]

Another fascinating account of life at Wildcat Hill during this period was written by photographer and filmmaker Louis Clyde Stoumen, whose Oscar winning 1956 documentary The Naked Eye featured Weston. Published (regrettably without illustrations) in the June 1948 issue of Photo Notes, it reads, in part:

One of the world’s greatest living photographers lives simply in a one-room frame house perched on a height overlooking the Pacific Ocean near Carmel, California. A rough darkroom, cooking facilities and a toilet-shower are built into one end of the house. It has electricity, plumbing and a telephone, but its only comfort against the coastal damp and cold is a small fireplace. / Edward Weston’s other possessions include an old-fashioned desk, a bed, cameras and lenses, a few hundred books, cabinets jammed with a lifework of negatives and prints, about a dozen cats, a few chairs, and a treasured litter of organic and art objects such as shells, gourds, Mexican bowls, paintings, twisted tree roots, bleached bones, and sculpture in wood, ceramics and stone. / The house, built for him ten years ago by his son Neil, is constructed of a single thickness of pine boards. It is surrounded by huge trees. A small skylight is built into its pitched roof. From his windows Weston can look out on the sea…[36]

Ever one to delight in sharing both his photographs and his expertise, Weston continued to welcome students to his Carmel home. This willingness took official form in 1948 and 1949 when he served as a “Visiting Instructor of Photography” for Summer Session students of the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute). The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal describes the 1948 classes:

About three weeks ago ten or twelve members of the summer classes in photography of the California School of Fine Arts made a safari to the Highlands to Edward Weston’s workshop for instruction from Mr. Weston, the famous photographer now being a member of the faculty of that school. Instead of the teacher going to the pupils, which is generally the case, the students come down to Mr. Weston’s. The sessions last four days and include theory and actual doing. An excursion is usually taken to Point Lobos for shooting, and print sessions are held in the evening. Each group that comes is new and Mr. Weston limits the number of pupils to twelve. The classes (of which two so far have been held) are proving to be so successful that the plan will continue through the fall session.[37]

Minor White captures the vitality of these Point Lobos Summer Session excursions in his article, “A Unique Experience in Teaching Photography,” published in Aperture magazine in 1956.

The climax of every year was the five day, early spring trip to visit Edward Weston and to photograph at Point Lobos State Park which his pictures have made famous. Full-time concern with photography was nothing new with us, but on this trip the intensity rose like a thermometer held over a match flame. / Until he became too ill, Weston showed us the beauties of the park itself. He made the students leave their cameras in the cars the first afternoon knowing full well that otherwise they would have all gone to work in the first hundred yards. He annotated one magnificent spot after another, always stopping at the ancient Cypress stump he photographed first in 1929. Under his guidance the years ticked by a picture at a time. It slowly dawned on us that this rich place was a little like a lumber yard to him, stocked with the material for a million pictures. From the depth of his honesty he said that he but scratched the surface and encouraged everyone to do more. / This first contact with the man and the place was rounded off that same evening. After dinner in nearby Carmel or Monterey the group drove to Weston’s cottage to see the man and his photographs. The single flood lamp was rounded up, a brighter bulb put in and Weston took out a stack of prints from their cases. He selected carefully, put them, one at a time, on the spotlighted easel.…[38]

Weston also found time to hold less formal photography discussions at Sunday gatherings at his home. As with visiting students, he showed a cross-section of his work on an easel, spoke about the photographs briefly and encouraged comments from his guests.[39]

Personal projects continued from the late 1940s through the early 1950s as well. In 1947, Merle Armitage’s handsomely designed book 50 Photographs by Edward Weston appeared. In 1950 the beautifully illustrated My Camera on Point Lobos was published. It included a foreword by Weston in which he comments: “Here in Carmel I can work, and from here I send out the best of my life, focused onto a few sheets of silvered paper.”[40] 1950 also brought solo exhibitions in Paris and New York;[41] and in 1951 the Edward Weston Fiftieth Anniversary Portfolio 1902–1952 was released. In addition, the Project Prints enterprise was in full swing between 1950–1952. This ambitious undertaking resulted in the printing of 830 photographs, each in an edition of six (later increased to eight), selected by Weston and ultimately printed under his supervision by Brett between 1952–1955.

