(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc. ©1940, Nancy Newhall, ©2019, the Estate of Beaumont and Nancy Newhall. Permission to reproduce courtesy of Scheinbaum and Russek Ltd., Santa Fe, New Mexico)

“I have done some good Pussygraphs…”

—Letter from Edward Weston to Bea and Don Prendergast, 20 September 1944 [1]

It is a truth universally acknowledged that Edward Weston and Charis Wilson were true blue, dyed-in-the-fur cat aficionados. Fortunately, life on Wildcat Hill afforded the perfect breeding ground, both for Weston’s photographic exploration of feline form and the cats’ own instinctual behavior. As Weston commented to a journalist for The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal, “We both loved cats all our lives, but Wildcat Hill gave us our first opportunity to have them in wholesale quantities.”[2] Wholesale indeed. By some accounts that number varied over the years from as few as two to more than twenty.

The Wildcat Hill experiment proved fulfilling but problematic, posited as it was on the theory that allowing cats to interact largely on their own would give rise to a colony of naturally behaving kitties. In her “Introduction” to The Cats of Wildcat Hill, Charis Wilson wrote:

It all began in 1938 when we built our own house on the California coast five miles south of Carmel. We had had single cats before then, but we had always wanted to have several at one time—first, because we liked cats, and second, because we were interested in their behavior. In those days it was my contention that a single cat became too humanized from always associating with people; that observations of its habits and behavior would tell you more about the family it lived with than about the cat itself; that only a cat whose associates were other cats would behave in a naturally catty manner. / At last we had ample range to support quite a colony of cats—nearly two acres of land on a bluff above the coast highway. … If we visualized any limit to the project in the beginning, we probably thought of having eight or ten cats. When production once got under way, the census of our cat society rarely fell below twelve and frequently rose above twenty. It was not long before the flaw in my “cats should associate with other cats” argument, became apparent. We soon found that the cats themselves considered it unnatural—or at least highly undesirable—to have a lot of other cats around. Only our constant vigilance could keep the group from being broken up and dispersed. / … / Aside from maintaining the group, we found it necessary to regiment the cats to some extent, so that we too could continue to live on the premises. A reasonable standard of indoor conduct had to be enforced, and the methods for achieving this were perfected gradually as the tribe increased. … / …[3]

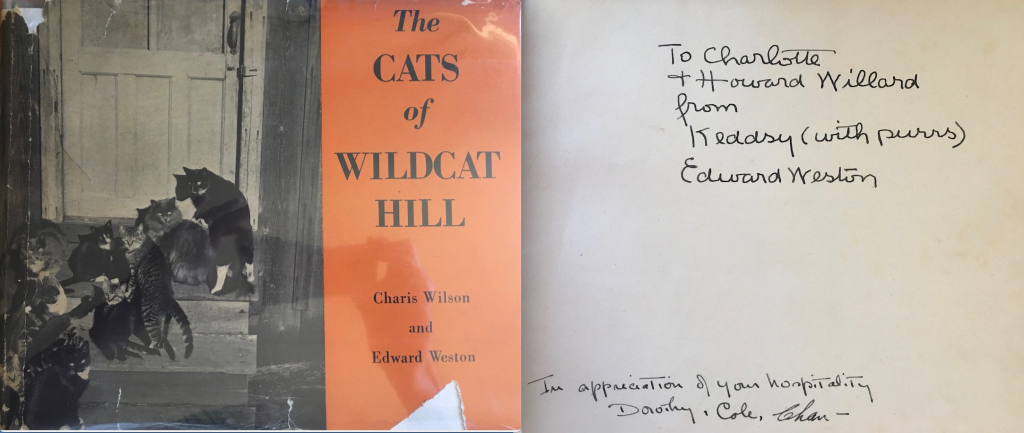

Inscribed by Edward, Dorothy, Cole and Chandler Weston

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

This extravagance of cats was not for the feint of heart. In addition to feeding, nursing, training, and tending to their needs, housing required a bit of creative maneuvering. One amusing architectural solution was the “Franklloydwright Addition,” a ramshackle amalgamation of boxes that successfully satisfied the cats’ homing instincts.[4]

Nor did the colony appeal to everyone. After all, some people are cat fanciers, others most decidedly are not. Even Charis recognized this conflict, noting: “During these years we have had several hundred human visitors at Wildcat Hill, among them all ranks of cat-regarders, from cat-addicts to cat-haters—or, if you wish to be elegant, from ailurophiles to ailurophobes. A few of our guests became sneezy and red of eye, a few became so absorbed in watching the cats they forgot they had come to see us, a few paid the cats no attention whatever—although a dozen cats dispersed around a one-room house are not easy to overlook. …”[5] She also described this perplexing issue with candid aplomb in an article penned for the January 1941 issue of California Arts and Architecture (written in the third person under the pseudonym F.H. Halliday):

… Far from burying themselves in the country, the Westons appear to have set up house on a main travel artery. At least they have a heavier traffic in visitors and sitters than ever found them in Los Angeles. But in spite of that, they manage to go on living in highly uncivilized comfort—working hard, eating when they’re hungry, going to bed when they’re sleepy, enjoying their fantastic family of ten (10) cats. Visitors often shudder delicately and ask “But what do you do with them all?” (Any cat lover knows that’s a silly question, cats being the one animal you don’t have to do anything with.) But to the question “Why so many?” Charis responds by pointing out that if you only have one cat, or even two cats, they belong in the pet class; and, since they associate more with you than cats, they become, to a degree, humanized. But if you have enough of them to form a community (apparently ten is enough) then they develop in relation to each other and remain more catty. However, no one could call the Weston cats spoiled brats. Good manners are mandatory; yelling for food is sternly dealt with, climbing on tables forbidden; all members are taught to shake hands like ladies and gentlemen, and some of them even jump through hoops to show off for company.[6]

Then there is this interesting, independent eye witness account of Wildcat Hill’s dynamic feline environment, as reported in the December 1945 issue of Minicam Photography:

We spent an exhilarating afternoon last summer with Charis and Edward Weston in their cozy home overlooking the broad Pacific near Carmel, California. We came at a time of feverish activity, for Weston was selecting some three hundred prints for his retrospective show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (Feb. 12–March 31, 1946). He had set up an easel under the huge skylight to get a better look at a large selection of prints dating back to 1903. Whenever our eyes wandered away from a print, or him, we saw a cat; always a different one. We simply had to ask why. Yes, he was doing a little experimenting with cats, photographically, that is. How many? Twenty-three, as of that morning. ‘You cannot live with twenty-three cats and not learn something about them—they’re marvelous subjects. I waste more film with them than on landscapes.’ /…[7]

Friends and guests may have greeted the Weston cats with fascination, bemusement and occasional vexation, but when The Cats of Wildcat Hill appeared in 1947 it elicited a flurry of criticism, both pro and con. Prior to the book’s publication, Charis expressed hopes for its success in a letter of 5 May 1946 to Bea and Donald Prendergast: “I didn’t realize till I wrote the date there that today is my birthday! A few more weeks like the last few and I’ll be forgetting my name. The trouble being moving from place to place to place. Anyway I’m here [Los Angeles] for two months and that at the moment represents real security. / I’ve finished the cat book except for a final going over and it will be out in the fall with weston pretty kitty pix and horrid accounts of the behavior of the little dears which I do hope will sell like hot catkins, [typewritten:] there never having been a book like it. /…”[8]

Ultimately, some critics questioned both the wisdom of maintaining an extensive cat colony and the allure of an entire book recounting the triumphs and tribulations of its residents. As one reviewer observed: “Your interest in this book will depend on your interest in reading about other people’s cats—other people’s cats being comparable to other people’s children as topics for sustained discussion. All at once you’ve heard enough and want to go on to something else. …”[9]

Cat enthusiast or not, Weston’s photographs garnered approbation, even if the project itself sometimes failed to please. This review in the February 1948 issue of Minicam Photography covered all bases, from caveat to appreciation:

Few people are neutral on the subject of cats. Generally speaking, one either loves the feline creatures or detests them. Your reaction to this book, which is about nothing but cats, will, therefore, be largely dependent upon whether you are an ailurophile (cat lover) or ailurophobe (cat-hater), and the fact that Edward Weston has made the fine illustrations will probably not make much difference. / Since 1938, when the Westons built their house on the coast of California five miles south of Carmel, they have taken to the cat—not singly, but in droves. Although the population has been somewhat transient, twenty has been a good average number for the furry footpads gracing the Weston household. Charis Wilson, Weston’s ex-wife, with racy good humor and intelligent insight has written a ninety-page chronicle of their comings and goings through the years, and the result, combined with approximately twenty of her husband’s photographs of their pets, makes for mighty amusing and entertaining reading. / The reader whose interest is primarily photography rather than cats may be a trifle disappointed in the illustrations, if for no other reason than their scant number. Most of them are good, and a few are exceptional. Taken with Weston’s famous view camera, they are generally remarkable for their sparkling clarity, sharp rendering of texture, and freshness of approach, which have become to those familiar with his work, a kind of trademark of Weston’s fine photography.[10]

Then there was this lively notice of The Cats of Wildcat Hill proffered by Life magazine in September 1948:

Edward Weston, the famous photographer, is best known for his sharply defined pictures of objects that stand still, like tree trunks, sand dunes and sea shells. Before he got interested in cats he used to feel that even a cow was too active for an ideal camera subject. But when he and his now-divorced wife, Charis Wilson, lived in a cabin in California more than 20 cats lived with them. On rainy days it was a madhouse. Cats had fights in the pantry and kittens in the bureau. Half-wild tomcats yowled outside at night. To the Westons each cat became a fascinating personality. They gave them fanciful names like Bodieson, Zohmah, Gourmy and Elmer Davis, and soon, in spite of himself, Weston started taking wonderful pictures of them. The pictures, some of which are shown here, are now published in a book, The Cats of Wildcat Hill, by Charis Wilson and Edward Weston (Duell, Sloan and Pearce, $3.75).[11]