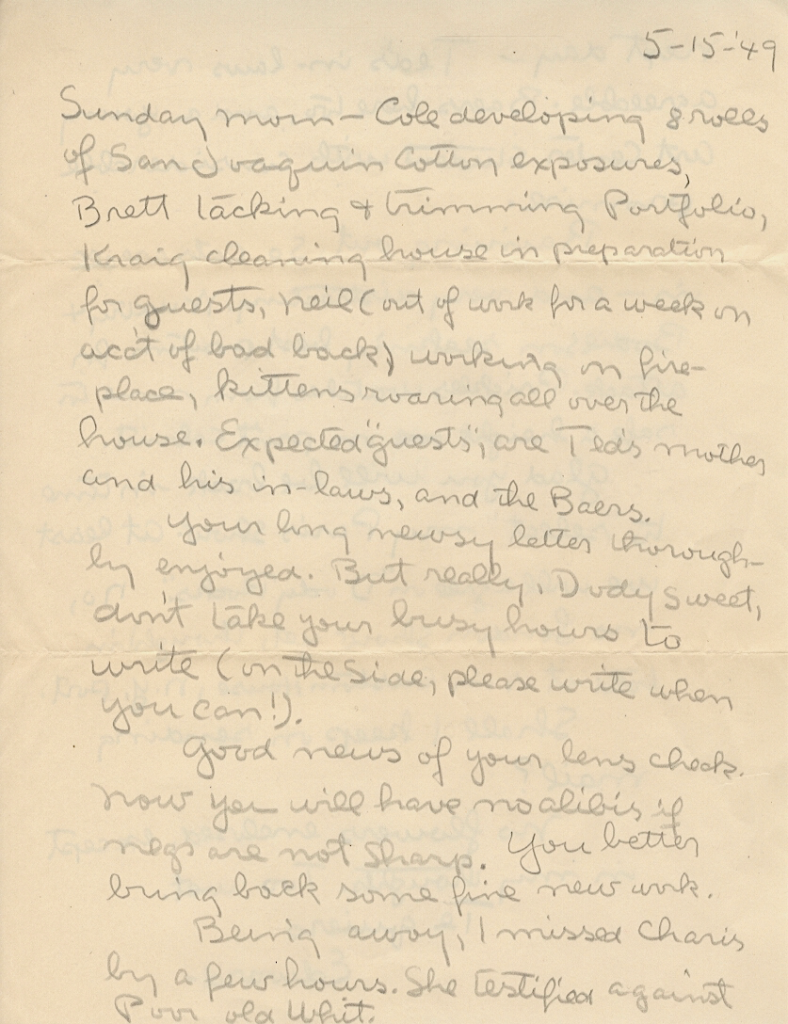

In his letter of 16 May 1949 to Dody Thompson, his one-time student, assistant and eventual daughter-in-law (she married Brett in 1952), Weston captured the frenetic activity at Wildcat Hill:

Sunday morn – Cole developing 8 rolls of San Jaoquin cotton exposures, Brett tacking & trimming Portfolio, Kraig cleaning house in preparation for guests, Neil (out of work for a week on acc’t of bad back) working on fireplace, kittens roaring all over the house. Expected “guests,” are Ted’s mother and his in-laws and the Baers. / … / Next day – Ted’s in-laws very agreeable. Baers here too, and a young art center student with considerable promise. / Raining out, so cats are all in – and very distracting. Wuxtry & Bodison seeking best position for attack. Prickles watches from none too safe a height on print cabinet. / Glad you will be back in time to “select” my Paris show. At least we will agree on “Dody Rocks.” No, no London show yet, though I’m told it is in Custom House, N.Y. port. / Shall I keep on sending mail? / No flowers enclosed, except in my thoughts. Too wet. / Te quiero / Edward–”[42]

(Christie’s: An Eclectic Eye, 18 September 2016, Lot 59)

Guests arriving at Weston’s doorstep continued to receive a gracious welcome, despite his increasing infirmity.