Finally, if nothing else, Weston’s dedication received applause, as is emphasized in this 4 April 1948 Oakland Tribune review: “… The Weston photographs in this book must be the reward of long and canny patience. Only care, watchfulness and selectivity could bring a result so apparently unstudied, giving us the illusion that we have crossed the frontier and been given the freedom of the cats’ own country. Devotion—not maudlin sentiment, but a devotion that is part scientific, part esthetic, and part a temperamental affinity—is implicit in both photographs and text. / It might almost appear that this young couple built a house near Carmel for the express purpose of having ‘room enough to swing a cat’—or rather, any number of cats. …”[12]

Of course, Edward and Charis’s fascination with cats is hardly out of the ordinary, given the unbroken presence of felines in art, culture and religion that stretches back to ancient times. Nor is The Cats of Wildcat Hill a rare occurrence in the publishing world, although its memoir-like account of feline behavior remains distinctive. So it is not surprising that Weston’s cat photographs began gracing the pages of other publications soon after the book’s appearance. Three contemporary works stand out: Elodie Courter Osborn’s Texture and Pattern: Teaching Portfolio, a portfolio of forty prints published by the Museum of Modern Art in 1949[13]; Bryan Holme’s book Cats and Kittens, published in 1950; and the related Cats Engagement Calendar for 1954. In his “Foreword” to Cats and Kittens, Holme makes the following observation regarding Weston and the other contemporary photographers featured in the book:

On the photographic side, the examples included are by contemporary photographers. The reason, of course, is that only in recent years has photography reached a very high level of sensibility through the skill of a number of men who realize to the full the camera’s potentialities. Edward Weston, for instance, whose photographs have had solo exhibitions in such institutions as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, has been a pioneer for better photography and print making. Two excellent examples by him are shown in Plates LXVIII and LXIX. Other top ranking men in the field who have found cats an interesting subject are Martin Munkacsi (Plates I and XIII), John Rawlings (Plate CXV), Edward Quigley (Plates XIV, XLIV, XLV, LXXVI, CVI), Elizabeth Hibbs (Plates XXIII, CX), Nickolas Muray (Plate XCI), Werner Bischof (Plate XI), Fred G. Korth (Plate IV, VIII), and John Mills, Jr. (Plate CVII). Then there is Ylla, and also W. Suschitzky, two of the greatest animal photographers of the day. Both are well represented throughout the book, and so is Walter Chandoha, who has made cat photography a specialty. / …. / [p. 9:] … To produce real masterpieces like Plates I, LXVIII, LXIX—to give but three instances in this book—requires great sensitivity, a full understanding of the entire photographic process, also endless patience in developing and print making to achieve desired effects. It also, naturally, requires an understanding of composition, lighting, color values when reduced to tones of black and white, and a sure hand at exposing correctly and at the right moment. Dodging, judicious retouching, super-imposing, and other devices employed are all part of the print-making story. The degree to which most or all of these factors are skillfully worked out makes the difference between a good and an indifferent photograph. / …[14]

The exhaustive Cats and Kittens was followed up with a Cats Engagement Calendar for 1954, in which Franklin (Conger 1787/1945) serves as the companion of the week for 4–10 July 1954.[15]

So, why did Weston pour such attention into photographing cats in the early 1940s? His long-standing admiration for them was surely a factor, but much of the concentrated photographic focus likely stemmed from travel and security restrictions imposed during World War II, a period in which even Point Lobos was closed to the public for a time. Largely confined to his home, Weston photographed what was at hand.[16]

Additionally, both Edward and Charis were consumed by wartime responsibilities which left little time for extraneous travel and activities. As Weston wrote to his friends Mona and Felipe Texidor in 1945: “… We have been active in the war effort in ways suited to our life and location. I was air raid warden, Charis drove U.S. Mail. We were both in Air Craft Warning Service; Charis practically ran our local post, and I took a lonely night vigil (because I was lazy mentally, didn’t want to go to school and learn all planes!) We have had a large V[ictory] garden; peas, beans, corn, broccoli, rhubarb, potatoes, tomatoes, chard, asparagus, strawberries, beets, carrots, cauliflower, etc. etc. …[17] The true deciding factor, however, seems to have been Charis, who advocated convincingly for the project and its subsequent book.[18]

Of course, Weston’s fascination with cats—as pets if not artistic subjects—begins much earlier than the 1940s. How far back that interest goes—to childhood?—remains unplumbed, but the earliest reference that this author has identified stems from a Daybook entry on 15 June 1927. In it, Weston reports on receiving two new kittens as a gift from Flora: “… Yesterday, I tried again [to photograph shells]: result, movement! The exposure was 4 1/2 hours, so to repeat was no joy, with all the preoccupation of keeping quiet children and cats,—but I went ahead and await development. / Cats—yes—two orange kittens. Flora brought me: delightful little rascals, but worse than four boys for mischief. / …”[19]

Later that year, on 7 December, Weston mentions acquiring a “magnificent” cat named Pirracas: “I’ve also bought for almost nothing a fine bed spring,—the first real night comfort I’ve had for years,—a sofa, a red chest which Monna painted, and several shelves for books, and Oh, yes, a magnificent cat,—Pirracas. / …”[20] Evidently the magnificent Parracas sired at least one out of a litter of kittens with another Weston cat, the fecund Tonchi.

Clearly, Weston’s delight in feline antics was already in full swing and this enthusiastic Daybook report from 1 June 1928 could easily describe Wildcat Hill in June 1948:

Tonchi’s four kittens are a continuous vaudeville,—comedy, acrobatics and dancing! They furnish free entertainment, more comical, more amazing than any “Orpheum” act. Tonchi seems burdened and bored with maternity: but Pirracas who is papa to at least one of them watches their antics, fascinated. Suddenly, as though the kittens had suggested mice, he pounces upon one,—then what a squealing and skedaddling follows to escape the monster’s jaws. / Prince Pirracas I call him, or Your Satanic Majesty, for in the feline world he must be titled. His aloof elegance, his diabolic moods, his cryptic movements denote Black Magic, suggest allegiance with hobgoblins. / …[21]

Weston’s six cats re-appear as foils to a crowded (and awkward) social gathering in a subsequent Daybook entry of 4 June 1928:

A mess of a party—and my fault. Nahui Olin and Santayo were coming out—it seems I could no longer avoid them! So to prevent boredom I asked Kathleen, which meant inviting her sister for “chaperon”—since K. is in bad with her family—which in turn meant inviting Flora. After all I thought, Flora has not been here to a party since my return,—it may please her. / Then I phoned Schindler to come: he has asked me many times to meet Nahui. Neutra answered the phone, that meant inviting him and his wife,—but I was not sorry for I like them both. / Well when Neutra arrived who should be with him but Sadakichi Hartmann whom I had not seen for a good eight years,—not since I had told him to stay away following an unpleasant episode with Margrethe, which served as a good excuse for I was disgusted enough with his grafting… / Neil and Cole and the six cats squeezed in to add spice. I began to move in circles. … / Flora thanked me on parting. I really think she enjoyed the evening.[22]

(Collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Object Number 86.XA.714.59

© Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona)

These may be among the earliest written references to cats, but what of Weston’s history of actually photographing them? One image, in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, may be the earliest example. It depicts a tabby poised mid-meow in a cat door cut into an adobe wall. Although the photograph itself is undated, it is located in a Weston family album compiled in Tropico between 1908–1914.[23]

In 1921, another cat—of sorts—makes its appearance in a series of portraits of Ricardo Gómez Robelo. Generally titled Poe-Esque, each variation depicts Robelo set against a striking batik created by Robo de Richey[24] titled “The Witch.” Its primary element is a black cat, seen in profile, back arched while raising and licking its right paw.

(Sotheby’s, Photographs, New York, 2 November 1987, Lot 415

© Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona)

More black cats appear in an unpublished photograph from 1932. In it, two rather unkempt examples face off in semi-wary fashion.[25]

A third pre-The Cats of Wildcat Hill print, Cat and Cat Tails from about 1940, appeared in the January 1941 issue of California Arts and Architecture.[26] It depicts Gourmy stretched out on a woven mat, a composition eerily reminiscent of Weston’s Mexican nude of Tina on the Azotea from 1924.