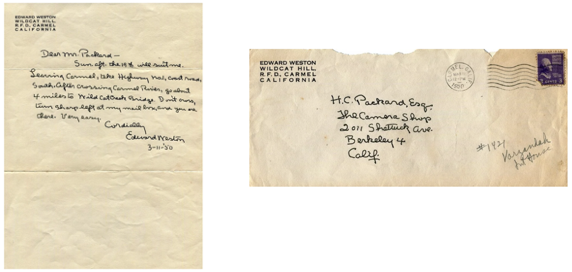

A 1950 visit from H.C. “Chappie” Packard, a photography enthusiast and owner of The Camera Store in Berkeley, set the stage for a friendship which resulted in an exhibition of Weston’s Fiftieth Anniversary Portfolio at The Camera Store in January 1952. Below are directions Weston sent to Packard on the occasion of his first excursion to Wildcat Hill.[43]

Long-time friend and colleague Nancy Newhall visited in December 1952, possibly to continue assisting Weston with editing his Daybooks for publication.[44]

Another guest was journalist Jacob Deschin, Camera Editor for The New York Times, who wrote, in part, of his visit to Wildcat Hill in the 30 August 1953 issue of that newspaper:

Nearing the house, a building of simple construction, we were pleasantly surprised to see in the midst of this display a cylindrical print washer operated by water from a faucet. At first it seemed out of place but, on second thought, entirely appropriate. The prints in the washer were Brett Weston’s, the photographer’s son, and already an accomplished worker in his own right. / He greeted us at the door and escorted us into a large and what seemed like almost a vacant room. Weston’s desk, a huge table for handling prints, a few chairs, little more—or such was the immediate impression…[45]

Beaumont Newhall describes the warm welcome Weston accorded photography aficionados in the August–September 1954 issue of Infinity.

At Wildcat Hill, on the California coast just south of Carmel, there is an attractive redwood one-story building. It is the home, the studio, and the darkroom of Edward Weston. For years the latch string has always been out for anyone interested in photography. If you have been fortunate enough to look at prints with Weston, you will never forget the experience. One by one the beautifully mounted prints are put on a well-lighted easel for you to look at as long as you want to. Weston is always ready to answer your questions, to discuss the pictures—or to keep silent. / To make a selection from what you have seen—if you have come today to buy—is always difficult. But Weston never hurries you, and lets you put aside your favorites and go over them again and again until finally the pile is reduced to what your pocket book can afford. At the end of the day you have acquired more than photographs—you have learned about photography. You have come in contact with one of America’s greatest photographers. You have become aware of a philosophy towards photography—and towards life. / Almost inevitably the talk will turn to Weston’s legendary technique. You soon learn that his preference for the 8×10 view camera and for printing by contact on glossy paper is not an arbitrary restriction. Weston’s technique is personal, arrived at from years of experience and experiment. It is an integral part of his style..[46]

Painfully evident in the Rosario Mazzio photograph illustrated above, by 1954 the progression of Weston’s Parkinson’s Disease was making movement and speech exceedingly difficult. Lovingly cared for by his sons, he finally succumbed at his Wildcat Hill home on New Year’s Day, 1958. Appropriately enough, he is reported to have died sitting in a chair facing the sunrise.[47] As Amy Conger movingly conjectures: “When he sat outside on the porch early in the morning on the first day of 1958, maybe he could see and hear the ocean; the pines, rocks, wind, and maybe a cat were [sic] there when his heart finally stopped.[48]

NOTES

1 Edward Weston. “Photographing California [Part II],” Camera Craft 46:3, March 1939, 98–105.

2 “Edward Weston on the Way,” The Carmelite 1:46, 26 December 1928, 2. Johan Hagemeyer’s studio was located at Mountain View and Junipero avenues in Carmel.

3 “The Village News-Reel: Edward Weston, photographer, will occupy the Johan Hagemeyer studio…” The Carmel Pine Cone 15:1, 4 January 1929, 15. This brief notice reads: “Edward Weston, photographer, will occupy the Johan Hagemeyer studio at Mountain View and Junipero avenues after the eleventh of the month.”

4 “Personal Bits,” The Carmelite 1:51, 30 January 1929, 3.

5 Hazel Watrous [H.W.], “Carmel to New York,” The Carmelite 3:34, 2 October 1930, 11. [2 Illus.]

6 Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, vol. 2, California, ed. Nancy Newhall (Millerton, N.Y.,1973), 6 July 1931, p. 261.

7 Charis Wilson and Wendy Madar, Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, New York: North Point Press / Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998, Chapter 10, p. 178.

8 Ibid., Chapter 11, p. 185.

9 Ida Newberry, “Hither and Thither: It looks very much as if we may expect to see Edward Weston home…,” The Carmel Pine Cone 24:26, 1 July 1938, 16.

10 Op cit., Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, Chapter 11, p. 186.

11 “People Talked About: Edward Weston is about to leave for a sojourn in Death Valley…,” The Carmel Pine Cone 24:37, 16 September 1938, 3.

12 Despite Hurrell’s date and inscription on this and related Hurrell portraits taken at the same time, they cannot have been photographed in the Wildcat Hill studio in 1937 since construction on it did not begin until 1938. Weston and Charis were still based out of Southern California in 1937. A probable date of 1939 is indicated by an entry in Weston’s Wildcat Hill guest book which Hurrell signed: “George Hurrell 1939.” Hurrell may have inscribed and dated these vintage prints at a later date, well-remembering his visit but mis-remembering the year. I am exceedingly grateful to Gina and Kim Weston for reviewing Weston’s guest book on my behalf and supplying an image of the relevant page.

13 Op cit., Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, Chapter 11, pp. 188–190.

14 Ibid., Chapter 14, p. 222.

15 “Fellowship Winner Is Entertained: Edward Weston, Wife Pause Here On Long Cross-Country Trek,” Phoenix Gazette, 18 June 1941, page unidentified.

This account of a visit by Edward and Charis to Arizona and their stay at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Archer E. Linde in Phoenix, Arizona, reads: “The Guggenheim Fellowship has been awarded to outstanding persons in several fields, but the only photographer to win it has been a Phoenix visitor for the past three days. He is Edward Weston, and so great an authority on the subject of pictorial art is he that he was engaged to write the revised article on photography for the Encyclopaedia Britannica. / His wife, Charis Wilson Weston, is with him. Professional ghost writer and author of many periodicals in her own right, she is the daughter of the late Harry Leon Wilson, who wrote such famous stories as ‘Ruggles of Red Gap,’ ‘Merton of the Movies’ and ‘Bunker Bean.’ / The two, who have been the house guests of Mr. and Mrs. Archer E. Linde, are on a seven months’ tour of America now, being under contract to a New York publisher, of the ‘Limited Editions’ club, to do the illustrations for a special edition of Walt Whitman’s ‘Leaves of Grass.’ They will cover most of America in search of proper scenes. / They completed a book of their own, ‘California and the West,’ during the two years immediately following receipt of the fellowship, in which time they covered 25,000 miles, mainly in California, and Mr. Weston took 1,200 pictures and made large prints of each. / In addition to scenes sought for the Walt Whitman edition, they plan to collect more material for another travel tale of their own on this present trip. / The couple, who have been married eight years, have their headquarters in Carmel, Calif. / So famous is Mr. Weston as a photographer, that he was the subject of a book, ‘Edward Weston’ written by Merle Armitage some years ago. / The couple left yesterday for Tucson, en route to the Old South.”