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

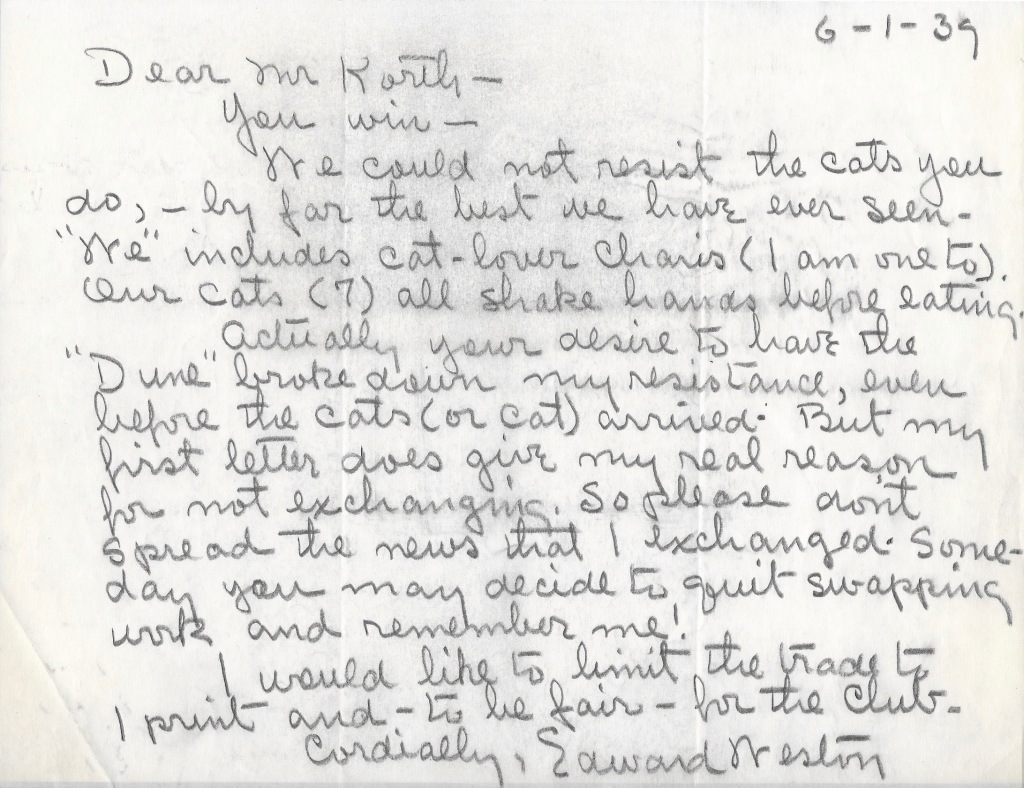

Even when Weston wasn’t photographing cats, he was reporting on the menagerie to his friends in letters that make for informative and entertaining reading. Of particular interest is this 1 June 1939 missive to fellow photographer Fred Korth. In it, Weston appreciatively agrees to exchange one of his “Dune” photographs for one of Korth’s cat images: “Dear Mr. Korth — / You win— / We could not resist the cats you do, — by far the best we have ever seen— “We” includes cat-lover Charis (I am one to [sic]). Our cats (7) all shake hands before eating. / Actually your desire to have the “Dune” broke down my resistance, even before the cats (or cat) arrived. But my first letter does give my real reason for not exchanging. So please don’t spread the news that I exchanged. Someday you may decide to quit swapping work and remember me! / I would like to limit the trade to 1 print and—to be fair—for the club. / Cordially, Edward Weston. / P.S. I hope the print you chose is in good condition; the group as a whole was travel-worn. Glass covers a multitude of sins— E.W.”[27]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.

Weston’s disarming humor shines through in a 1944 letter to Bea and Donald Prendergast where the amusing euphemism “pussygraphs” stands out in an account of wartime activities at Weston’s “old-Carmely-home.” The letter reads:

Wildcat Hill / Bulletin from Weston Front: / A letter from Beandon! [Bea and Don] Glory be — / I have done some good Pussygraphs; not easy with 8 x 10! I make more than 1 neg. to get 1. / Most of my time writing to armed forces. / Cole, Navy—Chicago. / Chan, “ [Navy]—S. Diego. / Brett, Army — N.Y. / Neil, Army Transport Service (Civilian). / Strange that Neil will be first to heave for the “front.” He ships out tomorrow in a 90 ft Tug for (guess) the S. Pacific. / Brett is at last having time of his life going to Photo School in Astoria, living in N.Y. city, receptions, photographing N.Y. / [p. 2:] Jean read your letter before leaving for S.F. After a summer of nothing-but-dripping-fog the sun-shines-bright-on-my-old-Carmely-home. / I have finished Huntington Library Weston collection. / Refused to be rushed on a big 300 print Weston retro. 1902-1945, M. of M. A. so don’t know what will happen. “They” wanted it for March instead of Autumn. / Charis on fire-watch. We do a lot of electioneering—she, house to house & phone to phone. Register, Register, Register. / Your comment on rush job for / [p. 3:] Carnegie very sad. You painted so happily in turgid Tucson. Too many nice people around you? / Here are some more scrappies – – – / And here are large abrazos y besos [two drawn hearts] Eddie / P.S. Last week we had 12 cats / — “ “ [week we] have 23 “ [cats] / —and next “ “ [week we] will have ??? / (Keddsie and Kelly / still expecting).[28]

(Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

Did Edward and Charis ever consider their multitude of cats and kittens burdensome? Yes, indeed. Even the most ardent of ailurophiles have their limits. Over the years the Westons resorted to euthanizing kittens and seriously ill cats as well as soliciting new homes for some members of the colony. In fact, Weston began placing advertisements for his “pussies” in the The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal as early as 1948—a yearly or twice yearly tradition generally timed with the arrival of a fresh litter of kittens—that I have been able to track up through 1954. The first such notice, on 21 May 1948, reads: “FOR SALE: Nine pretty pussies, a penny apiece. To pedigreed people only. Phone Carmel 1317-W for appointment. Edward Weston, State Highway No. 1, at Wild Cat Creek Bridge.”[29]

By the 1950s, the need to winnow out the tribe became more pressing as Edward’s health continued to deteriorate. On 11 August 1950, he placed the following advertisement in The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal: “1 CENT SALE. Buy one kitten at the usual price of 1 cent and get another absolutely free. Better hurry, only three left. Edward Weston, Phone 7-6886, Wild Cat Creek Bridge and Highway 1.”[30]

Evidently The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal found this particular advertisement newsworthy, for it published the following response one week later:

Photographer Edward Weston, who has cats the way other people have ants, needs help. / In the past, whenever his furry tribe threatened to edge him out of his studio at Wildcat Creek, he has put some of them up for sale. He has always refused to give them away—for every departing kitten he has solemnly demanded 1 cent. Usually this thinned things out a bit and everybody was happy. / This transaction has been going on for years, until nearly every cat on the Peninsula can claim some Weston blood. / Last week they began to creep up on him again (about 11, he estimated). Taking a hint from modern merchandising methods, he offered something special in his annual Pine Cone advertisement: two for the price of one. / ‘Buy one kitten at the usual price of 1 cent and get another absolutely free,’ he urged. ‘Better hurry, only three left.’ / ‘Very odd,’ he told The Pine Cone this week, ‘So far I haven’t sold one. Do you suppose Carmel has reached a saturation point?’ / With eight adults and three kittens on hand (or on paw), things looked black indeed. The Weston studio began to look like a Thurber cartoon, with cats clogging every doorway. / Wednesday afternoon the blow fell—five more were born. / The only bright side of the picture is that now they’ll come out even—eight kittens at two for one cent. A lot of people were wondering what he was going to do with that odd one.[31]

Surprisingly, even Paul Outerbridge commented on Weston’s kitty sales in an article extolling the Monterey Peninsula that he wrote and illustrated for Family Circle magazine. The reference to Weston, in a section sub-titled “An Inspiration to Artists,” reads: “… The photographer Edward Weston, famous for the purity of his photographs of this coast line, lives in Carmel Highlands, about four miles below Carmel proper, on the side of the canyon of Wildcat Creek. Collecting stray kittens is his hobby, and once a year he advertises for buyers in a Carmel newspaper. He usually sells these kittens for 1¢ each; last year he offered a bargain—one for a penny and an extra one absolutely free with each purchase.”[32]

Weston’s health may have been diminishing, but his sense of humor certainly remained strong, as evidenced by these two advertisements from 1951 and 1952:

20 April 1951: “FOR SALE—11 kittens at pre-inflation prices (1c each) They are 49% cuter, 22% smarter, 67% prettier (than what?) Ph. E.W. Highway 1, at Wild Cat Creek bridge.”[33]

8 August 1952: “SENSATIONAL PRE-INVENTORY SALE: Nothing like it ever dreamed of before. While they last, 9 kittens at less than 1c each. Phone 7-6886 for an appointment. Edward Weston, Carmel Highlands.”[34]

Have you ever wondered what became of the Wildcat Hill cat tribe after Weston’s death? An article in the Monterey Peninsula Herald suggests an answer that also serves as a fitting coda for this essay.

The late camera artist Edward Weston used to keep flocks of cats around his home at Wildcat Hill in Carmel Highlands. Although mostly of the tame varieties, they were known as the cats of Wildcat Hill. When Weston died recently, just two of the cats were still around. In his will, he left instructions that they should be given good homes, if possible. Otherwise, they should be taken to a veterinarian and put painlessly to sleep. / Weston’s son Neil is still trying to find homes for the cats, both females and both spayed. One is a tabby which Weston gave to the late Hazel Watrous, co-founder of the Bach Festival, when it was a kitten, and inherited back when she died. The other is a gorgeous pale blonde. Both are quite un-wild and affectionate. / If you’d like to give a home to a cat with excellent references, call Neil Weston. MA 4-4664.[35]

(Collection of the Monterey Public Library)

Notes

1 Letter from Edward Weston to Bea and Donald Prendergast, postmarked 20 September 1944; 2 sheets/3 pages; als in ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

2 Roz, “Getting Around the Peninsula: The Cats on Wildcat Hill…” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 33:7 (14 February 1947): 1/Cover. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

3 Charis Wilson and Edward Weston, The Cats of Wildcat Hill, New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, Inc., 1947, “Introduction,” pp. 1–2. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

4 Ibid., p. 2.

In her Introduction to The Cats of Wildcat Hill, Charis wrote: “When the group was large, the matter of housing became increasingly important. From the cardboard cartons we used singly as nurseries, we developed what was known in the family as the Franklloydwright Addition: cartons and boxes set up in series, at angles, in stories. These proved immensely popular with the cats, and reconciled them to remaining outdoors even on foggy and windy days, which is what days often are in this latitude.”

5 Ibid., p. 2.

6 Charis Wilson [F.H. Halliday], “Edward Weston,” California Arts and Architecture 58:1, January 1941, Cover, 11, 16–17, 34–35. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

7 [Hoxie, George R., possibly], “A Swing Around the Country with Edward Weston,” Minicam Photography 9:4, December 1945, 75–83. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

This unattributed article, possibly written by Minicam Editorial Associate George R. Hoxie, is comprised of an introduction (partially quoted above) followed by fourteen illustrations across eight pages. There are no cat photographs among them.

8 Letter from Charis Wilson to Bea and Donald Prendergast, dated 5 May 1946; 2 sheets/2 pp. tl. Envelope postmarked: “LOS ANGELES CALIF. / MAY 6 / 430 PM / 1946.” (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

This letter was clearly written after Charis had left Weston and Wildcat Hill. Her return address reads: “c/o Shea, 6549 Commodore Sloat Dr. / Los Angeles 36, Calif.”

9 Frederick Yeiser, “Book Reviews: Two Books About Cats,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, 6 December 1947, 6B.