16 For a detailed examination of Weston and his cats, see Edward Weston Bibliography Blog post of 12 October 2019: “The Big Meow, The Weston Cats”: https://edwardwestonbibliography.blog/2019/10/12/12-october-2019-the-big-meow-the-weston-cats/

17 For information on these Building Committee activities, see: “To the Editor: Pine Cone Cymbal,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 28:36, 4 September 1942, 6.

This letter reads: “TO THE EDITOR: / PINE CONE CYMBAL. / With winter approaching, it is necessary to build a larger, more secure observation post at Yankee Point, which will increase the efficiency of the post and the comfort of the observers. Financial assistance is needed. We are asking the members of this community to contribute whatever is possible. / You are aware of the vital part played by the Ground Observation Corps in this critical hour. We keep the Army constantly informed of all plane and ship movements, protecting not only the homes in our community but the Pacific Coast. / Neither the Army, Civilian Defense, nor any other organization has the funds to build an observation post, which will cost $200 to $300. / The Building Fund is in charge of Mr. Hugh Van Swearingen, Treasurer, Box 99, Carmel Highlands. Any contribution anyone can make toward this purpose will be sincerely appreciated, not only by the Building Committee, but by all the observers. Sincerely, / YANKEE POINT BUILDING COMMITTEE / Whit and Olga Wellman (Charge of Post) / Mrs. Charles Bigelow / Mrs. Edward Weston / Mr. Hugh Van Swearingen, Treasurer.”

and

“Post Built by Volunteers I Almost Finished,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 28:45, 6 November 1942, 7.

18 “Pine Needles: Edward Weston Gives Talk,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 30:5, 28 January 1944, 13.

19 Correspondence: Edward Weston to Mona and Felipe Texidor, n.d. [1945]; als in ink; 6 pp/3 sheets; Envelope: Postmark torn, envelope tattered, but signed with address on reverse. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.) This letter reads, in part:

… You may well ask why the 4 months delay in writing you a letter already started? A very busy life of war duties, earning a living, writing four boys in service, may be the answer — but not entirely. I have a psychological barrier; I know that if I wrote you every day in the week I would not scratch the surface of untold happenings, that my real desire is to see you face to face, to embrace you —. / I understand from Rafael that you lost a child. Does that mean two deaths? And you have one? a boy? My dear friends, you have had much grief. And I have had such good luck, with four boys, two grandchildren, alive and well in the midst of this holocaust. Neil is in Army Transport Service, on a 90 ft. ocean-going tug-boat “at sea” on the Pacific; last letter from N. Guinea. Chan is Navy, S. Diego, Cole is Navy, Okla. Brett, Army, Signal Corps, (Ltd. Service) N.Y. / I lost two of my dearest friends within a year of each other; Ramiel who died last Dec. (1943), and Tina. Of Tina I had heard nothing for many years. Her death in Mexico was strange and sudden. You may know more about it than I do. Did you see her? / We have been active in the war effort in ways suited to our life and location. I was air raid warden, Charis drove U.S. Mail. We were both in Air Craft Warning Service; Charis practically ran our local post, and I took a lonely night vigil (because I was lazy mentally, didn’t want to go to school and learn all planes!) We have had a large V[ictory] garden; peas, beans, corn, broccoli, rhubarb, potatoes, tomatoes, chard, asparagus, strawberries, beets, carrots, cauliflower, etc. etc. But one of my greatest war efforts has been in writing of letters of praise or blame to Congressmen, radio commentators, newspapers, magazines. And it pays big dividends. We worked hard on the election, pro-Roosevelt of course; joined the National P.A.C., electioneered in the foothills, had a very exciting time. I cast my 4th vote for F.D.R. / Do you remember “Pirracas”? What a cat! We have 16 cats now! My recent photographs have been of cats. Hard to believe. Of all my friends who have not seen my recent work, I would rather that you two had a week and a few thousand examples to view. / I could go on and on, how we have two acres, overlooking the ocean, all paid for, how the house was built by Neil, how I’m going to have the most important show of my life this coming Dec. at Museum of Modern Art New York, — a retrospective, 300 photographs 1902-1945. …

20 Barbara Curtis, “Pine Needles: Plans Made,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 31:25, 22 June 1945, 10.

21 “Lecture Programme: Exhibitions At Prince’s Gate.” The Photographic Journal [The Official Publication of The Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain and The Photographic Alliance] 83 (June 1943): 244.

This entry, under the “Lecture Programme” column in the “Announcements” section of The Photographic Journal reads: “Exhibitions At Prince’s Gate / Friday, June 4th to Saturday, June 30th (1) Group Members’ Exhibition; (2) Prints of Spanish Cathedrals and Churches, by J.R.H. Weaver, M.A., President, Trinity College, Oxford; (3) American Office of War Information. ‘California,’ by Edward Weston.” NOTE: This same listing appears again in the July 1943 issue of The Photographic Journal, page 282. This listing reads: “Exhibitions At Prince’s Gate / Friday, June 4th to Saturday, June 30th. Prints of Spanish Cathedrals and Churches, by J.R.H. Weaver, M.A., President, Trinity College, Oxford; American Office of War Information. ‘California,’ by Edward Weston.”

22 For articles in The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal remarking on these visits, see: (1) [George R. Hoxie, possibly], “A Swing Around the Country with Edward Weston,” Minicam Photography 9:4, December 1945, 75–83. (2) Irene Alexander, “Pine Needles: Frederick Sommer Visits Westons,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 30:8, 18 February 1944, 9. (3) 29 Irene Alexander, “Pine Needles: Noted Dancer Visits,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 30:22, 26 May 1944, 8. (4) 31 Irene Alexander, “Pine Needles: Berkeley Visitors,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 30:34, 18 August 1944, 8.

23 “Reunion at Weston’s,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 32:31, 2 August 1946, 16.

24 Op.Cit. Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, Chapter 22, pp. 351–352. Here, Charis discusses and reproduces the property settlement that divided the land, house and personal belongings. The Minicam issue Charis refers to is: [Hoxie, George R., possibly]. “A Swing Around the Country with Edward Weston.” Minicam Photography 9:4 (December 1945): 75–83. [14 Illus.]

25 Correspondence: Charis Wilson Weston to Edward Weston, dated 18 November 1945; tl, with Wilson’s initials, “ch,” typed in lower case, at the close of letter; 2 pp/2 sheets; both sheets on “EDWARD WESTON / WILDCAT HILL / R.F.D., CARMEL / CALIFORNIA” letterhead. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.) This letter reads:

Dear Edward: Your letter makes me realize I have been up to my old trick of trying to put myself in your place and do your thinking for you. I’m sorry if I was preaching at you: I didn’t mean to do that. / You say “awaken to a picture of yourself.” Do you imagine I have not been scanning that picture in all its bitter, gruesome, details, for the past month? And do you imagine that has been a pleasant pastime? My problem is simply to learn how to live like a decent human being—to be my own rock of Gibralter—and it is going to take hard work to do it. The reason I wrote as I did about you and your plans, is that I have enough sins to account for already, and I cannot bear the idea that in working them out I should be doing further harm to you. / “The house is yours from stem to stern” still goes. I have not reversed myself. If you want to live here and can live here, I think you should. My doubts on the practicability of it for you were the doubts of that part of me that still stays married to you in my thinking: I don’t like to see you in a position of dependence on others for your basic necessities of daily live. / I asked you to think carefully about it before deciding and even as I asked, I realized that it would be impossible for you to do it there. / Please understand, Edward. I have been going through a difficult upheaval: a reexamination of all my actions, ideas, ways of thinking, trying to find myself and to establish—not to ‘get back to’, because I have never had one—a normal way of life. While I was in the midst of this, I could not see you; for many reasons, but the main one: I have loved you very deeply, and beneath all the wreckage and mess that our union has generated, I still love you. But since we are so ill-adapted to living together, I must force myself to put that love in its proper place in relation to the rest of of my life and activities. And, perhaps because I have become a weak character, I could not do that with you near me. / Now the worst of it is over. There is a long road ahead, much work yet to be done, but at least I am reasonably prepared to face it and getting my feet on the ground. / So let’s begin again on the house, property, arrangements, and do it properly. Your letter sounded as though I were pitching you out on your ear, like a Mrs. in the funny paper. It’s yours to decide as much as mine, and we should be able to work it out in a way that satisfies both of us. We can’t do that on a basis of saying “now that I know your desires.” / If you think the best and quickest way to get it settled is to come up here now, and talk things out here, then come ahead. I am sorry about being so fierce on the “come to move in or move out” subject, but I was desperately glaring at the amount of work ahead, the little time for doing it, and the need to know whether it will be I who move out or you, so I can really settle down to continuous work. / I desperately didn’t want to see you again until I had some problems worked out clearly enough to feel sure of myself. But I am straightened around enough now that I would rather see you at once than feel that you were only agreeing to my dictates on how to handle things. This is the last thing I want. / CH / The kitty bubbles came today and I and the younger generation are mad about them. Older cats look amazed and distrustful. Also today, more than a dozen more copies of Minicam.[33]