Yeiser’s criticism extends to the advisability of rearing cats in the Wildcat Hill; his review reads:

THE CATS OF WILDCAT HILL. By Charis Wilson and Edward Weston. Duell, Sloan and Pearce. $3.75. / Your interest in this book will depend on your interest in reading about other people’s cats—other people’s cats being comparable to other people’s children as topics for sustained discussion. All at once you’ve heard enough and want to go on to something else. / Here instead of assisting at the doings of an ordinary family of cats, you are let in on the history and accomplishments (mostly amatory) of several generations of them. It’s a great deal like reading about such families as the Jukes and the Kallikaks. And the same lessons may be learned. / The Wilson and Weston cat colony in California started quite naturally with one stray unit, presumably pregnant. There were enough yearning sires in the semi-wild group on the hillside to perpetuate the family. In no time at all there were more cats than were needed. / Some of the females were allowed to have two and even three litters a year, which is too many even for a cat. Now it may strike the author as extremely amusing to let cats go on breeding and breeding and bring up their young around her house and she writes in an extremely entertaining manner about them and their habits, but I wonder if cats are merely copy. It seems to me that it’s not quite cricket to make a home for a bunch of cats and then one fine day close the house and go off for a period of 10 months, as the author says she and her husband did (unless I misunderstand her), thus leaving them stranded. / Also, I do not go along with her claim that it is impossible to isolate a female cat that is in season. In fact, I should dispute it. The job requires both patience and careful surveillance, but can be done. Except for these fundamental differences on policy, I found much in ‘The Cats of Wildcat Hill’ to divert me, notably Edward Weston’s engaging photographs. / …

Charis Wilson notes Yeiser’s review in her book, Through Another Lens: My Years with Edward Weston (Charis Wilson and Wendy Madar, New York: North Point Press/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998, p. 331). (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

10 “Book Reviews: The Cats of Wildcat Hill,” Minicam Photography 11:6, February 1948, 128. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

11 “Speaking of Pictures…Famous Photographer Tries His Hand at Cats,” Life 25:10, 6 September 1948, 10–12. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

12 Nancy Barr Mavity, “Books, Art, Music: Cats Made a Boob of Shakespeare, Too,” Oakland Tribune, 4 April 1948, C-5.

13 Elodie Courter Osborn, Texture and Pattern: Teaching Portfolio Number Two, New York: Museum of Modern Art, [1949]. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

The following four Weston photographs are included in Texture and Pattern: Franklin (Conger 1788/1945), Toadstool (Conger 645/1931), Church at Hornitos (Conger 1505/1940), and Tide Pool (Conger 1350/1938).

A Museum of Modern Art Press Release, dated 24 January 1949, describes this Portfolio as follows:

Containing 40 richly printed plates, 11 x 14 inches, in addition to explanatory text, the first of a series of teaching portfolios has just been published by the Museum of Modern Art to be sold at $7.50 per copy. Designed as loose sheets in a slipcase, these portfolios are intended primarily for classroom use by teachers and students in the fine and applied arts. In addition however they will provide a handsome addition to any library. / Prepared by the Circulating Exhibitions Department, four of the series are planned for publication this winter: Modern Sculpture, Texture and Pattern, a portfolio based on the exhibition Timeless Aspects of Modern Art just shown at the Museum and one on industrial design. … / Texture and Pattern, to be issued in the near future, will contain 3 pages of text dealing with the wide variety of patterns and textures and their appeal to the painter, the sculptor, the photographer, the architect. The 40 plates illustrate textures and patterns to be found everywhere around us, such as the texture of a cat’s fur, metal pots, stones, wood and water; the patterns of bridge cables, zebras, stars, lighted windows. These are illustrated in the work of such outstanding photo- [p. 2:] graphers as Edward Weston, Berenice Abbott, Herbert Matter, Barbara Morgan Andreas Feininger; in paintings by Van Gogh, Dali, Klee, Miro, and in sculpture by Arp and Giacometti. / …

14 Bryan Holme, ed., Cats and Kittens, New York and London: The Studio Publications Inc. in Association with Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1950. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

Two Weston photographs included in The Cats of Wildcat Hill are illustrated in Cats and Kittens; they are: Jasmine and Marco Polo (Conger 1736/1944) and Franklin (Conger 1788/1945).

15 Cats Engagement Calendar: Your Day-To-Day Engagements for 1954, New York: The Studio Publications Inc. in Association with Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1953. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

The Weston photograph illustrated in the Cats Engagement Calendar is Franklin.

16 Charis Wilson and Wendy Madar, Through Another Lens My Years with Edward Weston, New York: North Point Press, 1998, p. 329.

As Charis noted in her memoir, “Most of the notes and photographs for the book [The Cats of Wildcat Hill] were made between 1943 and 1945. Maybe because he spent so much time at home during this period, Edward became very involved with the cats and included news of their doings in letters to cat-loving friends.”

17 Letter from Edward Weston to Mona and Felipe Texidor, [1945]; 3 sheets/6 pp.; als in ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

18 Amy Conger, Edward Weston: Photographs from the Collection of the Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona, 1992, p. 40.