26 Correspondence: Edward Weston to Bea and Donald Prendergast, dated 9 December 1946; als, in ink, on printed Wildcat Hill letterhead; 2 pp/1 sheet; Envelope: Postmarked Carmel, California 12.9.46 with printed “EDWARD WESTON / WILDCAT HILL / R.F.D., CARMEL / CALIFORNIA,” return address on the envelope. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

27 Correspondence: Edward Weston to Bea and Donald Prendergast, dated 28 December 1946; als, in ink; 1 pp/1 sheet; Envelope: Postmarked Carmel, California 12.28.46 with no return address on the envelope. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

28 Sara Farrar, “Pine Needles: Bottle Party,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 33:1, 3 January 1947, 9.

29 Sara Farrar, “Pine Needles: Weston Costume Party,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 33:8, 21 February 1947, 15.

30 Zoe Kernick, Zoe, “Pine Needles: Ed Weston Birthday Party,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 34:14, 2 April 1948, 12.

31 Frances Baer, “This is Edward Weston,” U.S. Camera 11:4, April 1948, 16–19, 54. [10 Illus.]

32 Bruce Ariss, ed., The Story of Carmel: A Handbook for Natives and Tourists. Monterey, California: What’s Doing, Inc., September 1948. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

33 Willard Van Dyke, “Many Talents for a Complex Art,” Infinity, June–July 1953,: 4–5. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

34 Correspondence: Edward Weston Bea and Donald Prendergast, dated 27 April 1950; als, in ink; 2 pp/1 sheet. Envelope postmarked Carmel, California April 27, 1950 with no return address on the envelope. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

35 Irving Jacoby, “The Commentary,” In The Photographer: From a Motion Picture About Edward Weston [by Willard Van Dyke], Monterey, California: W.T. Lee Co., n.d. [after 1950] (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

36 Louis Clyde Stoumen, “Week-end with Weston,” Photo Notes (June 1948): 11–14. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

37 “Weston Continues Teaching.” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 34:34 (20 August 1948): 4.

38 Minor White, “A Unique Experience in Teaching Photography,” Aperture 4:4, 1956, 150–156.(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

39 For a description of one of these informal Sunday gatherings, see: 51 “Hollywood and Vine,” Modern Photography [14:2] (February 1950): 20. This article reads, in part: “Edward Weston holds open house every Sunday at his Carmel home for the purposes of informal discussions of photography with friends and admirers. We went out last Sunday to see what it was like, and found Weston in the big living room, seated beside an easel on which he displayed a print. For two hours we watched him display a cross-section of his work, and listened to his stimulating comments and the criticism offered by visitors. / …”

40 Edward Weston, My Camera on Point Lobos: 30 Photographs and excerpts from E.W.’s Daybook, Yosemite National Park: Virginia Adams, Yosemite National Park and Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

41 The Paris, London and New York exhibitions were:

Paris: Galerie d’Art Kodak-Pathé [Organized by Daniel Masclet and Group XV], Daniel Masclet présente Edward Weston, Paris, France, 23 January–15 February 1950 (Solo). [Original venue for exhibition with subsequent showing at American Embassy Annex, Paris under auspices of Services Américains d’Information Paris, 20 February–3 March 1950 (to supplement the European film premiere of the Voice of America’s The Photographer by Willard Van Dyke)].

and

New York: New York Camera Club, New York, New York, [75-print show of Edward Weston photographs] late February or early March–31 March 1950.