Conger writes: “Starting in January 1944 he saved eighty-two negatives of cats that he took that year and another fifty-seven in 1945. There were none from 1943 or from 1946. / The project was Charis’s idea; she wanted to write a book about cats. She was interested in observing how cats would behave when they lived in an environment with other cats, as opposed to people, although, of course, they never allowed the cats to do this. / Edward wrote his sister May about the new project: “Am all set to start a new epoch in my photo-life—emphasis on cats—also Charis will start writing about cats—our cats—should be a best seller. No fancy cats allowed, just plain ‘alley cats.’ 246 Edward told Minor White, “I started photographing cats because Charis goosed me on; I certainly didn’t use them in any symbolic way.”

19 Edward Weston, The Daybooks of Edward Weston, Vol. 2, California, ed. Nancy Newhall, Millerton, New York: An Aperture Book, 1973, 28.

20 Ibid., p. 41.

Conger notes that, upon his return from Mexico, Weston “… set up in his old studio again on Brand Boulevard in Glendale. He acquired at least four cats by the end of the year and definitively clarified his separation from his wife Flora, for those who had any doubts…” See: Amy Conger, Edward Weston: Photographs from the Collection of the Center for Creative Photography, 19.

21 Ibid., p. 59.

22 Ibid., p. 60.

23 This photograph, in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, is catalogued simply as: “[Cat standing in cat door], n.d.” Measuring 15.6 × 11.2 cm (6 1/8 × 4 7/16 in.), it appears in Album “C” of the Getty’s Weston collection which they annotate as “Rincon Homestead Album: Album “C”, a mixed collection of views, snapshots, interiors, etc., mostly at Tropico, California, a family album of Edward and Flora Weston], American, about 1908–1914.”

24 Christie’s, Photographs, New York, Thursday, April 29, 1999, Sale #HENRY-9150, Lot 150.

The notes for Lot 150, Poe-esque (Portrait of Ricardo Gómez Robelo with “The Witch”) read: “… Richey and Modotti lived the life of artists in a garret, seemingly given to an existence of bohemian elegance when in fact they were struggling financially and living with Richey’s family (op. cit., Lowe, Tina Modotti Photographs, pp. 15-18). It was through Richey that Modotti, in 1920, met Ricardo Gómez Robelo, the subject of the portrait offered here, posed in front of a batik by Richey. …”

25 Sotheby’s, Photographs, New York, Monday, November 2, 1987; Sale #5627-MACGUFFIN, Lot #415.

Sotheby’s describes this photograph as “mounted, signed and dated by the photographer in pencil on the mount, 1932; 3 5/8 x 4 5/8 inches.”

26 Charis Wilson [F.H. Halliday], “Edward Weston,” California Arts and Architecture 58:1, January 1941, Cover, 11, 16–17, 34–35. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

27 Letter from Edward Weston to Fred Korth, dated 1 June 1939; 2 sheets/1 1/2 pages; als in pencil. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

Weston followed up with Korth again in a postcard dated 10 June: “Dear Mr. Korth—The Cat came—a beautiful example of real photography. Charis claims it for her room. / We thank you— / Yrs / Edward Weston”

Edward Weston to Fred Korth, postmarked “Jun 10 8:30 PM 1939”; Postcard; als in pencil. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

28 Letter from Edward Weston to Bea and Donald Prendergast, 20 September 1944; 2 sheets/3 pp.; als in ink. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

29 [Advertisement] Edward Weston, “Miscellaneous: For Sale: Nine pretty pussies, a penny apiece. …,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 34:21, 21 May 1948, 19.

The identical advertisement also appeared in the 4 June 1948 issue of The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal.

30 [Advertisement] Edward Weston, “Miscellaneous: 1 Cent Sale. Buy one kitten at the usual price of 1 cent and get another absolutely free…,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 36:32, 11 August 1950, 15.

This advertisement ran in every subsequent issue of The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal through 22 December 1950.

31 “Opportunity! Two Weston Cats For The Price Of One,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 36:33, 18 August 1950, 1/cover.

32 Paul Outerbridge, “A Place Apart,” Family Circle 38:2, February 1951, 26-29, 82-86.

Ironically, the cover of this issue is illustrated with a color photograph by Ted Koepper depicting four Siamese cat kittens in a basket. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.)

33 [Advertisement] Edward Weston, “Miscellaneous: FOR SALE—11 kittens at pre-inflation prices (1c each)…,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 37:16, 20 April 1951, 18.

34 [Advertisement] Edward Weston, “Miscellaneous: Sensational Pre-Inventory Sale…,” The Carmel Pine Cone-Cymbal 38:32, 8 August 1952, 12.

35 Prof. Toro, “Peninsula Parade: Un-wild Cats,” Monterey Peninsula Herald, 3 February 1958, Sec. 2, p. 13.

(Collection of the Monterey Public Library)

Extremely well done, Paula! I’ve always been fascinated with Weston’s obsession with cats, and you’ve really mined the archives for details and insights that have long been missing from the context of this work. I congratulate you on this intriguing and ultimately very satisfying look into the lives of Edward and Charis.

LikeLike

Wow, Tim… I’m positively glowing from your appreciative response. Thank you! I’m so glad you found the essay insightful.

LikeLike

Now I understand why Paul told me once : « we are looking for cats photographs » What a research. Bravo Paula. Gérôme

>

LikeLike

Merci, Gérôme!

LikeLike