42 Correspondence: Edward Weston to Dody Thompson, dated 16 May 1949; als, in pencil; 2 pp/1 sheet; Envelope: With printed “EDWARD WESTON / WILDCAT HILL / R.F.D., CARMEL / CALIFORNIA,” return address, addressed, “Dody Warren / c/o M. Malsman / 289 Washington / New Haven / Conn,” in black ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

43 Correspondence: Edward Weston to H.C. “Chappie” Packard on printed Wildcat Hill letterhead, dated 11 November 1950; als in black ink; 1 p./1 sheet; Envelope: With printed “EDWARD WESTON / WILDCAT HILL / R.F.D., CARMEL/ CALIFORNIA,” return address, addressed, “H.C. Packard, Esq. / The Camera Shop / 2011 Shattuck Ave. / Berkeley 4 / Calif.” in black ink; Postmarked “CARMEL CALIF. 1950 / MAR 11 / 12-PM” (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

This letter reads: Dear Mr. Packard— / Sun. aft. the 19th will suit me. / Leaving Carmel, take Highway No. 1, coast road South. After crossing Carmel River, go about 4 miles to Wild Cat Creek Bridge. Don’t cross, turn sharp left at my mail box, and you are there. Very easy. / Cordially / Edward Weston / 3-11-’50”

44 Virginia McGrath, “Pine Needles: Edward Weston Has Guest,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 37:49, 7 December 1951, 12.

This article reads: “A visitor this week in the home of Edward Weston at Carmel Highlands is Mrs. Beaumont Newhall of New York City. During the war Mrs. Newhall took over the Museum of Modern Art’s department of photography, which was founded and supervised by her husband, Beaumont Newhall, now curator of George Eastman House, only museum and gallery in the country exclusively devoted to photography. Mrs. Newman writes on photography and arranges many of the activities that center at Eastman House.”

45 Jacob Deschin, “Weston At Home: A Visit With the Famous Carmel Photographer,” The New York Times, 30 August 1953, X13.

46 Beaumont Newhall, “Edward Weston,” Infinity, August–September 1954, Cover, 3, 7.

47 Op.Cit. Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, Chapter 22, p. 359.

48 Amy Conger, Edward Weston: Photographs from the Collection of the Center for Creative Photography, (Tucson, Arizona, 1992), p. 45.

Thanks, Paula. Nice work! Cheers, Ed Kelly

Hope you are well and staying safe.

>

LikeLike

Thanks, Ed!

LikeLike

I’ve never understood the statement by Charis that Edward died “facing the sunrise.” If he was sitting on the porch, he would have been facing west toward the ocean with the sun rising over the hill behind the house. The sun wouldn’t have been visible from the porch until it was high in the sky. As a long-time Weston fan, I really enjoy these very well-researched and -written posts. Thank you for providing them!

LikeLike

?Thanks so much for this, Paula – did I ever tell you that we have one of the studio signs that supposedly hung on the mailbox in the Lane Collection? Hope all’s well with you – Girl with Riding Crop is being sent to MFA this week – hooray!

_____ Karen E. Haas Lane Senior Curator of Photographs Museum of Fine Arts, Boston khaas@mfa.org

The MFA is currently closed and staff are working remotely ________________________________

LikeLike

Hi Karen, so glad you like the post, big compliment coming from you! How superb that the MFA has one of the studio signs, it would make a terrific addition to a Weston exhibition. Hooray indeed about Girl with Riding Crop!!! You know I’m as thrilled about this as you are.

LikeLike